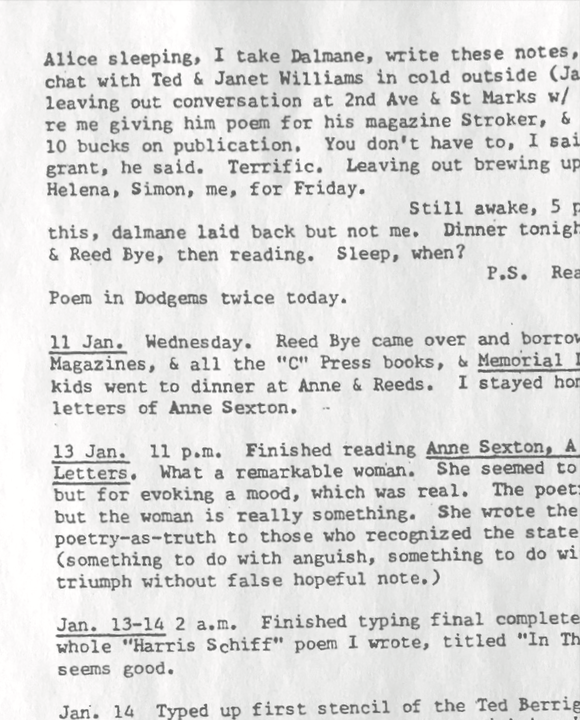

The author’s parents at his grandmother’s home, celebrating their engagement. (All photographs and videos courtesy of Menachem Kaiser.)

A couple of years ago, I sent my parents a chapter from the manuscript of a memoir I’d written. I couldn’t not send it, though I waited—partly out of cowardice and partly to prevent them from claiming a bigger editorial role than I could tolerate—until the copyediting stage, when it was too late to make substantive changes. While working on the book I’d been able to suppress any anxiety over what my family might think or feel about it, but once it was finished I remembered (you really do forget) that those it describes are not merely characters in a story but people in my life. And then, suddenly, everything I’d written about them was available for preorder.

The memoir, which sprang from my attempt to reclaim property owned by my great-grandfather in Poland, was hardly a lurid tell-all. On the contrary: it was polite, restrained. The chapter in question was really the only one I felt nervous about, because in it I mentioned a falling-out and subsequent legal fight among my father and his siblings. On first reading my parents were, as I’d feared, hurt, embarrassed, betrayed, blindsided—but after some difficult conversations, we agreed that I could address their concerns by deleting a couple of sentences, altering a handful of words, and changing the names of my uncle and aunt, a gesture my parents felt would go a long way in demonstrating that my intentions weren’t to harm or disparage. This last request created an unexpected wrinkle—in the event that anyone sued me for libel, I would no longer be able to invoke the standard defense that it was all true—but I was fine with it, and the publisher’s lawyers, given how vague my account of the dispute had now become, eventually gave the go-ahead. So my father’s brother became “Hershel,” his sister became “Leah,” peace was restored, and the knot in my stomach loosened. But a few months later when I received the galleys, my mother read the sensitive section in context and wondered if Leah might after all have preferred to appear under her real name. I said it wasn’t too late to depseudonymize her if that was what she wanted, so my mother called Leah and read her the chapter over the phone.

Leah, my mother reported back, was livid. Beyond annoyed or disappointed—she was furious, hoarse with anger. She doesn’t understand, my mother said, why you even have to publish the book. The problem, it emerged, didn’t have to do with how I’d portrayed Leah, who was barely mentioned—she got a couple of lines of dialogue and no description, as in literally not a single descriptive word—but with how I’d portrayed her mother, Bubby, my grandmother. Or more specifically—because Bubby was also barely in the book—how I’d portrayed Bubby’s sofa, and how that portayal, in turn, implicated Bubby.

What it came down to was a throwaway line, a quip, in a paragraph describing the shiva after Bubby died, in 2005, while the family rift was still very much ongoing. The scene had stayed with me all these years, and I included it in the chapter because it was strange and tragic and funny, and so poignantly captured the tension between the siblings: three adult children, two of them not talking to the third, stuck on the same sofa for a full week as they received well-wishers. To quote the offending paragraph in full: