A Letter from Henry Miller

Around the time he published some of his mostly famous works—Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, and Tropic of Capricorn, to name a few—Henry Miller handwrote and illustrated six known “long intimate book letters” to his friends, including Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Durrell, and Emil Schnellock. Three of these were published during his lifetime; two posthumously; and one, dedicated to a David Forrester Edgar (1907–1979), was unaccounted for, both unpublished and privately held—until recently, when it came into the possession of the New York Public Library.

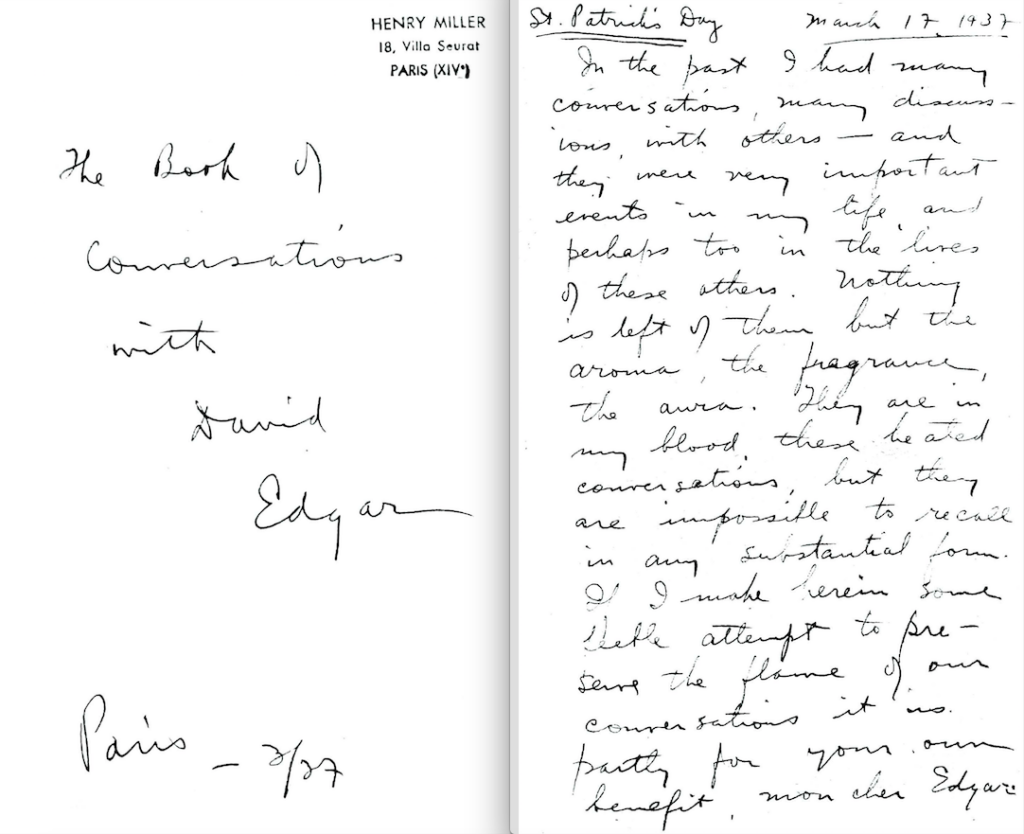

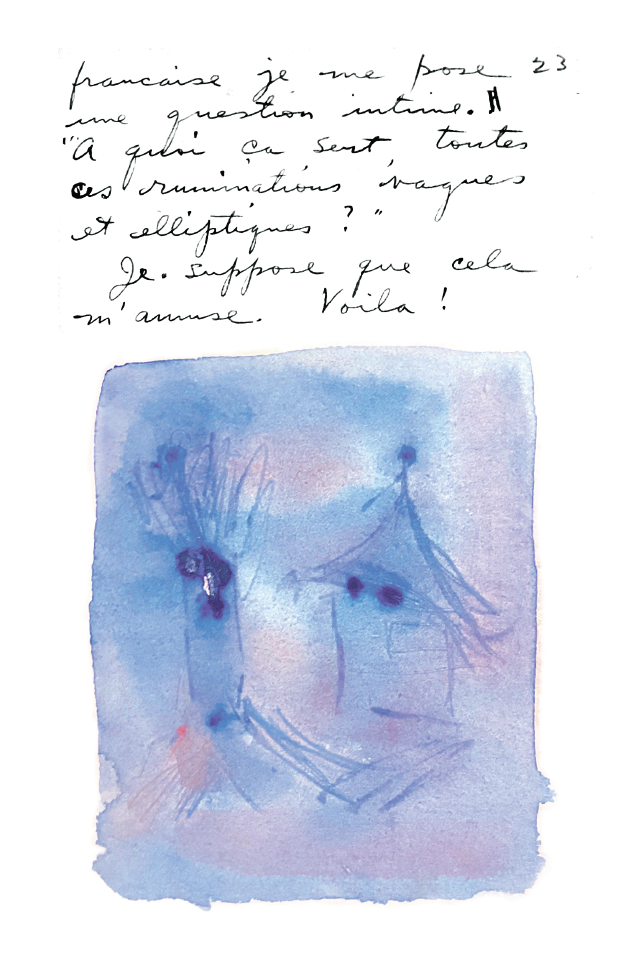

On March 17, 1937, Miller opened a printer’s dummy—a blank mock-up of a book used by printers to test how the final product will look and feel—and penned the first twenty-three pages of a text written expressly to and for a young American expatriate who had “haphazardly led him to explore entirely new avenues of thought,” including “the secrets of the Bhagavad Gita, the occult writings of Mme Blavatsky, the spirit of Zen, and the doctrines of Rudolf Steiner.” He called it The Book of Conversations with David Edgar. Over the next six and a half weeks, Miller added eight more dated entries, as well as two small watercolors and a pen-and-ink sketch. The result was something more than personal correspondence and less than an accomplished narrative work: a hybrid form of literary prose we might call the book-letter. As far as we know, Miller never sought to have the book published, and the only extant copy of the text is the original manuscript now held by the Berg Collection at the NYPL.

Edgar had come to Paris in 1930 or 1931, ostensibly to paint, and probably met Miller sometime during the first half of 1936. At twenty-nine, he was fifteen years Miller’s junior. Edgar soon joined the coterie of writers and artists who congregated around Miller’s studio at 18 villa Seurat. His interest in Zen Buddhism, mysticism, Theosophy, and the occult apparently helped energize Miller to embark on his own spiritual pilgrimage, and to articulate what he discovered there in his writing. “I feel I have never lived on the same level I write from, except with you and now with Edgar,” Miller confided to Anaïs Nin. Miller left Paris in May 1939. Edgar eventually returned to the United States as well. Though the two men seem to have stayed in sporadic contact, they probably never met again. Except for a single letter from Miller to Edgar written in March 1937—a carbon copy of which Miller saved until the end of his life —no correspondence between them is known to have survived.

