Self-Portrait in the Studio

All images courtesy of the author.

A form of life that keeps itself in relation to a poetic practice, however that might be, is always in the studio, always in its studio.

Its—but in what way do that place and practice belong to it? Isn’t the opposite true—that this form of life is at the mercy of its studio?

***

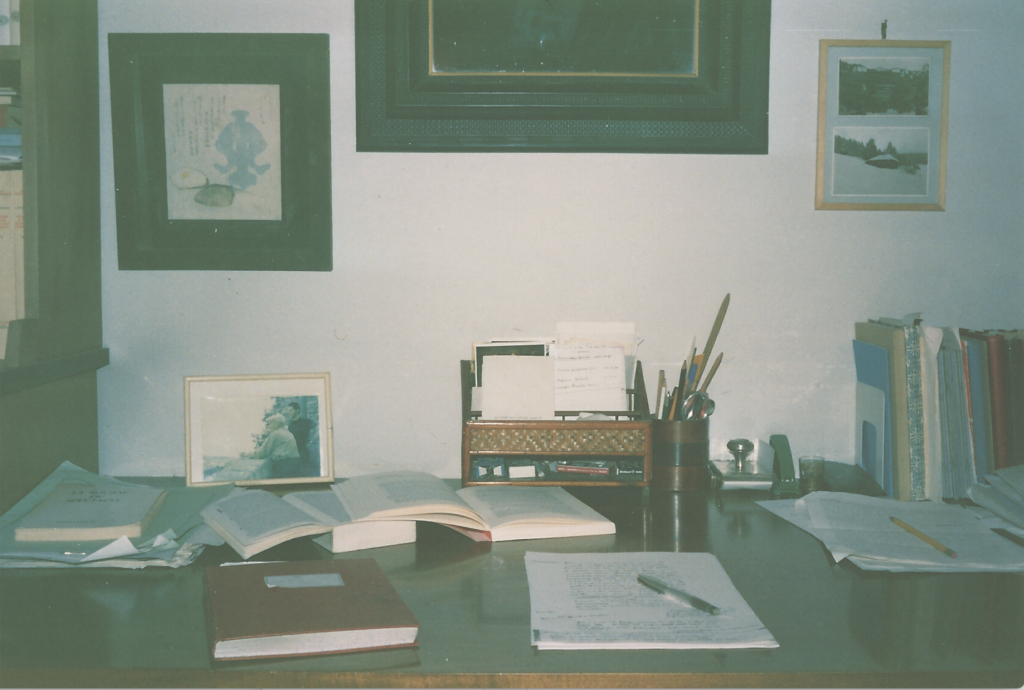

In the mess of papers and books, open or piled upon one another, in the disordered scene of brushes and paints, canvases leaning against the wall, the studio preserves the rough drafts of creation; it records the traces of the arduous process leading from potentiality to act, from the hand that writes to the written page, from the palette to the painting. The studio is the image of potentiality—of the writer’s potentiality to write, of the painter’s or sculptor’s potentiality to paint or sculpt. Attempting to describe one’s own studio thus means attempting to describe the modes and forms of one’s own potentiality—a task that is, at least on first glance, impossible.

***

How does one have a potentiality? One cannot have a potentiality; one can only inhabit it.

***

Habito is a frequentative of habeo: to inhabit is a special mode of having, a having so intense that it is no longer possession at all. By dint of having something, we inhabit it, we belong to it.

***

The objects of my studio have remained the same, and years later in the photographs of them in different places and cities, they seem unchanged. The studio is the form of its inhabiting—how could it change?

***

In the wicker letter tray against the wall at the center of the desk in both my studio in Rome and the one in Venice, on the left there is an invitation to the dinner celebrating Jean Beaufret’s seventieth birthday, on the front of which is written this line from Simone Weil: “Un homme qui a quelque chose de nouveau à dire ne peut être d’abord écouté que de ceux qui l’aiment.” The invitation carries the date May 22, 1977. Since then, it has always remained on my desk.

