Between the World and the Universe, a Woman Is Thinking

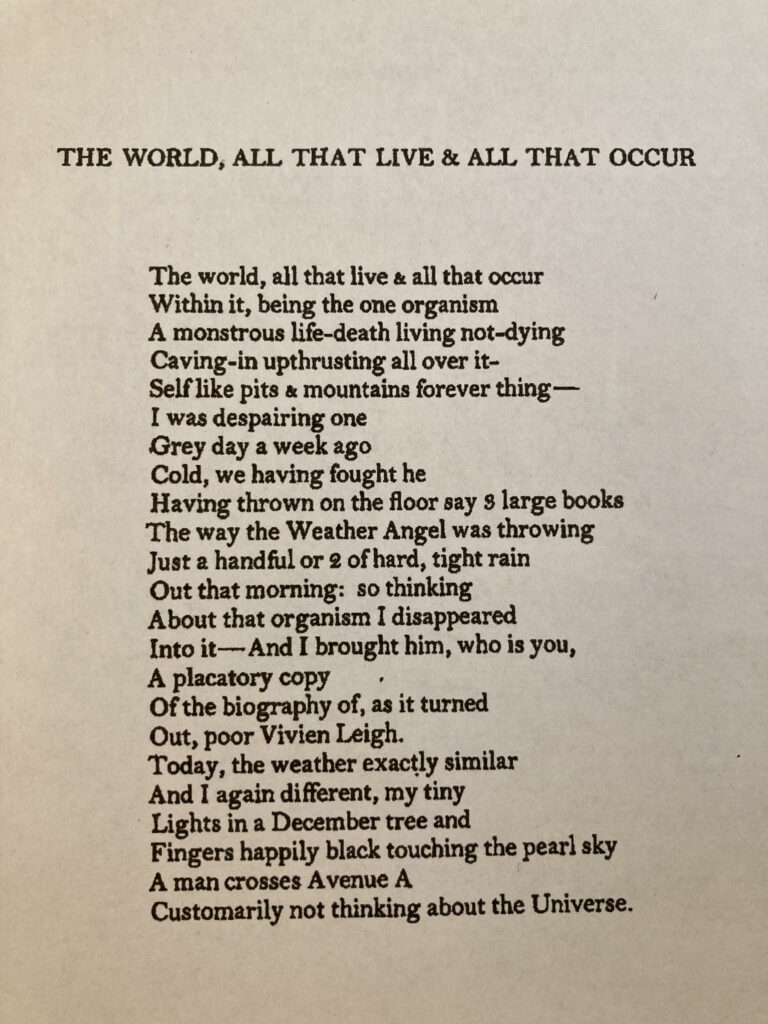

Poem by Alice Notley, in the collection Grave of Light. Courtesy of Wesleyan University Press. Photograph by Sara Nicholson.

Poets have always known how inadequate language is. The speaker of this poem knows it well. No matter how hard she tries to capture the sublime or primordial essence of being, words fail her. Alice Notley herself has written about this in an essay, first published in 1998, called “The Poetics of Disobedience”: “I feel ambivalent about words, I know they don’t work, I know they aren’t it. I don’t in the least feel that everything is language.” Her poem “The World, All That Live & All That Occur” rubs up against the edge of the unsayable. Notice that it begins with “the world” and ends with “the Universe,” that its very structure points to the poem’s origin in and return to an infinite space beyond language. Paradoxically, impossibly, the poem is bounded by boundlessness.

The poem’s situation is simple. A woman is looking out a window on a rainy day in New York City, 1977. She remembers a fight from the week before. She watches a man cross the street. She is also contemplating the nature of being, what she calls “the one organism.” This is how she defines it: “A monstrous life-death living not-dying / Caving-in upthrusting all over it- / Self like pits & mountains forever thing.” She’s speaking fast. These lines have a powerful rhythmic velocity. As she struggles to articulate an ontology, the words get squished together into a hilarious pileup of modifiers. It’s funny, awkward. She knows her definition is inadequate, but it’s the best she’s got.

Between the world and the universe, a woman is thinking. Unlike the man in the street—and I think gender is important here, echoing back to the earlier “he”—she is thinking about it. At its heart, this poem describes a compressed moment in time, put into stark relief by her contemplation of the great organism of being. The moment contains a droplet of eternity; Avenue A is metonymic for “the Universe.” I hear an echo of William Blake’s infinite grain of sand, in which we see writ minutely a whole world.

The poem is full of contrasts. A wife and a husband. The thinking woman in the window, the unthinking man in the street. Men, who are bestial (they don’t think, and they throw stuff), versus women, who are philosophical. The “3 large books” parallel the “handful or 2 of hard, tight rain.” Books, which serve as both a symbol of their fight and their source of reconciliation. The organism, which is all contradiction: its “life-death” shoots up and plunges down at the same time. The word all in the title and first line, which functions as both a singular and plural noun. The word itself, broken into “it-” and “Self,” self and world. She describes the weather as gray when she’d been in despair, but today “happily” as pearl. The poem’s palette is all contrasting brights and darks. Tiny lights twinkling in a Christmas tree, her chiaroscuroed hand against a luminous sky.

I’ve always found this last image difficult to talk about. Maybe it’s the word touching, the fact that she tells us her fingers are literally touching the sky. She is merging with the organism, and the window has become a portal between her everyday life and a universal consciousness beyond. Or is it the odd word order—“fingers happily black touching” instead of “black fingers happily touching”—that so arrests me here. It takes my breath away. Something is happening at the poem’s atomic level. For Notley, poems enact a “vibratory setting-off” of language, a quantum field of movement, transformation, and condensed power. “It can’t be taught and can barely be discussed,” she writes. “It’s maybe like, instead of describing an object, making you hear its atoms spin.”

Notley is a difficult poet. First there’s the sheer volume of her work, nearly fifty books and chapbooks across six decades. Some of these are short, but others—Alma, or the Dead Women; Benediction; and The Speak Angel Series—are sprawling epics, hundreds of pages long each. Much of her work, especially post-2000, is not especially excerptible or anthologizable. She has discussed widely her interest in dreams, telepathy, trance states, and communication with the dead, from whom she takes dictation regularly. “I think most of my poems may be already written,” she says in her most recent book, Being Reflected Upon. These unwritten works are carved onto “a stele or slab” inside “a vast green ‘room’ / with no walls floor or edges” that she visits in dreams. She refuses to fall back on what others have said, to settle into a single mode or style—she is as suspicious of received ideas as Descartes—and the result is a furious integrity (“One must disobey everyone else in order to see at all,” she writes in “The Poetics of Disobedience”). Yet for all this, I find that many of her most difficult poems are short and unassuming, like this one. Inexhaustible. Poems whose atoms, magically, I can hear spin.

I love this poem because it is beautiful. But it’s also personal: I like reading about women thinking. Women like Isabel Archer and Anna Wulf, like the unnamed narrators of Ingeborg Bachmann’s Malina and Clarice Lispector’s Água Viva and Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19. I’m also a woman who likes to brood in windows. Where I live when I live in New York, there’s a window seat that looks out onto the entrance to a neighborhood park. It’s a powerful place to be anonymous. And as Notley’s speaker knows, it’s a good place to think. I like to think of her at the window of her then-apartment at 101 St. Mark’s Place, like a Weather Angel, perched from on high. She’s become a kind of goddess, dreaming the world into being. Dreams that, like so many great poems, are, according to Notley, “messy, embarrassing, truthful, sometimes clairvoyant.” Like this poem, “full of exquisite release.”

Sara Nicholson is the author of three books of poems, most recently April.

Copyright

© The Paris Review