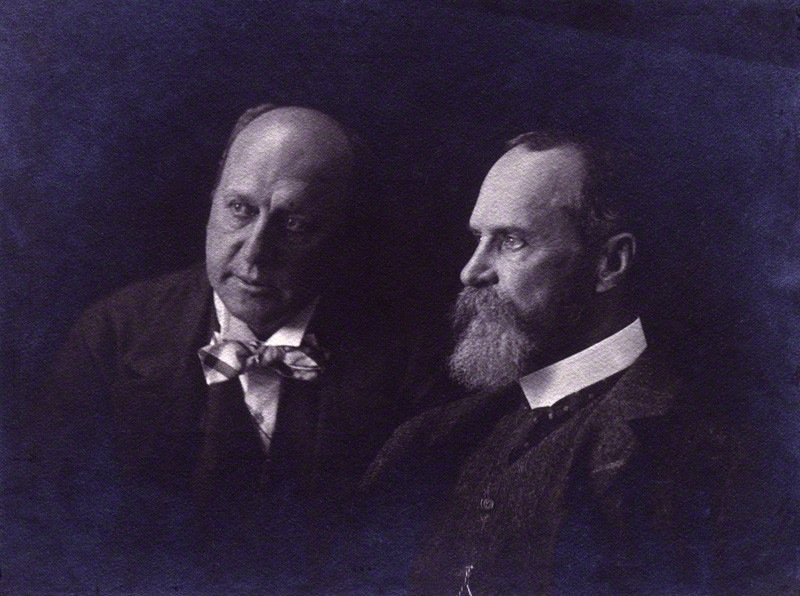

William and Henry James

William and Henry James. Marie Leon, bromide print, early 1900s, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

When Henry James decided to come to America in 1904 and 1905, his elder brother, William James, was not immediately pleased. William said that while his wife, Alice, would welcome his visit (she and Henry had a firm bond), he felt “more keenly a good many of the désagréments to which you inevitably will be subjected, and imagine the sort of physical loathing with which many features of our national life will inspire you.” There follows an account of how traveling Americans ate their boiled eggs, presumably in hotels and on trains, “bro’t to them, broken by a negro, two in a cup, and eaten with butter.” As a source of physical loathing, this seems a bit excessive: one might linger over William’s attempts to keep Henry’s visit at bay. William’s letter seems more to the point when he notes: “The vocalization of our countrymen is really, and not conventionally, so ignobly awful … It is simply incredibly loathsome.”

William’s discouragement provoked from Henry a declaration of his determination not to be deterred from coming. “You are very dissuasive,” he wrote to William. Henry, in a plaintive reply, noted that whereas William had traveled much, he had not been able to—he not been able to afford it nor to leave the demands of producing writing for money. It’s as if Henry must plead for his brother’s approval before he can travel back to his native land. And yet the pleading is accompanied by Henry’s self-assertion, he’s thought it through, analyzed the consequences. There is so often in their dialogues this deference of the younger brother to the elder, mixed with self-assertion, an insistence that the pathetic younger brother does know what he’s doing. I suppose we might, in contemporary psychobabble, call Henry’s relation to William passive-aggressive. William’s to Henry, though, has a tinge of sadism that we will see take more overt forms. His response to Henry’s desire to travel home is a strange mixture of welcome and repulse, a recognition of their sibling bonds along with the sense that they bind annoyingly, that he’d rather not have his brother around.

William’s wife, Alice Gibbens James, was much more openly hospitable to Henry’s announcement of the proposed visit. She and Henry seem always to have had a warm and understanding relationship. William claimed that marrying Alice had “saved” him—from what exactly, it’s hard to specify. He had many bouts of depression as a young man, and it has been suggested that he suffered from a self-punishing guilt about his masturbation. Yet while married to Alice, he managed to be absent often, trekking in the Adirondacks or traveling elsewhere. Henry apparently remarked on what he thought was William’s neglect of his wife; according to William’s biographer, Henry told his Chicago hostess that Alice was “the finest woman living, only criminally sacrificed.” It’s not clear whether this is simply the comment of a man who never married and understands little of the daily negotiations of a long-standing marriage, or if it speaks of a truth about William and Alice’s relationship. Reading Alice’s biography, one is struck both by William’s psychological neediness and by his frequent escapes from home on various trips. It seems odd to us today, for instance, that William managed to absent himself following the birth of each of his children. And, in general, Alice seems to have borne the brunt of all the child care and household management as well as of William’s demands for sex—his absences seem to have been his way of handling birth control—and his volatile temper.

