If you’re looking for an anti-censorship group to get involved with, you’re in luck. There are dozens across the country, with more popping up all of the time. While there is certainly a need for a national push against censorship — we need politicians at the federal level to do something — work at the ground level in one’s own community is essential. Find below a roundup of anti-censorship groups who shared their information via this survey in early January. This information has been dropped into a Google Sheet, which you can save a copy of and use as you see fit.

This is, by nature, an incomplete roundup. It includes only the groups who shared their information on the survey. If you know of other groups, feel free to continue utilizing the link above to share information about them. In addition to developing this database of groups, those who share information about their work are given access to a suite of tools and resources to help in the work, thanks to our friends at EveryLibrary. Note, too, that not all of these groups focus solely on anti-censorship efforts; some are also focused more broadly on student rights and education but have anti-censorship as part of their mission and work. Not all groups have web or social media presence quite yet, but keep an eye out.

When you talk about grassroots efforts, look to the groups below. These are not funded by political groups or organizations and are not in the pockets of politicians. If you are in the position to get involved, do so; if you can’t, these are some places where you can also donate money to help the cause.

National Level

Comic Book Legal Defense FundFor the People: A Leftist Library Project (More details coming soon)

Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)Red Wine and BlueStop Moms for “Liberty”Arkansas

No Book Bans Coalition (Bentonville)

Florida

Citizens for Truth and Justice in Education (Central FL)

Clay County Reading AllianceFlorida Freedom to Read ProjectFoundation 451 (Brevard County)

Volusia Fight for the FirstIdaho

Idaho First Amendment Defense GroupSociety of Secret Library FriendsIllinois

Illinois Right to ReadLibrary_defenseProtect Our Library (Lincolnwood)

Indiana

Hamilton County Against Censorship (Fishers and Noblesville)

Iowa

Annie’s Foundation (Johnston)

Kansas

Kansas Against Banned BooksSt. Marys Library Alliance (St. Marys)

Louisiana

Lafayette Citizens Against CensorshipLivingston Parish Library AllianceSt Tammany Library AllianceMaine

Maine Library AssociationMassachusetts

Mass Right to ReadMichigan

MI Right to ReadMissouri

Uturn in Education (Nixa)

New Jersey

NJASL/NJLA Regional Response TeamNew York

No Book Bans Coalition (Brooklyn)

PEN America Prison and Justice Writing ProgramNorth Carolina

Guilford CountyNorth Dakota

North Dakota First Amendment Defense GroupSouth Carolina

Freedom in Libraries Advocacy Group (FLAG) (Greenville)

Freedom to Read SCSouth Carolina Association of School LibrariansTennessee

Right to Read Sumner (Sumner County)

Texas

Access Education RRISD (Round Rock)

Children’s Defense Fund of TexasFREDom FightersGalveston County Library AllianceKISD Equity 4 All (Katy)

Mosaic Community Library (Austin and Travis County)

No Book Bans Coalition (Houston)

Stand Up for Tomball ISD (Tomball)

Texans for the Right to ReadUtah

Let Utah ReadVirginia

Loudoun4all (Loudoun)

Wisconsin

No Book Bans Coalition (Sheboygan)

Don’t see an organization near you? Use this guide to build your own local anti-censorship group.

Book Censorship News: March 10, 2023

Over 90 books have been pulled from shelves in Martin County, Florida, schools “for review.”

You already know this is censorship and you already know it’s Moms for Liberty behind it. “Requiring book vendors to ‘rate’ titles with sexual content before selling them to school districts will be a priority for the Texas House, Speaker Dade Phelan announced Tuesday.”

Remember how over 20 people were killed in a shooting in Uvalde last year in the same state? The Keene Memorial Library’s (Nebraska) decision to allow patrons to demand books be moved to other sections of the library

is going to be a nightmare. A must-read about

the way these book bans infiltrate and impact public libraries. This story out of Moon Public Library (Pennsylvania) shows how not bending to demand means the bottom line is impacted (a.k.a. retaliation). Article is, of course, paywalled, but I’ve broken it for you because this should be free.

The state of school board meetings right now in Brevard County (Florida) and elsewhere. Turns out that the banning of The Upside of Unrequited from a Sparta, New Jersey, middle school

came at the behest of a single complainer.

This pastor is using his free time to complain about books at Robeson County schools (North Carolina)…and the paper is giving him space to talk about it. What even in the world? In good news, Sold and Last Night at the Telegraph Club

survived their challenges in Flagler County, Florida.This Book Is Gay

will remain on shelves in Hillsborough County schools (Florida). The

Oklahoma legislative push to ban books from kids AND adults

advances.

Here’s a rundown of the latest Blount County, Tennessee, school board meeting on book banning and restrictions. Wareham schools (Massachusetts) apparently

never had a book challenge policy prior to last month, and now they do. Policies like this should be standard practice; how these policies are followed is key to successfully combatting censorship.

How Drag Storytime has come under fire in Jackson Heights in New York City. It should be interesting to see how Laramie County school board members (Wyoming) figure out

how to define “sexually explicit” in their library policies.

18 books have so far been pulled from Penncrest schools (Pennsylvania), with another 11 currently under review. The Livingstone Parish Library director (Louisiana)

has decided to resign amid all of the book censorship controversy in his library. “This week, the Campbell County Public Library Board will be going over proposed changes to the library’s collection development policy. The suggested revisions were created by a Florida-based attorney affiliated with a national nonprofit organization. […] Liberty Counsel is a nonprofit organization based in Orlando, Florida, that provides free assistance and representation to advance ‘religious freedom, the sanctity of life and the family,’ according to its website.” So this Wyoming school district drafted a policy from a right-wing religious group?

