Divorcée Fiction: On Ursula Parrott

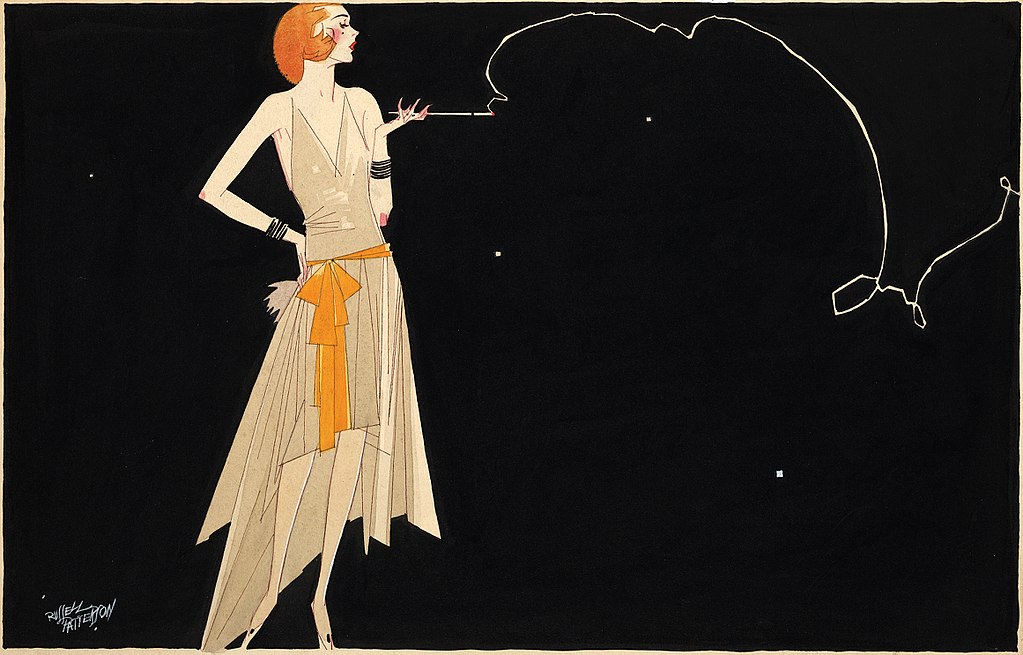

Russell Patterson, “Where there’s smoke there’s fire.” Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I’d never heard of Ursula Parrott when McNally Editions introduced me to Ex-Wife, the author’s 1929 novel about a young woman who suddenly finds herself suspended in the caliginous space between matrimony and divorce. The first thing I wondered was where it had been all my life. Ex-Wife rattles with ghosts and loss and lonely New York apartments, with men who change their minds and change them again, with people and places that assert their permanence by the very fact that they’re gone and they’re never coming back. Originally published anonymously, Ex-Wife stirred immediate controversy for Parrott’s frank depiction of her heroine, Patricia, a woman whose allure does not spare her from desertion after an open marriage proves to be an asymmetrical failure. Embarking on a marathon of alcoholic oblivion and a series of mostly joyless dips into the waters of sexual liberation, Patricia spends the book ricocheting between her fear of an abstract future and her fixation on a past that has been polished, gleaming from memory’s sleight of hand.

It’s been nearly a century since Ex-Wife had its flash of fame (the book sold more than one hundred thousand copies in its first year), and as progress has stripped divorce of its moral opprobrium, it has also swelled the ranks of us ex-wives. Folded in with Patricia’s descriptions of one-night stands and prohibition-busting binges are the kind of hollow distractions relatable to any of us who have ever wanted to forget: she buys clothes she can’t afford; she gets facials and has her hair done; she listens to songs on repeat while wearily wondering why heartache always seems to bookend love. My copy is riddled with exclamation marks and anecdotes that chart my own parallel romantic catastrophes, its paragraphs vandalized with highlighted passages and bracketed phrases. There is a sentence on the book’s first page that I outlined in black ink: “He grew tired of me;” it reads, “hunted about for reasons to justify his weariness; and found them.” The box that I have drawn around these words is a frame, I suppose; the kind that you find around a mirror.

