Photograph by Sean Zanni/PMC.

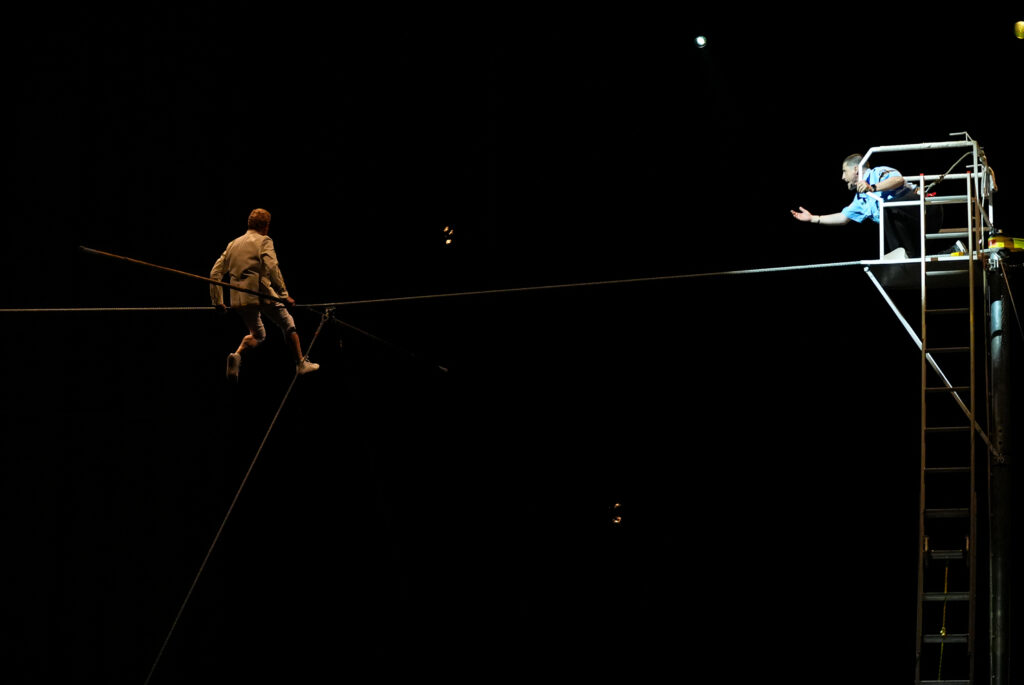

There was an air of subdued anticipation at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine as we waited for Philippe Petit to take the stage. A clarinetist roved through the church improvising variations on Gershwin in spurts, making it hard to tell if the event, which was being held to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Petit’s walk between the Twin Towers, had begun. Eventually, the lights dimmed and we were told to turn off our phones, as even a single lit screen in the audience might cause Petit to fall from his tightrope. Music started, but so quietly that it seemed like it was being played from a phone, while a candlelit procession made its way down the nave. Large boards were set up, on which footage of the Twin Towers being constructed was projected. A group of child dancers imitated Petit’s walk along the ground, and were followed by a professional whistler. After we were shuffled through this sequence that felt like a performed version of ADHD, Petit finally appeared and began walking, first meekly, then quickly, to Satie’s “Gymnopédie No. 1,” wearing a white jacket laced with gold.

The original Twin Towers walk took place on the morning of August 7, 1974, after Petit and a group of conspirators broke into the World Trade Center while it was still partially under construction, and used a bow and arrow to span a tightrope between the towers. Petit walked, ran, lay down, and knelt on the wire, a quarter of a mile in the air, as the city looked on from below. It had taken more than eight months of meticulous planning to carry out the performance, including creating a mock-up of the distance between the Towers on a field in France, studying their engineering, and using various disguises and fake IDs to gain access to them. These heist-like aspects (it is referred to as “the coup”) have made it ripe material for movies including Man on Wire and The Walk, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit and featuring CGI Twin Towers.

***

Three weeks before the performance, Petit held a reception in anticipation of the event on the eightieth floor of 3 World Trade Center. I exited the elevator into a space with perhaps the most impressive view of New York I’d ever seen. Under the influence of the height and temperature change (it was a hundred degrees outside that day), the vista was so impressive that it was almost addictive; it was hard to pull myself away from the windows, as though the space were designed to keep me there, like the interior of a casino.

Copyright

© The Paris Review