Alice, as Henry was the first to note, married the whole James clan, and took on its vast responsibilities, including assuming the management of Lamb House when Henry fell into his deep clinical depression in 1910, and then tending to him on his deathbed. One gets the impression that Alice alone was able to understand the brothers in ways neither of them alone could understand each other. When Henry set out on his American trip, he announced that he could not stay with people, that he needed the privacy and luxury of a hotel. He made a few exceptions: Minnie Jones in New York; Edith Wharton in New York and Lenox, Massachusetts; Dr. William White in Philadelphia; the Vanderbilts at Biltmore in North Carolina, for instance. But the main exception was William and Alice, in the house they had built on Irving Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in the rambling New Hampshire farmhouse in Chocorua, New Hampshire, where Henry went upon his arrival in 1904. Cohabitation with William seemed to be without major friction, no doubt because Alice reigned in both places, and also because Henry was a devoted uncle to Harry and Peggy and their siblings.

In the long story of friction, as well as of real affection, between the brothers, William’s seeming judgment that the American continent was too small to hold them both deserves remark. While Henry was in Chicago, William made the sudden decision to depart, alone, for a trip to Greece and Italy, from March through June 1905. He was still abroad when Henry returned to the East Coast from his trip to the Midwest and California. This time, Henry at first stayed in the Brunswick Hotel in Boston, closer to the dentist he was there to see, instead of at Irving Street in Cambridge. William, meanwhile, wrote charming and loving letters home to Alice, wishing she were with him—but he seems never to have considered taking her.

William returned from the European trip on June 11, but then was off again to Chicago on June 28, followed by a trip to lecture to the Summer School of the Cultural Sciences in Keene Valley, in the Adirondacks. So we find Henry staying at 95 Irving Street without William. One would almost conclude that William had had enough of Henry and did not want to cohabit further with him.

***

A similar thought comes to mind when we read the strange story of William, Henry, and the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This was a new organization, sprung from the side of National Institute of Arts and Letters, intended to be something like the Académie française. The original seven academicians selected in 1904 proceeded to elect the subsequent members. Henry James was elected on the second ballot, William on the fourth, in May 1905. But William declined the honor, in a letter in which he characterized the academy, not inaccurately, as “an organization for the mere purpose of distinguishing certain individuals (with their own connivance) and enabling them to say to the world at large ‘we are in and you are out.’ ” William went on to say: “And I am the more encouraged to this course by the fact that my younger and shallower and vainer brother is already in the Academy, and that if I were there too, the other families represented might think the James influence too rank and strong.”

Whatever attempts had been made to pass this off as friendly family joshing, it has a sharp edge of hostility. And as William’s biographer points out, it was not a casual note. William rewrote the letter, making it nastier still: he added “shallower” to “younger” and “vainer” in the final version, as if to put Henry more dramatically in his place. Whatever the closeness of the brothers—and they were indeed close, both citizens of a family in which family ties were of overwhelming importance—the sibling rivalry that must have traced back to childhood was still operative, and still driving William’s psychosocial reactions.

William’s maximal hostility toward Henry transpired in the letter he wrote to him following his reading of The Golden Bowl, which was published in the United States by Charles Scribner’s Sons in November 1904, then in England by Methuen in February 1905. William read the novel during the summer of 1905, and wrote to Henry about it in October. “I read your Golden Bowl a month or more ago, and it put me, as most of your recenter long stories have put me, in a very puzzled state of mind.” He continued “I don’t enjoy the kind of ‘problem,’ especially when, as in this case, it is treated as problematic (viz. the adulterous relations betw. Ch. & the P. [Charlotte Stant and Prince Amerigo]), and the method of narration by interminable elaboration of suggestive reference (I don’t know what to call it, but you know what I mean) goes agin [sic] the grain of all my impulses in writing.” I am not sure what he means by “‘problem’ … treated as problematic”—no doubt the adultery, which a number of American book reviewers couldn’t stomach—though his comment on the method of narration is clear enough, if largely imprecise.