—Michael Paduano

March 17, 1937

Saint Patrick’s Day

In the past I had many conversations, many discussions, with others—and they were very important events in my life, and perhaps too in the lives of these others. Nothing is left of them but the aroma, the fragrance, the aura. They are in my blood, these heated conversations, but they are impossible to recall in any substantial form. If I make herein some feeble attempt to preserve the flame of our conversations it is partly for your own benefit, mon cher Edgar. I write these notes in anticipation of the day when you will open this little volume and marvel at your own lucidity, your own wisdom.

In talking to you I see always before me a man desperately seeking his own salvation. It is this primarily which has brought me back to you for renewed bouts. For in watching your struggle, in assisting at your salvation, I have taken strength and courage myself. In a way, then, all these conversations in the past, made so vivid now by our recent ones, had the same quality—that of vital exchange. As I listen to you, or even listening to myself, I hear again the themes which only under these auspicious circumstances are brought to light. The eternal themes because the problems are eternal. No, Edgar, make no mistake. We solve nothing. That is, no more than Socrates solved anything, or Goethe in talking with Eckermann. No more than Buddha in communing with himself under the “historic” banyan tree.

We are solving the business of solving! Therein lies an illusion which is not only satisfying, but activating.

I hear you saying often: “No, but freedom is not that at all—it is just the opposite, in fact!”

And as you burst out with it I hear the cogs creaking and the chains slipping. I hear all my other friends in the past speaking with equal conviction, equal ecstasy, in the act of discovery. I believe that in these moments a very real movement, a forward push, is made. It is for these moments solely, whether as contributor or inspired listener, that I come back to the joys of conversation, which it seems to me is an art involving spontaneous creation, or else nothing.

I see you often coming toward me out of the all-enveloping fog of the cloister, with the little notes you so frantically made in your room still clinging to the lapels of your coat. I see you coming toward me full of vital questions.

“Look, I want to ask you something …” My dear Edgar, I know you want to ask me everything. I know that, for the time being, I am playing substitute for God. And if I am giving you back now a reflection of your enthusiasms it is nothing more than the little Bible which you have created in me through the act of revelation.