***

One knows something only if one loves it—or as Elsa would say, “only one who loves knows.” The Indo-European root that means “to know” is a homonym for the one that means “to be born.” To know [conoscere] means to be born together, to be generated or regenerated by the thing known. This, and nothing but this, is the meaning of loving. And yet, it is precisely this type of love that is so difficult to find among those who believe they know. In fact, the opposite often occurs—that those who dedicate themselves to the study of a writer or an object end up developing a feeling of superiority towards them, almost a sort of contempt. This is why it is best to expunge from the verb “to know” all merely cognitive claims (cognitio in Latin is originally a legal term meaning the procedures for a judge’s inquiry). For my own part, I do not think we can pick up a book we love without feeling our heart racing, or truly know a creature or thing without being reborn in them and with them.

***

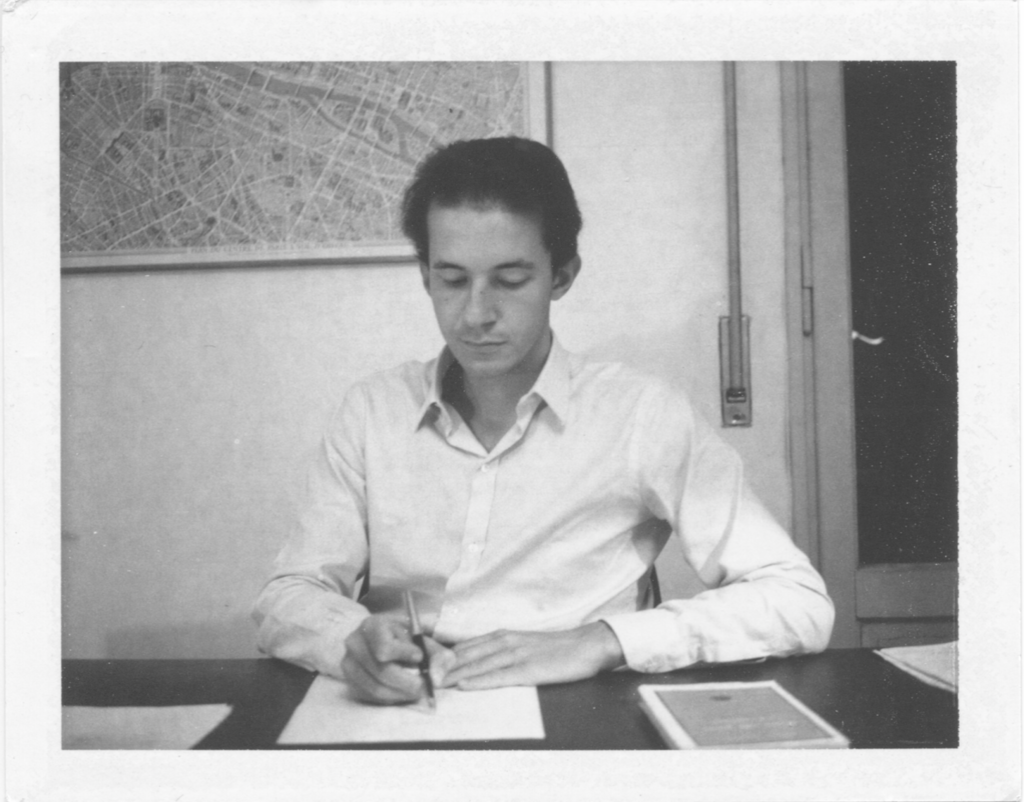

The photograph with Heidegger to my left, in my studio on Vicolo del Giglio in Rome, was taken in the countryside of Vaucluse during one of the walks that punctuated the first seminar at Le Thor in 1966. At a distance of half a century, I cannot forget the landscape of Provence immersed in the September light, the white rocks of the boris, the great, steep hump of Mont Ventoux, the ruins of Sade’s Château de Lacoste perched on the rocks. And the feverish, star-pierced night sky, which the moist gauze of the Milky Way seemed to want to soothe. It is perhaps the first place I wanted to hide my heart—and there, untouched and unripe as it was, my heart must have remained, even if I could no longer say where—perhaps under a boulder in Saumane, in a cabin of Le Rebanqué, or in the garden of the little hotel where Heidegger held his seminar every morning.