For all its painful familiarity, it’s easy to get caught in the trap of Ex-Wife’s nostalgic charm; there are phonographs and jazz clubs and dresses from Vionnet; there are verboten cocktails and towering new buildings that reach toward a New York skyline so young that it still reveals its stars. If critics once took issue with the book’s treatment of abortion, adultery, and casual sex, contemporary analyses have too often remarked that Patricia’s world cannot help but show us its age. “Scandalous or sensational?” wrote one critic when the book was last reprinted, in 1989. “Times have changed.” Yes and no; released in the decade between two world wars, and just months before Black Tuesday turned boom to bust, Ex-Wife probes the violent uncertainty of a world locked in a perpetual state of becoming.

Lurching toward sexual revolution but still psychologically tethered to Victorian morality, women of Parrott’s generation found themselves caught in the free fall of collapsing convention. The seedy emotional texture of Ex-Wife’s Jazz Age debauchery reflected the panic felt by women across the country who had glimpsed freedom but remained ill-equipped to navigate its consequences. Almost immediately following the book’s publication, the press began a guessing game that sought to identify who was being shielded under its mantle of anonymity; was Ex-Wife a confession, a fantasy, or the indictment of a culture shifting too rapidly to acknowledge the inevitable casualties we leave in the wake of change? By August of 1929, conjecture had correctly zeroed in on Katherine Ursula Parrott (née Towle), a journalist and fashion writer who seemed to bear an uncanny resemblance to her bobbed and brushed heroine.

Considering the book in the context of what we now know about her life, one cannot put much stock in Parrott’s suggestion that Patricia was a composite figure. Instead, Ex-Wife seems to have been a place to record injuries too personal for her to claim as her own. Born in Boston to a physician father and a housewife mother, Parrott decamped to New York’s Greenwich Village shortly following her graduation from Radcliffe College in the early twenties. Her first marriage, to the journalist Lindesay Parrott Sr., ended in divorce in 1926, the year he discovered that the childless marriage he had insisted upon was not so childless after all. In 1924, Ursula had learned that she was pregnant and left the couple’s London home for Boston, where she gave birth to her only son before depositing him in the custody of her father and older sister. It was a secret that she managed to keep from Lindesay and their glamorous circle of friends for an astonishing two years. Marc Parrott, whose afterword concludes this book, would never have a relationship with his father. He was nearly seven years old when his mother finally acknowledged her maternity and assumed responsibility for his care. It was 1931 by then, and Ursula had become one of a handful of women who would find her fortune writing escapist romance tales under the pall of the Great Depression.

Marc Parrott’s recollections of his mother paint a vivid portrait of a spendthrift who often worked for seventy-two-hour stretches in order to meet the deadlines that would keep her (and her lovers) in furs. Parrott swanned through the thirties publishing short stories and serialized novels in women’s magazines, her name often mentioned alongside the Hollywood stars who were attached to her screenplays and cinematic adaptations. Although I never once found her son mentioned in the many news items devoted to her work and her persona, Parrott was occasionally found in the company of a pet poodle improbably named Ex-Wife; in more ways than one, it would seem, her greatest scandal was also her most stalwart companion.

Though Ex-Wife was initially framed as the writer’s endorsement of a dangerous new cultural model, Parrott herself was painfully aware of the double standard that continued to condemn “girls who do.” Divorced for a second time in 1932 and for a third five years after, the writer openly mused about her vulnerability in a world where marriage no longer insulated aging women from “man’s urge for variety.” Parrott called divorced women like her “Leftover Ladies,” a term that implies both surplus and rejection. Her abandoned woman is doomed to a battle that offers neither victory nor surrender. I think of Patricia examining the phantom lines that have begun to etch themselves across her face. I think of her cold creams and her lipsticks, of her awareness of a clock that never stops ticking. “The Leftover Lady is not free to get old,” Parrott wrote the winter after Ex-Wife came out, “for she has entered the competition, in her work and in her social life, with younger women. And that competition is merciless.”