So many times, in listening to you, I have had the feeling that the word neurosis is a very inadequate one to describe the struggle which you are waging with yourself. “With yourself”—there perhaps is the only link with the process which has been conveniently dubbed a malady. This same malady, looked at in another way, might also be considered a preparatory stage to a “higher” way of life. That is, as the very chemistry of the evolutionary process. In the course of this most interesting disease the conflict of “opposites” is played out to the last ditch. Everything presents itself to the mind in the form of dichotomy. This is not at all strange when one reflects that the awareness of “opposites” is but a means of bringing to consciousness the need for tension, polarity. “God is schizophrenic,” as you so aptly said, only because the mind, whetted to acute understanding by the continuous confrontation of oscillations, finally envisages a resolution of conflict in a necessitous freedom of action in which significance and expression are one. Which is madness, or, if you like, only schizophrenia. The word schizophrenia, to put it better, contains a minimum and a maximum of relation to the thing it defines. It is a counter to sound with …

So where are we? Why at the “Bouquet d’Alesia,” at exactly that segment of the bar which you asked me to examine closely before answering definitively the question about “growth and decay.” In those eighty-five centimeters of the synthetic marble bar God took out his compass and drew a magic circle for us. “The bar is both alive and dead,” He said, in his usual jovial way. “Going toward death as functional concept; vitally alive as atomic compost. Alive-and-dead as bar to man and man to bar. Without extreme unction no birth, no death. Caught at 12:20 midnight in the stagnant flux of introspection … Pose another problem!”

There was a button to be sewed on the sack coat, pockets to be mended, a fire to be made. The answer today before yesterday’s questions still caught in the typewriter roller. What to do? A lait chaud tout seule! [“Just a hot milk!” A more literal translation, which Miller plays on in the following two sentences, would be: “a hot milk all alone!”] Always, when cogitating and recogitating, a lait chaud. Always tout seule when answering the final question which is for tomorrow. What happened? I mean—today? Why tomorrow. A lait chaud! Being God imposes difficulties, godlike ones to be sure. For one thing there is neither Time nor Space. Then again there are no beds, no holes to be mended. Everything moves on casters on a waxed floor. There is no end to the floor—no wall, no exit. It seems to me we are now safely and snugly at home. No, not quite either. The missing blanket is a bit wrinkled at the foot of the missing bed. God is so snugly ensconced that he begins to have imaginary, and of course very very trifling but very very real aches and pains. He is like a sound and healthy man with an amputated leg just before the winter rains set in. He wants a real leg so that he will have an excuse for complaining. Now, as every scientist will tell you, the real leg, of course, is in the brain. That’s why it can hurt even when it’s missing. But God has no arms and legs, neither has he a brain, so the difficulty must lie elsewhere. It lies exactly, if my memory serves me right, a league and a half northeast of Neptune. The only real difficulty here, however, is in distinguishing north from south, and east from west. God knows that Himself, even though he is without a brain, and that, that alone, is the reason why He is troubled.

“Donnez-moi de la monnaie, s’il vous plaît.” [Give me some change, please.]

PLEH—not PLAY.

Home with Expression and Significance … The lucidity of Keyserling is amazing. (The fire could be a little brighter, even if not warmer.) So is it with Krishnamurti. What was that again about Memory—the unlived residue? Or some such thing. (Wonder if that bugger Henry Miller is starting another volume of work.)

No, often Henry Miller is already in bed planning the next day’s adventure. Henry has the faculty of knowing when to call it a day. He says ofttimes, just before falling off to sleep, “if I croak during the night it will be perfectly all right.” Dying peacefully with his boots on. That’s the way Henry takes it. You can do more than just so much each day, but on condition that you lose no time thinking about it.

Just so I make a sort of mental and spiritual progression each time I meet you and we have it out. I learn by your mistakes and am fortified by your discouragement.

You profit then by your friend’s misfortune? Oui, c’est ça! Je ne me blame pas. Content, très content, moi. Tout s’arrange dans la vie pour quiconque sait d’en profiter. Je ne me trompe jamais. Toujours droit et en avant. Avant et après—il n’y a que ça. Bien sure, il y a aussi des hypothèques—c’est à dire, des ennuis. Comme c’est beau, les ennuis! Comme la pluie septentrionale! La terre tourne. Et nous aussi. L’on tourne en place. Chaque minute compte. Chaque minute fait quelque chose irremédiable. C’est bon, ça. Tout juste. La vie se présente à nous en mille aspects. Chaque aspect a son valeur, son moment, pour ainsi dire. Faut en profiter. Il n’y a pas à plaindre. Faut jouir. Faut faire l’amour avec les sacrés moments qui sont vraiment sacrés. C’est tout, mon ami. Absolument tout. Pourtant, il y a quelque chose à ajouter … C’est pourquoi je ne m’arrète pas. Je continue … Je laisse la parole à Dieu. Il sait beau parler. Son métier, quoi! [You profit then by your friend’s misfortune? Yes, that’s right! I don’t hold it against myself. I’m content, very content. Everything in life works out for whoever knows how to enjoy it. I never make a mistake. Always straight and onward. Before and after—that’s all there is. Of course, there are also debts—that is, hassles. But what beautiful hassles! Like septentrional rain. The earth rotates. And so do we. We rotate in place. Each minute counts. Each minute is something irrevocable. It’s good that way. Just right. Life presents itself to us under a thousand aspects. Each aspect has its own value, its moment, so to speak. You have to enjoy it. There’s nothing to complain about. You need to have some bliss. You have to make love with sacred moments which are truly sacred. That’s all there is to it, my friend. That’s absolutely everything. And yet, there is something more to add … That’s why I don’t stop. I keep going … I give the floor to God. He knows how to speak beautifully. It’s his job!]