Separation of church and state does not exist.The new policies in Cy-Fair Independent School District (Texas) would restrict YA books to only middle and high schoolers, and any books “beyond” the YA designation would require parental permission.

So that means even classics are inaccessible to teen readers?Pinellas School Board (Florida)

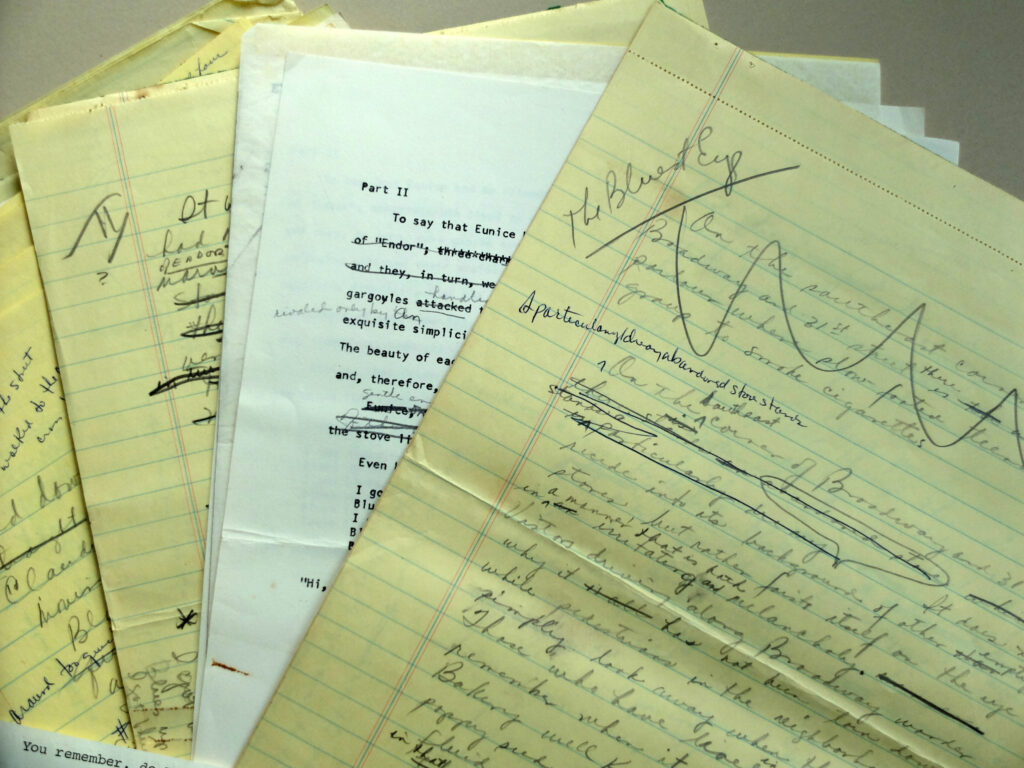

will reconsider its ban on The Bluest Eye over the summer. Again, the proponents of these bills would like you to believe their opponents are perverts. Pedophiles and “groomers” who are titillated at the idea of showing pornography to children. I didn’t see anyone like that among the hundred or so quietly reading demonstrators at the Minot Public Library on Saturday, March 4.”

An excellent piece about the quiet protest against North Dakota book ban bills in Minot. Let’s be clear: by putting this article about how Moms For Liberty behind a paywall, Lancaster’s newspaper is complicit in burying vital information from its community. This story is about Moms attempting to take over the Warwick school board (Pennsylvania), and

I broke the paywall for you. Guess who puts their information out there for free? It’s Moms. It’s real neat how right-wing politicians are actually using children as pawns in their wars. This time, a Kansas republican claimed

a 4th grader’s rainbow drawing was “proof” of indoctrination.Buried in this story is a debate over whether or not Gender Queer

could remain in the Hastings, Minnesota, school libraries.The Faulkner County Library (Arkansas) canceled all of their public programs because bigots don’t understand how programs work,

as seen after their anger over a Drag Queen event. A key part of this story is the director pointing out how much complaining about books there is and yet none of the complainers fill out the complaint forms. And here’s who is pushing to ban books in British Columbia, Canada…

and the group fighting to preserve the right to read. The Duval County Public Schools (FL) supervisor of book reviews has resigned. Perhaps because

her bigoted comments have now come to light? “A Wilson County man in a new lawsuit is accusing the Wilson County Book Review Committee of violating the Tennessee Open Meetings Act, as well as the First Amendment, by holding secret meetings to determine what books could be restricted or banned.”

More of this, please. We all know about the Moms for Liberty list, so that’s not really interesting here. What is interesting is this is the first time

I’ve seen books being challenged in Lonoke County, Arkansas.Greeley-Evans School District (CO) says the classic Beloved

can stay in the high school library. Gender Queer will be able to

remain in Hancock County schools (ME).When you read stories like this one,

you just see how made up this entire book ban crisis really is (Pitt County, NC). A mother puts on a

book crisis performance for the Montgomery County School Board (VA) over Flamer. They aren’t even creative in how they introduce their dramatics. Western Placer Unified School District (CA) listened to book crisis performers over

The Hate U Give being used in 9th grade English classes. The executive director of the Shreve Memorial Library (LA) speaking against book bans and the “parental rights” that

already exist should be a model for others. They keep calling Flamer pornographic which makes clear

they have no idea what pornographic means (Collier County, FL). Regional School Unit 24 (ME)

will keep Gender Queer and Queer in high school libraries.