By the early forties, as a serial divorcée who wrote stories with titles like “Love Comes but Once” and “Say Goodbye Again,” Parrott found herself a target of increasing mockery in the press. No longer young or glamorous enough to rate in the world she knew, her name would soon be attached to a series of scandals that could not be dismissed as the product of invention. In December of 1942, she was arrested and charged with helping an imprisoned soldier to escape from the military stockade in Miami Beach where he was being held on suspicion of trafficking narcotics. Michael Neely Bryan was a twenty-six-year-old jazz guitarist who had found some notoriety playing in Benny Goodman’s band before enlisting in the Army; the heady mixture of drugs and sex led to a high-profile 1944 trial and brought a swift conclusion to Parrott’s fourth and final marriage. Under headlines like “Novelist Seen Making Love in Army Stockade,” the writer was described as a matronly woman who, following a lurid encounter, drove through a checkpoint with her lover hidden in the back seat of her car. The two enjoyed one night of freedom at a hotel, where they registered under the name Artie Baker, then turned themselves in to the police, each making a tearful confession. “I looked at him and knew how badly he wanted to go to dinner,” Parrott said. “So I decided to take a chance for him.”

Though Parrott was ultimately acquitted, the trial marked her. No longer welcome in the pages of magazines that catered to “respectable” middle-class women, Parrott published her last story, “Let’s Just Marry,” in 1947, by which time she had completed twenty-two novels, fifty short stories, and four original film scripts, in addition to the eight novels that were adapted for the screen. She would surface in a fresh scandal in 1950, when she was arrested in Delaware after skipping out on a $255.20 bill following a six-month hotel stay. Friends said that she’d gone to Delaware to gather material for a new book, but would note that she’d spent much of her time walking her dog and very little of it in front of her typewriter. Newspapers suggested that she’d been undone by too much success, as though the tale she’d told two decades prior had finally proven to be a cautionary one. Parrott endured one final humiliation that definitively ended her career and any illusion she had of a return. In 1952, she was accused of stealing a thousand dollars’ worth of silverware from a friend who had allowed her to stay in his house under the premise that she needed a place to work on a new book. A warrant was issued for her arrest, and she spent the remaining five years of her life in hiding. She died, at the age of fifty-seven, in a charity ward.

It seems easy from here to understand that Parrott’s career as a writer was usurped by the drama of her scandals. Like many women whose early lives and work are defined by rebellion, Parrott’s indiscretions ceased to appeal once they were no longer deemed youthful ones. Her legacy endured one last condemnation when her work was framed by history as “women’s literature,” a term that was a tombstone in the days before it was understood as an industry. It became a ghost, like its author, neither married nor divorced, resigned to a perpetual now. Drifting around without a future, she drinks and shops, goes on dates, and wonders what else can possibly change in a world that no longer seems to have any rules. “Men used to buy me violets,” Patricia remarks with brutal resignation. “But now they buy me Scotch.”

Maybe I feel protective of Patricia because she feels so familiar to me—like proof that time doesn’t always change us in the ways that we would like to believe. If the book was once too far ahead of its day and later too far behind, it seems now somehow just right, as though we have rounded the circle again and finally found synchronicity. Wedged between Edith Wharton’s constrained society girls and the squandered glamour of Jean Rhys’s doomed wanderers, Ex-Wife was received by an interstitial America still negotiating who and what women were allowed to be. Once caught in a cultural riptide, the book now reads as a shockingly anticipatory account of what it means to want and what it means to be left; we live in a world now where most of us know the feeling of both. I think of the letter Patricia sent to a lover who could not love her back in the way that she needed him to, of the loneliness she felt when day turned to night and back again. “I shall be long dead,” it reads, “of waiting for a telegram saying you are coming home.”

Alissa Bennett’s essays and short fiction have appeared in Vogue, Ursula, and the New York Times. With Lena Dunham, Bennett cohosts the podcast The C-Word, a show that examines and dismantles the mythologies culture erects around public women. She is currently writing a film about the life of Edith Wharton.

From the foreword to Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife, to be reissued by McNally Editions in May.

Copyright

© The Paris Review