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” The word was not a noun, or an adjective, or a preposition, or a conjunction (quel horreur!), but it was a Verb. You can see how God must be in the Verb—it’s so perfectly natural, so spontaneous and autochthonous. God does not come home each evening, after a hard day at the factory, and knock out words. Ah no! Pas lui! Il sait mieux faire que ça. [Ah no! Not him! He knows better than to do that.] You see, God doesn’t permit himself to get fatigued. He is awake twenty-four hours of the day, and each day he is becoming more and more wide awake. It’s his nature to be that way. Homer nods now and then—God never! Voila une petite différence très impressionante. Faut pas ignorer cela. [This little difference is very striking. Don’t overlook it.]

Et comment ça se fait que le bon Dieu ne s’endort jamais? [And how is it that the good Lord never falls asleep?]

Parce-qu’il se mefie de tous les mots qui ne sont pas des verbes. De preférence il se sert du “present participle,” comme on dit en anglais. Oui, il n’aime pas beaucoup le passé parfait, ni le subjonctif. Il se dit toujours = en anglais naturellement = “I am doing this … I am doing that … I am having a good time.” Oui, il rigole tout le temps. Il ne sait jamais ce que se sera demain, ni ce que s’est hier. Oui, un drole de type, lui. Il s’en fout toujours. [Because he is suspicious of all words that are not verbs. He prefers to use the present participle, as we say in English. Yes, he doesn’t really like the past perfect, nor the subjunctive. He’s always telling himself = in English, naturally = “I am doing this … I am doing that … I am having a good time.” Yes, he’s always joking. He never knows what it will be tomorrow, nor what it was yesterday. Yes, he’s a funny guy. He never gives a damn.]

Et pourtant, il fait du progrès. Oui, c’est merveilleux ce qu’il a fait dans le temps—sans vouloir rien faire. L’on se demande parfois s’il l’a bien fait pour lui-même, ou pour nous. Moi je crois qu’il a fait tout pour lui-même. Je crois, moi, qu’il est tout à fait narciste. “L’univers, c’est moi!” il se dit toujours. Et il a raison. Parfaitement raison. Il s’y connait, ce type là. [And yet, he makes progress. Yes, it’s marvelous what he’s accomplished in time—without wanting to do anything. One sometimes wonders whether he has done it for himself, or for us. Personally, I think he’s done it all for himself. I think he’s a complete narcissist. “I am the universe!” he’s constantly telling himself. And he’s right. Perfectly right. The guy knows what he’s talking about.]

Mon cher Edgar, tu te connais, toi aussi. Mais, permettez que je vous pose une toute petite question: est-ce que tu t’y connais aussi? C’est une constatation qu’on fait rarement. L’on ne se pose pas des questions pareilles. Mais on a tort. La santé morale n’est rien d’autre que les réponses automatiques à ces question intimes. Donc, pour mettre fin à cette partition francaise je me pose une question intime. “A quoi ça sert, toutes ces ruminations vagues et elliptiques?” [My dear Edgar, you, too, know yourself. But allow me to ask you one little question: do you also know what you’re talking about? It’s an observation that is rarely made. One doesn’t ask oneself such questions. But that’s a mistake. Moral health is nothing other than the automatic responses to these intimate questions. And so, to bring this French partition to a close, I ask myself an intimate question. “What’s the point of all these vague and elliptical ruminations?”]

Je suppose que cela m’amuse. Voila! [I suppose it amuses me. Voilà!]

Edited and translated by Michael Paduano.

From The Book of Conversations with David Edgar, out from Sublunary Editions in May.

Henry Miller (1891–1980) grew up in Brooklyn before eventually moving to Paris. It was there that he made the acquaintances that would bring about the publication of a remarkable run of books, including Tropic of Cancer, Tropic of Capricorn, and Black Spring. Those early books, Tropic of Cancer in particular, drew intense criticism for its sexual candor and explicitness, leading to a landmark obscenity trial when it was finally published in the United States by Grove in 1961. He eventually settled in Big Sur, California, where he continued to write and paint until his death in 1980.

Copyright

© The Paris Review