Marveling Over Closing Poems

Like the excitement surrounding a much-anticipated season finale, closing poems are an occasion, but that’s not to say that I don’t love all the other parts of a poetry collection. In fact, I read books from the title to blurbs, although not always in that order. Fascinated by the “Notes” and “Acknowledgements” sections, I pretty much always read the back matter before finishing the main attraction.

One reason for skipping around: I want the final page, poem, sentence, line, then word of a work to be the last thing I read. I prefer to savor endings, to bask in my feelings. Plus, the last lines of closing poems end a piece and a collection, leaving readers with a sense of clarity and closure and sometimes an opening. So, I guard that space by finishing the endpages beforehand.

In recent years, my interest in poetry has multiplied, especially my curiosity about how everything from a poem to a collection comes together. I peruse poetry chapbooks and collections, craft essays, interviews, and podcasts. While writing this, gratitude for “Ada Limón on How to Write a Poetry Collection” from Literary Hub and Chet’la Sebree’s online course “Exit Strategies: How to End a Poem” via Hedgebrook kept arising. Knowing their invaluable lessons swim in my brain and inform my readings, I celebrate them here.

A devoted rereader and someone rendered speechless and still by choosing favorites, I often look to my rereads to learn and observe what moves me. Because word limits, I utilize that approach in this essay. Now, onto those go-to, heart-grabbing closing poems.

|

Again and again, I reference the constellation of poems taped to my bathroom mirror. Those memorized pieces feel like friends. Even when I’m not revisiting or reciting them, they, similar to the formative books stacked in my writing space, loom in their comforting, inspiring way. The six touchstones include a closing poem, “Object Permanence.” This love poem of love poems ends Ordinary Beast. I’ve read Nicole Sealey’s debut collection exploring family, friendship, mythology, and race five times, but I don’t even know how to begin to describe the number of times I’ve turned to its final poem.

Comprised almost entirely of couplets, “Object Permanence” consists of eight two-line stanzas and begins, “We wake as if surprised the other is still there, / each petting the sheet to be sure.” The ninth and final stanza features a single line: “how I’ll miss you when we’re dead.” While addressing mortality, the ending departs from the poem’s previous form. This change seems sudden, straightforward, and poignantly tragic in its loneliness. And yet, it rings hopeful, romantic, and reassuring. In the concluding line, the speaker hints that love transcends death. And if tears overwhelm your eyes, both the title and corresponding entry for the poem in the “Notes” reminds audiences, “objects continue to exist even when they cannot be observed.”

|

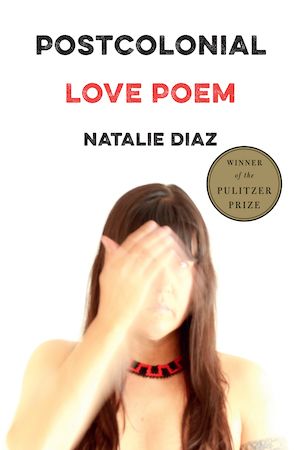

With four reads and counting, I continually seek out Postcolonial Love Poem. Delving into the body, desire, language, and nature, Natalie Diaz’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book keeps popping up in my life, too. Author after author I admire cite it as a book they admire. As I drafted this essay, an earlier version of the closing poem resurfaced in my social media feed, which I, of course, found serendipitous, immediately reread, and left the gleaming window up in my browser to study over the following days.

Glancing at dates and my beloved copy, the first time I read Diaz’s sophomore collection occurred during a time of marginalia. In “Grief Work,” a poem meditating on intimacy and healing and love, I left five hearts and two lines in the margins along with a dog-ear. I hearted and hug close that opening, “Why not now go toward the things I love?” One of the many things about this poem that draws me in, along with the innovative punctuation and use of space, is the movement from I and her and she and my and hers and me to, near the end, we. At the mention of the We, the words go and love return in the line (also hearted): “We go where there is love, // to the river, on our knees beneath the sweet / water….”

|

While thinking about endings, I bookmarked Limón’s “The End of Poetry,” a haunting closer with end in its title, early on. Since summer, I’ve been rereading The Hurting Kind, which is organized into four parts according to season, at the arrival of each equinox and solstice. Three quarters into my third read, I jotted return to “Spring” in my calendar on March 20, but I’ve flipped to the last poem with a fangirl frequency. A lover of lists and repetition, I applaud the sound — “osseous” and “chiaroscuro” and “the long-lost / letter on the dresser” — in this piece, and I delight in surprises.

Like the jolt of poetry-lightning I experience when reading the last line of “Object Permanence,” the last line of Limón’s closing poem calls to me. On the page, it — practically half the length of most lines — draws attention to itself with its brevity. In addition to being three syllables shorter than the second shortest line and eight syllables shorter than the longest line, the final line contains the first and only period in the piece, accentuating a finality after a winded-ness: “I am asking you to touch me.”

May these stunning poems inspire you to spend time with the above collections and the endings of poetry books dear to you. If you find yourself craving more breathtaking closing poems, I sat on a yellow pillow in front of my poetry bookcase over a few wintry mornings to gather a selection of ten:

“Because You Can’t” by K. Iver from Short Film Starring My Beloved’s Red Bronco “I slept when I couldn’t move” by Khadijah Queen from Anodyne “If They Come for Us” by Fatimah Asghar from If They Come for Us “In the Fields” by Jake Skeets from Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers “Long Nights” by Jenny Xie from Eye Level “The moon rose over the bay. I had a lot of feelings.” by Donika Kelly from The Renunciations “Orchard of Unknowing” by Paul Tran from All the Flowers Kneeling “Pandemic Spring” by Shelley Wong from As She Appears “Such Things Require Tenderness” by Luther Hughes from A Shiver in the Leaves “Us & Co.” by Tracy K. Smith from Life on MarsIf you harbor countless crushes on poems or are developing them, please pore over more poetry posts, including this essay’s older sibling by yours truly, Marveling Over Opening Poems; A Guide to U.S. Poet Laureate Ada Limón’s Poems; and our poetry archives.

Copyright

© Book Riot