It shows little attempt to understand his brother’s fictional dramas of consciousness, which seems odd, considering his own interest, as a psychologist and philosopher, in states of consciousness. After all, William invented the term stream of consciousness, which doesn’t quite apply to Henry’s work but would to that of many a later modernist. He goes on to say that there is “a brilliancy and cleanness of effect, and in this book especially a high-toned social atmosphere that are unique and extraordinary.” Then comes the stronger censure:

Your methods & my ideals seem the reverse, the one of the other—and yet I have to admit your extreme success in this book. But why won’t you, just to please Brother, sit down and write a new book, with no twilight or mustiness in the plot, with great vigor and decisiveness in the action, no fencing in the dialogue, no psychological commentaries, and absolute straightness in the style? Publish it my name, I will acknowledge it, and give you half the proceeds. Seriously, I wish you would, for you can; and I should think it would tempt you to embark on a “fourth manner.” You of course know these feelings of mine without my writing them down but I’m “nothing if not” outspoken.

There have been plenty of other readers and critics of Henry James over the decades who have deplored the complexities and indirections of his “late manner,” but William does something more than that. He appears to wish to reduce his younger brother to himself, to deny the possibility of another style. The novel he sketches out—one with “vigor and decisiveness” in the action, no “fencing” in the dialogue, and devoid of psychological commentary may be intended as a joke, but it’s a poor one and a hostile one. As for publishing it in William’s name and then receiving but half the royalties—that seems an absolute denial of his brother’s right to an independent existence. All the Jameses could be sharp-tongued with one another, but here William goes beyond intrafamily play. It’s a harsh response to his brother’s masterpiece, a seeming a refusal to try to understand it.

That is what Henry detects in his reply. He begins by appearing to adopt William’s pseudojocular tone: “I mean … to try to produce some uncanny form of thing, in fiction, that will gratify you, as Brother—but let me say, dear William, that I shall be greatly humiliated if you do like it, & thereby lump it, in your affection, with things of the current age, that I have heard you express admiration for & that I would sooner descend to a dishonored grave than have written.” Then he comes to the more serious protest against William’s reading of The Golden Bowl:

But it’s, seriously, too late at night, & I am too tired, for me to express myself on this question—beyond saying that I’m always sorry when I hear of your reading anything of mine, & always hope you won’t—you seem to me so constitutionally unable to “enjoy” it, & so condemned to look at it from a point of view remotely alien to mine in writing it, & to the conditions out of which, as mine, it has inevitably sprung—so that all the intuitions that have been its main reason for being (with me) appear never to have reached you at all—& you appear even to assume that the life, the elements, forming its subject-matter deviate from felicity in not having an impossible analogy with the life of Cambridge.

Henry’s rejection of William’s strictures on his novel becomes a not entirely covert critique of William’s provincialism, his incapacity to see beyond the values of Cambridge, Harvard, and New Hampshire. Which is perhaps fair enough: for all the range and perceptiveness of his writings, and his wide reading of German and French psychologists and philosophers, William’s style, as a writer and a person, seems very much rooted in Cambridge soil, which from early on seemed to Henry unsuited to his longings.

Henry winds up by saying: “It shows how far apart & to what different ends we have had to work out (very naturally & properly!) our respective intellectual lives! And yet I can read you with rapture … Philosophically, in short, I am ‘with’ you almost completely.” It can be argued—and has been—that Henry’s books offer a demonstration of pragmatic thinking and pragmatic ethics in action; the moral dramas of his novels tend to turn on how one treats other people. That William was unable to appreciate how close his brother’s worldview may have been to his own cannot be attributed to stupidity—there’s none of that in either of them. It seems rather to be generated by a kind of psychological blindness that no doubt derives from family dynamics as well as from William’s rejection of his brother’s lack of “manliness.”

One has the impression that Henry spent much of his life dealing with rebuffs from his elder brother, that he was thoroughly used to them and yet continued to be wounded by them. He put an ocean between William and himself yet still yearned to overcome that distance. The scenarios established in childhood don’t die. On the contrary, they persist with the force of unconscious desire, never fully satisfied, by nature never satisfiable, and in this lack of satisfaction a driving force toward further achievement—which certainly characterized the life of both William and Henry—that never brings complete happiness. And never complete harmony between the brothers.

This essay is adapted from Henry James Comes Home, which will be published New York Review Books this month.

Peter Brooks is a literary critic and author of several books of nonfiction, including The Melodramatic Imagination; Reading for the Plot; Henry James Goes to Paris, which won the Christian Gauss Award; and Seduced by Story, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. He is professor emeritus at Yale.

Copyright

© The Paris Review