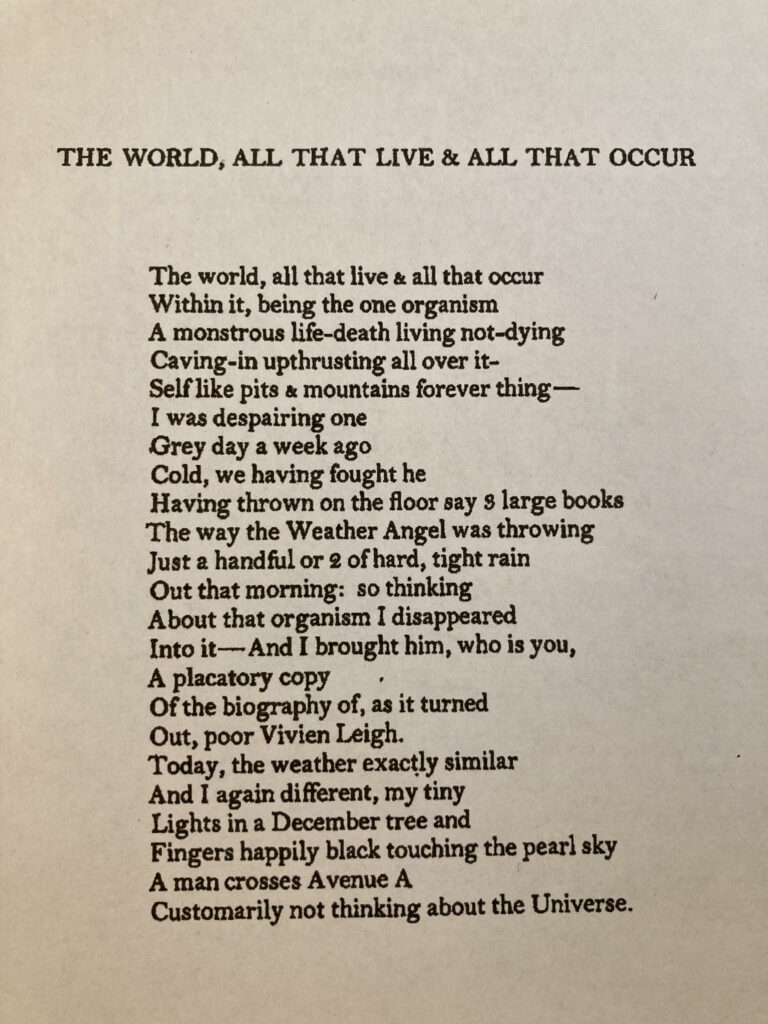

Poem by Alice Notley, in the collection Grave of Light. Courtesy of Wesleyan University Press. Photograph by Sara Nicholson.

Poets have always known how inadequate language is. The speaker of this poem knows it well. No matter how hard she tries to capture the sublime or primordial essence of being, words fail her. Alice Notley herself has written about this in an essay, first published in 1998, called “The Poetics of Disobedience”: “I feel ambivalent about words, I know they don’t work, I know they aren’t it. I don’t in the least feel that everything is language.” Her poem “The World, All That Live & All That Occur” rubs up against the edge of the unsayable. Notice that it begins with “the world” and ends with “the Universe,” that its very structure points to the poem’s origin in and return to an infinite space beyond language. Paradoxically, impossibly, the poem is bounded by boundlessness.

The poem’s situation is simple. A woman is looking out a window on a rainy day in New York City, 1977. She remembers a fight from the week before. She watches a man cross the street. She is also contemplating the nature of being, what she calls “the one organism.” This is how she defines it: “A monstrous life-death living not-dying / Caving-in upthrusting all over it- / Self like pits & mountains forever thing.” She’s speaking fast. These lines have a powerful rhythmic velocity. As she struggles to articulate an ontology, the words get squished together into a hilarious pileup of modifiers. It’s funny, awkward. She knows her definition is inadequate, but it’s the best she’s got.

Between the world and the universe, a woman is thinking. Unlike the man in the street—and I think gender is important here, echoing back to the earlier “he”—she is thinking about it. At its heart, this poem describes a compressed moment in time, put into stark relief by her contemplation of the great organism of being. The moment contains a droplet of eternity; Avenue A is metonymic for “the Universe.” I hear an echo of William Blake’s infinite grain of sand, in which we see writ minutely a whole world.

The poem is full of contrasts. A wife and a husband. The thinking woman in the window, the unthinking man in the street. Men, who are bestial (they don’t think, and they throw stuff), versus women, who are philosophical. The “3 large books” parallel the “handful or 2 of hard, tight rain.” Books, which serve as both a symbol of their fight and their source of reconciliation. The organism, which is all contradiction: its “life-death” shoots up and plunges down at the same time. The word all in the title and first line, which functions as both a singular and plural noun. The word itself, broken into “it-” and “Self,” self and world. She describes the weather as gray when she’d been in despair, but today “happily” as pearl. The poem’s palette is all contrasting brights and darks. Tiny lights twinkling in a Christmas tree, her chiaroscuroed hand against a luminous sky.

Copyright

© The Paris Review