Around the time he published some of his mostly famous works—Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, and Tropic of Capricorn, to name a few—Henry Miller handwrote and illustrated six known “long intimate book letters” to his friends, including Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Durrell, and Emil Schnellock. Three of these were published during his lifetime; two posthumously; and one, dedicated to a David Forrester Edgar (1907–1979), was unaccounted for, both unpublished and privately held—until recently, when it came into the possession of the New York Public Library.

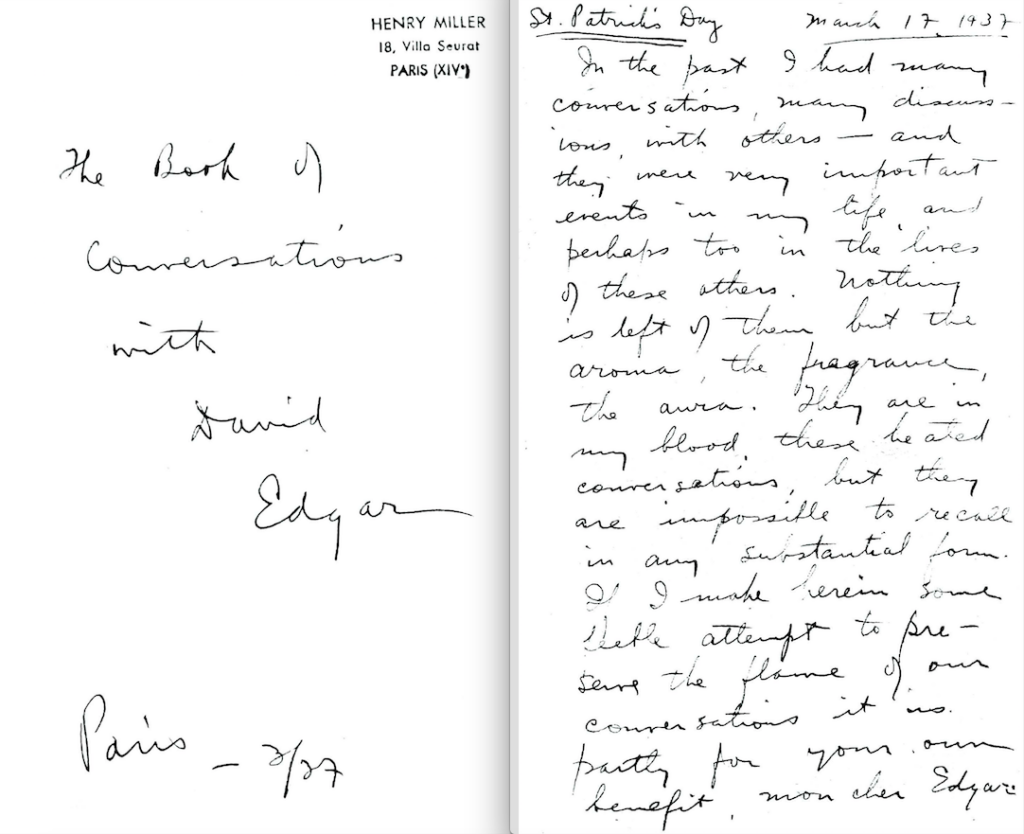

On March 17, 1937, Miller opened a printer’s dummy—a blank mock-up of a book used by printers to test how the final product will look and feel—and penned the first twenty-three pages of a text written expressly to and for a young American expatriate who had “haphazardly led him to explore entirely new avenues of thought,” including “the secrets of the Bhagavad Gita, the occult writings of Mme Blavatsky, the spirit of Zen, and the doctrines of Rudolf Steiner.” He called it The Book of Conversations with David Edgar. Over the next six and a half weeks, Miller added eight more dated entries, as well as two small watercolors and a pen-and-ink sketch. The result was something more than personal correspondence and less than an accomplished narrative work: a hybrid form of literary prose we might call the book-letter. As far as we know, Miller never sought to have the book published, and the only extant copy of the text is the original manuscript now held by the Berg Collection at the NYPL.

Edgar had come to Paris in 1930 or 1931, ostensibly to paint, and probably met Miller sometime during the first half of 1936. At twenty-nine, he was fifteen years Miller’s junior. Edgar soon joined the coterie of writers and artists who congregated around Miller’s studio at 18 villa Seurat. His interest in Zen Buddhism, mysticism, Theosophy, and the occult apparently helped energize Miller to embark on his own spiritual pilgrimage, and to articulate what he discovered there in his writing. “I feel I have never lived on the same level I write from, except with you and now with Edgar,” Miller confided to Anaïs Nin. Miller left Paris in May 1939. Edgar eventually returned to the United States as well. Though the two men seem to have stayed in sporadic contact, they probably never met again. Except for a single letter from Miller to Edgar written in March 1937—a carbon copy of which Miller saved until the end of his life —no correspondence between them is known to have survived.

—Michael Paduano

March 17, 1937

Copyright

© The Paris Review