***

What did the meeting with Heidegger in Provence mean to me? I certainly cannot separate it from the place where happened—his face at once gentle and stern, intense and uncompromising eyes that I have never seen elsewhere save in a dream. In life there are events and meetings that are so decisive that it is impossible for them to enter into reality completely. They happen, to be sure, and the mark out the path—but they never cease to happen, so to speak. Continuous meetings, in this sense, as theologians say that God never ceases to create the world, that there is a continuous creation of the world. These meetings never cease to accompany us until the end. They are part of what remains unfinished in a life, what goes beyond it. And what goes beyond life is what remains of it.

***

I remember, in the dilapidated church of Thouzon, which we visited on one of our excursions in Vaucluse, the Cathar dove carved inside the architrave of a window in such a way that no one could see it without looking in the opposite of the usual direction.

***

That small group of men who, in the photograph from September 1966, walk together toward Thouzon—what ever became of it? Each in his own way had more or less consciously meant to make something of his life—the two seen from the back on the right are René Char and Heidegger, behind them myself and Dominique—what became of them, what became of us? Two have been dead a long time; the other two are, as they say, getting on in years (getting on toward what?). What matters here is not work, but life. Because on that late sunny afternoon (the shadows are long) they were alive and felt it, each intent in his thoughts, that is, in the bit of good that he had glimpsed. What has become of that good, wherein thought and life were not yet divided, wherein the feeling of the sun on the skin and the shadow of words in the mind so happily merged?

***

Smara in Sanskrit means both love and memory. We love someone because we remember them and, vice versa, we remember because we love. In loving we remember and in remembering we love, and in the end we love the memory—that is, love itself—and we remember love—that is, memory itself. This is why loving means being unable to forget, being unable to get a face, a gesture, a light out of your mind. But in truth it also means that we can no longer have a memory of it, that love is beyond memory, immemorably, ceaselessly present.

***

A page from Nicola Chiaromonte’s notebooks contains an extraordinary meditation on what remains of a life. For him the essential issue is not what we have or have not had—the true question is, rather, “what remains? . . . what remains of all the days and years that we lived as we could, that is, lived according to a necessity whose law we cannot even now decipher, but at the same time lived as it happened, which is to say, by chance?” The answer is that what remains, if it remains, is “that which one is, that which one was: the memory of having been ‘beautiful,’ as Plotinus would say, and the ability to keep it alive even now. Love remains, if one felt it, the enthusiasm for noble actions, for the traces of nobility and valor found in the dross of life. What remains, if it remains, is the ability to hold that what was good was good, what was bad was bad, and that nothing one might do can change that. What remains is what was, what deserves to continue and last, what stays.”

The answer seems so clear and forthright that the words that conclude the brief meditation pass unobserved: “And of us, of that Ego from which we can never detach ourselves and which we can never abjure, nothing remains.” And yet, I believe that these final, quiet words lend sense to the answer that precedes them. The good—even if Chiaromonte insists on its “staying” and “lasting”—is not a substance with no relation to our witnessing of it—rather, only this “of us nothing remains” guarantees that something good remains. The good is somehow indiscernible from our cancelling ourselves in it; it lives only by the seal and arabesque that our disappearance marks upon it. This is why we cannot detach ourselves from ourselves or abjure ourselves. Who is “I”? Who are “we”? Only this vanishing, this holding our breath for something higher that, nevertheless, draws life and inspiration from our bated breath. And nothing says more, nothing is more unmistakably unique than that tacit vanishing, nothing more moving than that adventurous disappearance.

***

Every life always runs along two levels: one seemingly governed by necessity, even if, as Chiaromonte writes, we cannot decipher its law, and another that is abandoned to chance and contingency. There is no point in pretending there is some arcane, demonic harmony between these two (this is the hypocritical claim that I was never able to accept in Goethe), and yet, once we manage to look at ourselves without disgust, the two levels, though uncommunicating, do not exclude or contrast with each other; rather, they offer each other a sort of serene, reciprocal hospitality. This is the only reason why the thin fabric of our life can slip out of our hands almost imperceptibly, while the facts and events—that is, the errors—that lay its warp attract all our attention and all our useless care.

***

What accompanies us through life is also what nourishes us. To nourish does not simply mean to make something grow; above all, it means to let something reach the state to which it naturally tends. The meetings, the readings, and the places that nourish us help us to reach this state. And yet, something in us resists this maturation and, just when it seems close, stubbornly stops and turns back toward the unripe.

