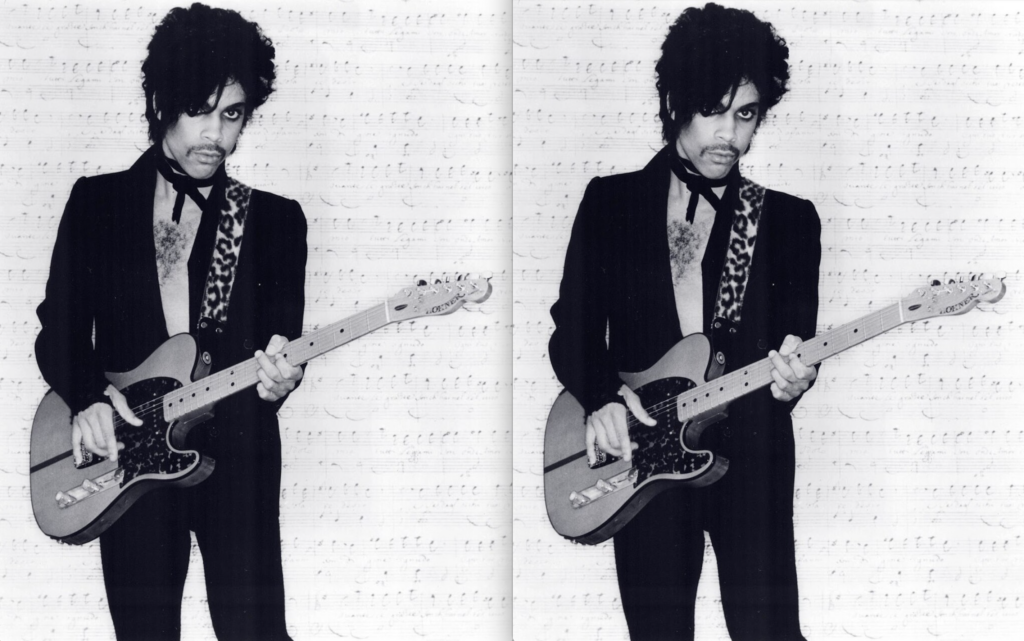

Photograph by Allen Beaulieu, distributed by Warner Bros. Records. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the afterlife and if it’s real. It’s always been hard for me to completely believe in it. I can be skeptical about everything, particularly mystical things. Perhaps because I had learned early on in school that having a spiritual side meant you weren’t as intelligent as other people, and intelligent was what I most wanted to be. The unspoken/spoken law of most academic settings is that to know better is to know that real knowledge has nothing to do with faith. (This is, in part, what my poem in the Review’s Winter issue is about.)

Prince’s song “Let’s Go Crazy” is one of my go-to anthems when I want to think about the purpose of life and what it means to believe beyond plain knowledge. Prince has always been a kind of spiritual guide to me. One of my first poetry chapbooks was named Alphabets & Portraits. For the epigraph, I chose the opening lines of his song “Alphabet St.” as a reminder of what miraculous things poetry can do (“I’m going down to Alphabet Street / I’m gonna crown the first girl that I meet / I’m gonna talk so sexy / She’ll want me from my head to my feet”). These days, the opening monologue of “Let’s Go Crazy” gets to me especially:

Dearly beloved, we have gathered here today

To get through this thing called life

Electric word life, it means forever and that’s a mighty long time

But I’m here to tell you, there’s something else

The afterworld, a world of never-ending happiness

You can always see the sun, day or night

So when you call up that shrink in Beverly Hills

You know the one, Dr. Everything’ll Be Alright

Instead of asking him how much of your time is left?

Ask him how much of your mind, baby

‘Cause in this life things are much harder than in the afterworld

This life you’re on your own

And if the elevator tries to bring you down

Go crazy, punch a higher floor

The song’s upbeat rhythm and the salaciousness of his dig at that overpriced therapist always get my blood pumping when I’m down. I love the possessed elevator in the song, ready to bring you down to hell (or to a life full of low vibrations, which could be the same thing). Who doesn’t strive to “punch a higher floor” daily? When I hear Prince’s encouraging words, I too want to rise above all the bullshit of existence.

Copyright

© The Paris Review