Early in the new year, returning home from the office one evening, I picked up a story by the Argentinean writer Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell. The opening pages of “An Eye in the Throat” place us in the thrall of an escalating family emergency, one that might belong to a work of autofiction. But in time, the nature of the story’s reality transforms. On finishing—I had to unclench my jaw and pour myself a drink—I realized that the narrative, like a tormenting Magic Eye, could be read in at least two distinct, and equally haunting, ways.

Like Schweblin’s story, several of the works in this issue seem to disclose, as if by optical illusion, a previously hidden plane of reality. Joy Williams gives us Azrael, the angel of death, who mourns the limited possibilities for the transmigration of souls as a result of biodiversity loss. In “Derrida in Lahore” by the French-born writer Julien Columeau, translated from the Urdu by Sana R. Chaudhry, an aspiring scholar studying in Lahore, Pakistan, is introduced to Derrida’s Glas (“You must read this,” his professor tells him, “it has fire inside it. Fire!”) and becomes a deconstructionist zealot. And in Eliot Weinberger’s “The Ceaseless Murmuring of Innumerable Bees,” bees become variously the symbols of socialism and constitutional monarchy, good luck and witchcraft, war and peace, and much else besides.

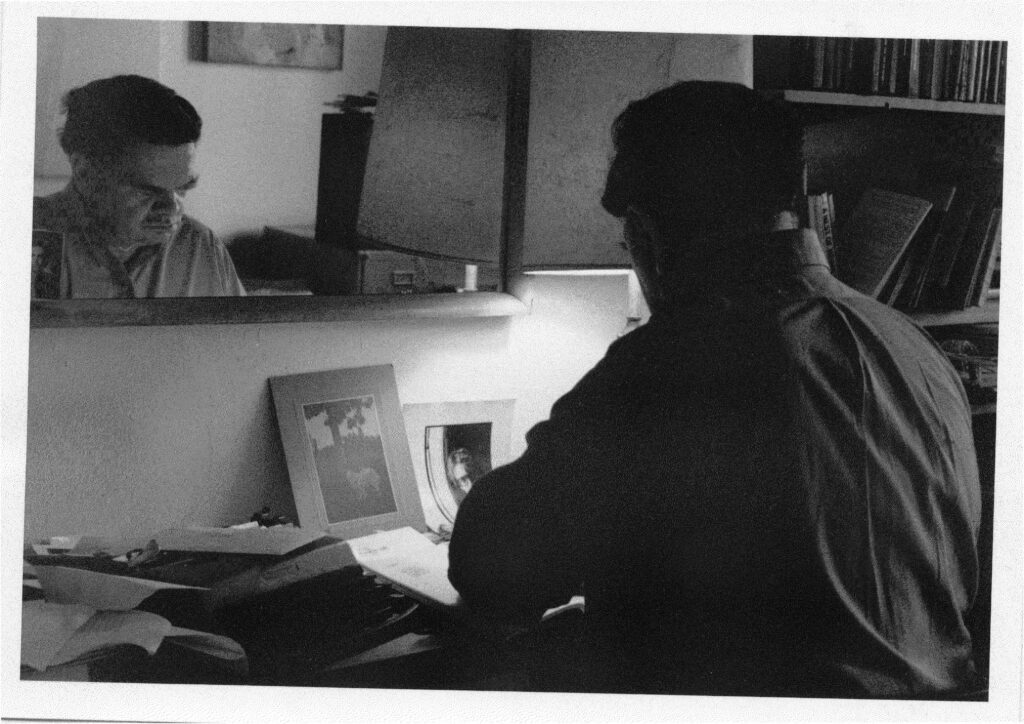

The subjects of our Writers at Work interviews, too, slip between worlds. Jhumpa Lahiri, in her Art of Fiction interview, describes “the woeful treadmill of needing approval” that drove her, at the height of critical and commercial success, to leave her American life behind. “It’s only when I’m writing in Italian that I manage to turn off all those other, judgmental voices, except perhaps my own,” she tells Francesco Pacifico, with whom, in Rome, she spoke in her new language. And in her Art of Poetry interview, Alice Notley describes the need, in her work, to go beyond conscious thought and the “scrounging” of everyday life—beyond, even, the grief of losing loved ones. “You might just freeze, but if you don’t, other worlds open to you,” she tells Hannah Zeavin, before adding, casually, “I started hearing the dead, for example.”

Perhaps a kind of doubleness is fitting for the spring we’re in: the season of hope, which is, this year as ever, filled with dread. When we asked the Swiss artist Nicolas Party to make an artwork for the cover of our new issue, he sent us not one image but two. Like in de Chirico’s The Double Dream of Spring, painted early in the First World War, each image exerts a kind of formal terror, at once seductive and monstrous. We decided that, for the first time in the magazine’s seventy-one-year history, the issue would have twin covers. Subscribers will receive the cover featuring a still life, an array of uncannily sagging apples and pears against rich blue. Buyers at newsstands and bookstores can pick up the version featuring a coastal landscape, albeit one in which the ocean is green and the sky a candy pink. If you’d prefer to alternate between realities, you can always have both.

Copyright

© The Paris Review