A medieval legend about Virgil, whom popular tradition had turned into a magician, relates that upon realizing he was old he employed his arts to regain his youth. After having given the necessary instructions to a faithful servant, he had himself cut up into pieces, salted, and cooked in a pot, warning that no one should look inside the pot before it was time. But the servant—or, according to another version, the emperor—opened the pot too soon. “At the point,” the legend recounts, “there was seen an entirely naked child who circled three times around the tub containing the meat of Virgil and then vanished and of the poet nothing remained.” Recalling this legend in the Diaspalmata, Kierkegaard bitterly comments, “I dare say that I also peered too soon into the cauldron, into the cauldron of life and the historical process, and most likely will never manage to become more than a child.”

Maturing is letting oneself be cooked by life, letting oneself blindly fall—like a fruit—wherever. Remaining an infant is wanting to open the pot, wanting to see immediately even what you are not supposed to look at. But how can one not feel sympathy for those people in the fables who recklessly open the forbidden door.

In her diaries, Etty Hillesum writes that a soul can be twelve years old forever. This means that our recorded age changes with time but the soul has an age of its own that remains unchanged from birth to death. I don’t know the exactly age of my soul, but it surely cannot be very old, in any case not more than nine, judging from the way I seem to recognize it in my memories from that age, which have thus remained so vivid and sharp. Every year that passes, the gap between my recorded age and the age of my soul widens and the feeling of this difference is an ineliminable part of the way I life my life, of both its great imbalances and its precarious equilibriums.

***

You can make out the title of the book lying on the left side of the desk on Vicolo del Giglio: La société du spectacle by Guy Debord. I don’t remember why I was rereading it—I first read it back in 1967, the very year of its publication. Guy and I became friends many years later, at the end of the eighties. I remember my first meeting with Guy and Alice at the bar of the Lutetia, the immediately intense conversation, the sure agreement about every aspect of the political situation. We had both arrived at one and the same clarity, Guy starting from the tradition of the artistic avant-gardes, myself from poetry and philosophy. For the first time I found myself speaking about politics without having to bang against the obstacle of useless and misguided ideas and writers (in a letter Guy wrote to me some time later, one of these glibly exalted writers was soberly liquidated as ce sombre dément d’Althusser . . . ) and the systematic exclusion of those who could have oriented the so-called movements in a less ruinous direction. In any case, it was clear to both of us that the main obstacle barring the way to a new politics was precisely what remained of the Marxist tradition (not of Marx!) and the workers’ movement, which was unwittingly complicit with the enemy it believed it was combatting.

During our subsequent meetings at his house on the rue du Bac, the relentless subtlety—worthy of a magister of Vico de li Strami or a seventeenth-century theologian—with which he analyzed both capital and its two shadows, one Stalinist (the “concentrated spectacle”) and one democratic (the “diffuse spectacle”), never ceased to amaze me.

***

The true problem, however, lay elsewhere—closer and, at the same time, more impenetrable. Already in one of his first films Guy had evoked “that clandestinity of private life regarding which we possess nothing but pitiful documents.” It was this most intimate stowaway that Guy, like the entire western political tradition, could not get to the bottom of. And yet the term “constructed situation,” from which the group took its name, implied that it was possible to find something like “the northwest passage of the geography of real life.” And if in his books and films Guy comes back so insistently to his biography, to the faces of his friends and the places where he had lived, it is because he obscurely sensed that this was exactly where the secret of politics lay hidden, the secret on which every biography and every revolution could not but run aground. The genuinely political element consists in the clandestinity of private life, and yet, if we try to grasp it, it leaves us holding only the incommunicable, tedious quotidian. It was the political significance of this stowaway—which Aristotle had, with the name zōē, both included in and excluded from the city—that I had begun to investigate in those very same years. I, too, albeit in a different way, was seeking the northwest passage of the geography of real life.

Guy did not care at all about his contemporaries, and he no longer expected anything from them. As he once told me, for him the problem of the political subject by now boiled down to the alternative between homme ou cave (to explain the meaning of this unknown argot term, he pointed me to a Simonin novel that he seemed fond of, Le cave se rebiffe). I do not know what he might have thought of the “whatever singularity” that years later the Tiqqun group would make—with the name Bloom—the possible subject of the politics to come. In any case, when some years later he met the two Juliens—Coupat and Boudart—and Fulvia and Joël, I could not have imagined a closeness and, at the same time, distance greater than the one that separated them from him.

