Prince and the Afterworld: Dorothea Lasky and Tony Tulathimutte Recommend

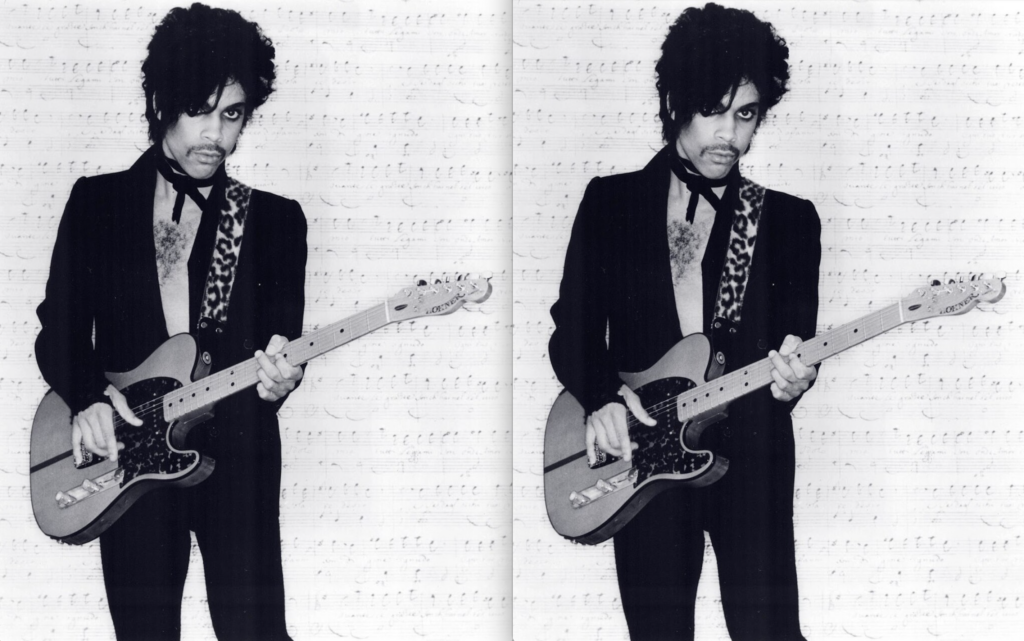

Photograph by Allen Beaulieu, distributed by Warner Bros. Records. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the afterlife and if it’s real. It’s always been hard for me to completely believe in it. I can be skeptical about everything, particularly mystical things. Perhaps because I had learned early on in school that having a spiritual side meant you weren’t as intelligent as other people, and intelligent was what I most wanted to be. The unspoken/spoken law of most academic settings is that to know better is to know that real knowledge has nothing to do with faith. (This is, in part, what my poem in the Review’s Winter issue is about.)

Prince’s song “Let’s Go Crazy” is one of my go-to anthems when I want to think about the purpose of life and what it means to believe beyond plain knowledge. Prince has always been a kind of spiritual guide to me. One of my first poetry chapbooks was named Alphabets & Portraits. For the epigraph, I chose the opening lines of his song “Alphabet St.” as a reminder of what miraculous things poetry can do (“I’m going down to Alphabet Street / I’m gonna crown the first girl that I meet / I’m gonna talk so sexy / She’ll want me from my head to my feet”). These days, the opening monologue of “Let’s Go Crazy” gets to me especially:

Dearly beloved, we have gathered here today

To get through this thing called life

Electric word life, it means forever and that’s a mighty long time

But I’m here to tell you, there’s something else

The afterworld, a world of never-ending happiness

You can always see the sun, day or night

So when you call up that shrink in Beverly Hills

You know the one, Dr. Everything’ll Be Alright

Instead of asking him how much of your time is left?

Ask him how much of your mind, baby

‘Cause in this life things are much harder than in the afterworld

This life you’re on your own

And if the elevator tries to bring you down

Go crazy, punch a higher floor

The song’s upbeat rhythm and the salaciousness of his dig at that overpriced therapist always get my blood pumping when I’m down. I love the possessed elevator in the song, ready to bring you down to hell (or to a life full of low vibrations, which could be the same thing). Who doesn’t strive to “punch a higher floor” daily? When I hear Prince’s encouraging words, I too want to rise above all the bullshit of existence.

But really it’s Prince’s idea of the afterworld that speaks to me in these sad, wintry days. As he sings: I’m here to tell you, there’s something else.” There’s something else, he says, with conviction.

I want to believe him. I want to believe him with a faith so huge it is beyond knowledge. I want to understand how in six words (“Electric word life, it means forever”) Prince tells me everything about being alive and also maybe all about dying. The cool blue David Lynch tone of those two words, electric and life, both bound together by language. Both freed by it, too. An electricity like the endless stream of life and love, just as Jack Spicer writes of in his poem “A Book of Music”:

No love is

Like an ocean with the dizzy procession of the waves’ boundaries

From which two can emerge exhausted, nor long goodbye

Like death.

Spicer was right about love. Prince was right, too. What an electric word life is. What an electric word love is, too. And if there is an afterworld, then it must be full of love and almost nothing else.

To go crazy for love. That’s what Prince challenges us to do these days in his gleaming song.

—Dorothea Lasky, author of “Mother”

Return of the Obra Dinn, a 2018 indie video game by Lucas Pope, sounds a bit boring when you summarize it, which is to say, it’s literature. You play an insurance investigator for the East India Company in 1807, on board a ship that has mysteriously reappeared after vanishing five years earlier. Your task is to find out how each passenger died or escaped. Helpfully, your magic pocket watch lets you visit the instant of people’s deaths at will, so you get to walk around inside these frozen moments like they’re life-size dioramas, using observation and deduction to fill out your ledger of casualties, a process best described as forensic Moby-Dick sudoku. Obra Dinn’s retro one-bit graphics are done in a careful pointillist black-and-white (though the “black” is more of a Pullman green), and the abstraction this introduces is more tantalizing than obfuscating, making it feel more like you’re investigating a hazy memory than a crime scene. The game will have you distinguishing between nineteenth-century English accents, googling what a bosun does, identifying various hats, and reflecting on just how many stupid ways one can die at sea. Obra Dinn should do plenty to quell your appetite for a historical Lovecraftian maritime murder mystery—though if you end up hungry for more death, a brilliant homage can be enjoyed in Color Gray Games’s 2022 game The Case of the Golden Idol.

—Tony Tulathimutte, author of “Ahegao”

Copyright

© The Paris Review