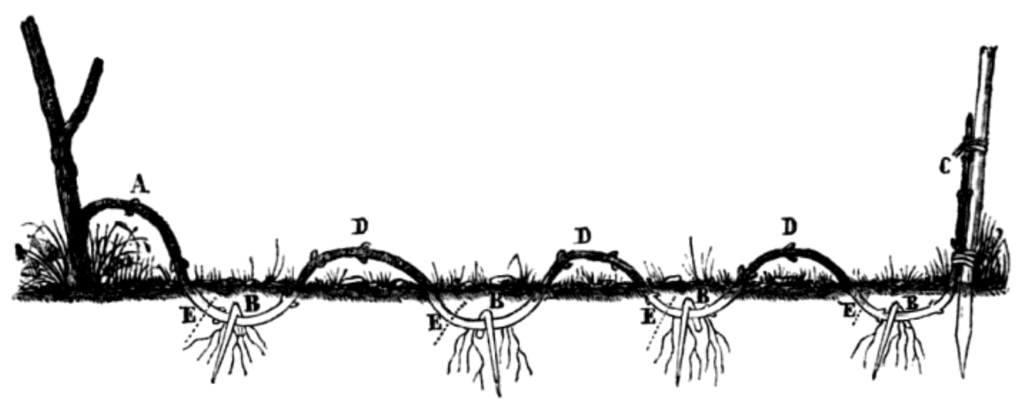

Alphonse du Breuil, Marcottage en serpenteaux, 1846. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Recently, I read Virginia Woolf’s first published novel, The Voyage Out, for the first time. There, I made a discovery: it features a character named Clarissa Dalloway. This encounter initially provoked delight, surprise combined with double take, like bumping into someone I thought I knew well in a setting I never expected to find them, causing a brief mutual repositioning, physically, imaginatively. (Ah! So we’re both here? But if you’re here, where am I?) Then my feelings went strange. For some reason, I felt disgruntled, almost caught out: as if the world had been withholding something important from me. How was I only just now catching up on what—for so many readers—must be old news? Yes, there’s a Clarissa Dalloway in The Voyage Out. She’s married to Mr. Richard Dalloway: the couple have been stranded in Lisbon; they board the boat and the novel in chapter 3. She is a “tall, slight woman” with a habit of holding her head slightly to one side.

I was impressed by the boldness of this move: for Woolf to initiate a character in a minor role and then, years later, to return to her, to open out a whole novel from her private intentions and in this way continue her (Mrs. Dalloway was published a decade later, in 1925). It made me think of E. M. Forster’s two lectures on “character,” published in Aspects of the Novel in 1927. The first is titled “People.” The second: “People (continued).” Then I remembered why I’d had that “caught out,” “I should have known this” feeling: this same technique of novel-growth was also of great interest to Roland Barthes. In his lecture courses at the Collège de France in the late seventies, he named it marcottage.

It’s a horticultural term. A process of plant propagation, working for instance with trees or bushes. It involves bending one of the plant’s higher, flexible branches into the ground and fastening it there, a branch-part under the soil, to give it the time and energy to root. It was also, for Barthes, a method of novel composition, one practiced by Balzac, by Proust. In an article (translated in 2015 by Chris Turner) on the discoveries that initiated Proust’s writing In Search of Lost Time, Barthes defined the method as that “mode of composition by ‘enjambment,’ whereby an insignificant detail given at the beginning of the novel reappears at the end, as though it had grown, germinated, and blossomed.” The detail could be an object, a musical phrase, or the first mention of a character: the point is that it recurs, appearing again in a later volume, connecting several books of a life’s project—only that, each time, it is allocated a different amount of attention, provided with more or less space to develop (to grow). Marcottage. The plant example Barthes reached for to illustrate this in his lectures was the strawberry plant. Strawberries do it spontaneously, “asexually,” sending out long stems called runners from the “main,” or “mother,” plant. The runner touches the soil a small distance away, takes root there, and produces a new “daughter” plant. Together, the plants form a pair, eventually a network of mature plants, making it hard to distinguish daughters from mothers. The generative paths run backward as well as forward.

Marcottage could be a possible metaphor for translation. This work of provoking what plants, and perhaps also books, already know how to do, what in fact they most deeply want to do: actively creating the conditions for a new plant to root at some distance from the original, and there live separately: a “daughter-work” robust enough in its new context to throw out runners of its own, in unexpected directions, causing the network of interrelations to grow and complexify.