In contrast to Guy, who read narrowly but insistently (in the letter he wrote to me after reading my “Marginal Notes on Commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle” he referred to the writers I had cited as “quelques exotiques que j’ignore très regrettablement et [ . . . ] quatre ou cinque Français que je ne veux pas du tout lire”), in the readings of Julien Coupat and his young comrades you would find the author of the Zohar mingling with Pierre Clastres, Marx with Jacob Frank, De Martino with René Guénon, Walter Benjamin with Heidegger. And while Debord no longer hoped for anything from his peers—and if one despairs of others one also despairs of oneself—Tiqqun had wagered—albeit with all possible wariness—on the common man of the twentieth century, the Bloom as they called him, who precisely insofar as he had lost all identity and all belonging could be capable of anything, for better and for worse.

Our long discussions in the locale at 18 rue Saint-Ambroise—a café that they had left as it was, with its sign Au Vouvray, which still drew in a few passersby by mistake—and at the Verre à pied in Rue Mouffetard have remained as vivid in my memory as those that had animated the evenings at the farmhouse in Montechiarone in Tuscany ten years earlier.

***

In this farmhouse that Ginevra and I—following an unfathomable whim of that spirit that wanders where it will—rented in the Sienese countryside between 1978 and 1981, we spent evenings with Peppe, Massimo, Antonella, and later, Ruggero and Maries, that I can only describe as “unforgettable”—even if, as is the case with every truly unforgettable thing, there now remains nothing but a cloud of insignificant details, as if their truer meaning had sunk into the abyss somewhere—but the abyss, in heraldry, is the center of the shield and the unforgettable resembles an empty blazon. We talked about everything, a passage from Plato or Heidegger, a poem by Caproni or Penna, the colors in one of Ruggero’s painting or anecdotes from friends’ lives, but as in an ancient symposium, everything found its name, its delight, and its place. All this will be lost, is already lost, entrusted to the uncertain memory of four or five people and soon to be forgotten entirely (a faint echo of it can be found in the pages of the seminar on Language and Death)—but the unforgettable remains, because what is lost is God’s.

***

(What am I doing in this book? Am I not running the risk, as Ginevra says, of turning my studio into a little museum through which I lead readers by the hand? Do I not remain too present, while I would have liked to disappear in the faces of friends and our meetings? To be sure, for me inhabiting meant to experience these friendships and meetings with the greatest possible intensity. But instead of inhabiting, is it not having that has got the upper hand? I believe I must run this risk. There is one thing, though, that I would like to make clear: that I am an epigone in the literal sense of the word, a being that is generated only out of others, and that never renounces this dependency, living in a continuous, happy epigenesis).

***

From the window on Vicolo del Giglio you could see only a roof and a facing wall whose plaster, deteriorated in many places, left glimpses of bricks and stones. For years my gaze must have fallen, even distractedly, on that piece of ocher wall burnished by time, which only I could see. What is a wall? Something that guards and protects—the house or the city. Childlike tenderness of Italian cities, still enclosed within their own walls like a dream that stubbornly seeks shelter from reality. But a wall does not merely keep things out; it is also an obstacle that you cannot overcome, the Unsurmountable with which sooner or later you must contend. As every time one comes up against a boundary, various strategies are possible. A boundary is what separates an inside from an outside. We can, then, like Simone Weil, think of a wall as such, so that it remains thus up to the end, with no hope of leaving the prison. Or rather, like Kant, we might make the boundary the essential experience, which grants us a perfectly empty outside, a sort of metaphysical storage space in which to place the inaccessible Thing in itself. Or instead, like the land surveyor K., we might question and circumvent the borders that separate the inside from the outside, the castle from the village, the sky from the earth. Or even, like the painter Apelles in the anecdote related by Pliny, cut the borderline with an even finer line in such a way that outside and inside switch sides. Make the outside inside, as Manganelli would say. In any case, the last thing to do is bang our heads against it. The last—in every sense.

Translated from the Italian by Kevin Attell.

From Self-Portrait in the Studio, to be published this October by Seagull Books.

Giorgio Agamben is one of Italy’s foremost contemporary thinkers.

Copyright

© The Paris Review