I like a book with an absolutely wild plot as much as the next person. That’s one of the great things about books, right? They let us experience some truly unbelievable things, like falling in love on Jupiter or exploring a network of ancient sea caves with a snarky robot sidekick. But sometimes it’s nice to read about ordinary stuff. Boring stuff. Everyday stuff. Sometimes it’s not only satisfying, but downright illuminating, and even world-expanding, to read books that celebrate mundanity. Sometimes you just want to read about your life reflected back to you. And sometimes, reading books like that, something magical happens: you realize something about your life or the world; you make connections you would not have made reading a book about space unicorns or climbing Mt. Everest.

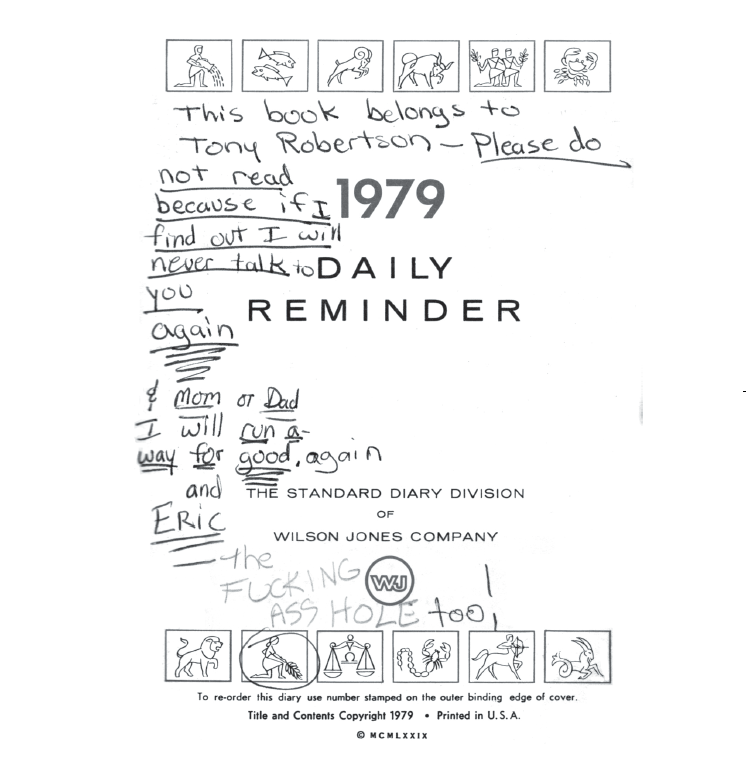

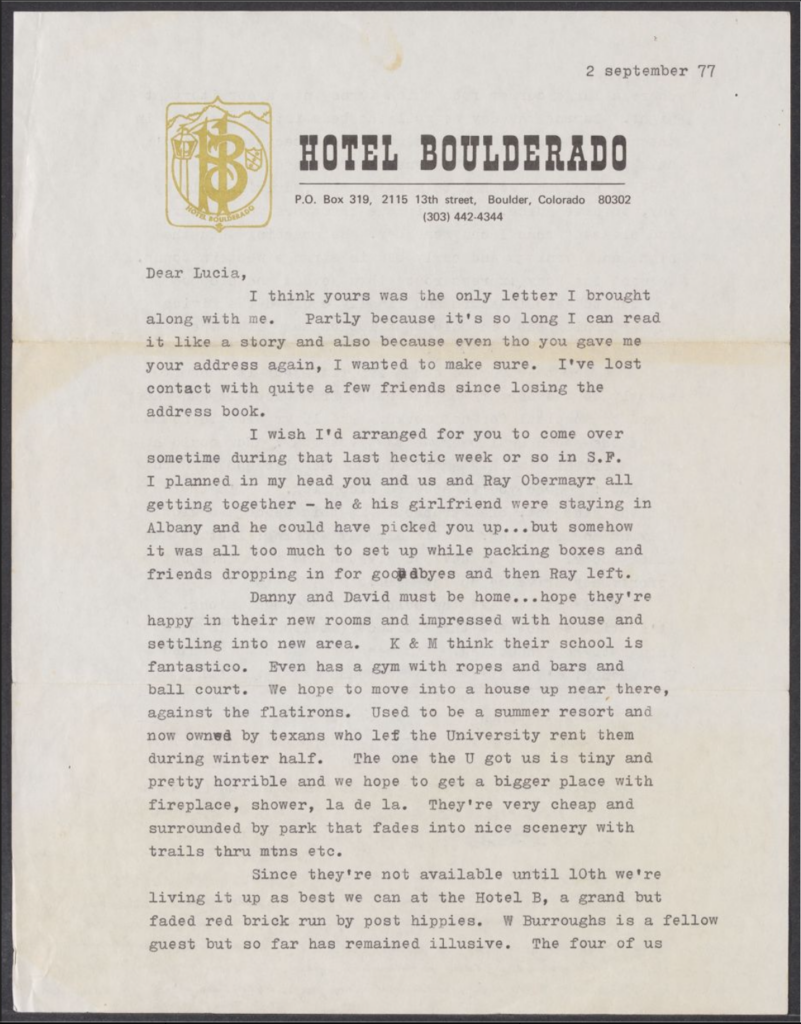

These 10 books — both fiction and nonfiction (and poetry!) — celebrate the everyday. They’re about ordinary things: working in the garden, cooking dinner with your partner, hanging out with friends after a long day. Most of them are not focused on plot, but instead, on the little details that define our lives. There’s a story collection about everyday life in Botswana and one about everyday life in New York City. There are two nonfiction books about diaries and journaling. There’s a novel about sisters that unfolds in a series of breathtaking — and ordinary — scenes.

If you’re looking for adventure, these aren’t the books for you. But if you’re looking for quiet beauty, glorious detail, and books that tell it like it is, you’d better make some space on your TBR.

Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude by Ross GayRoss Gay celebrates the everyday like few other poets I know. In this collection, he writes about gardens and fig trees, compost and cooking, orchards and porch-sitting and music — all the big and little details that make our lives meaningful. It’s a warm and bighearted book, a joyful ode to nature and community. It’s all the more beautiful for Gay’s honesty; he doesn’t ignore the hard, sad truths of the everyday, but weaves these into his poems, too — everyday grief inextricably linked with everyday joy. |

Wash Day Diaries by Jamila Rowser and Robyn SmithThis graphic novel is a collection of interconnected vignettes about four Black best friends and their hair care routines. Each story revolves around a different character, and though the action is centered on/begins with hair care, it doesn’t end there. The stories are about dating, friendship, work, mental health, and more. It’s a joyful, vulnerable, honest book, one of those rare slice-of-life comics that feels perfectly ordinary, but also revelatory. Smith’s artwork is gorgeous — especially the care she takes with the details of all the characters’ different hair, hair care products, and washing routines. |

Copyright

© Book Riot