If I wasn’t reading as a kid, I was playing with dolls. I still find dolls fascinating and beautiful. I love the variety of dolls, from baby dolls to fashion dolls to artist’s mannequins. I love the rich history of dolls and how entwined doll history is with culture. One of the world’s first and most popular dolls, the paper doll, continues to thrive in new ways with doll enthusiasts of all ages. Since paper is such a delicate art form, not many whole pieces have survived history. However, paper art and paper dolls can be traced back thousands of years.

Historical Paper Arts

The predecessors of the modern paper doll were different variations of paper art across the world.

In Japan, early origami took the shape of figures in kimono. Paper art and doll making are historically linked in Japan. Hinamatsuri, or Doll’s Day, is celebrated on March 3 with expensive heirloom dolls crafted from wood, paper, and clay. The wayang puppets of Java and Bali have been in use since ancient times. Made of leather, wood, or paper, these delicately carved puppets are used to tell the stories of Hindu folklore, local stories and legends, and historical events.

The first paper dolls of Europe appeared in Slavic countries, where paper crafts continue to thrive. Paper cutting folk art, or wycinaki in Polish, began to appear around the 15th century. As popularity rose, more figures began to appear in the art. Wycinaki is and was part of home decor, toys, furniture, and gifts.

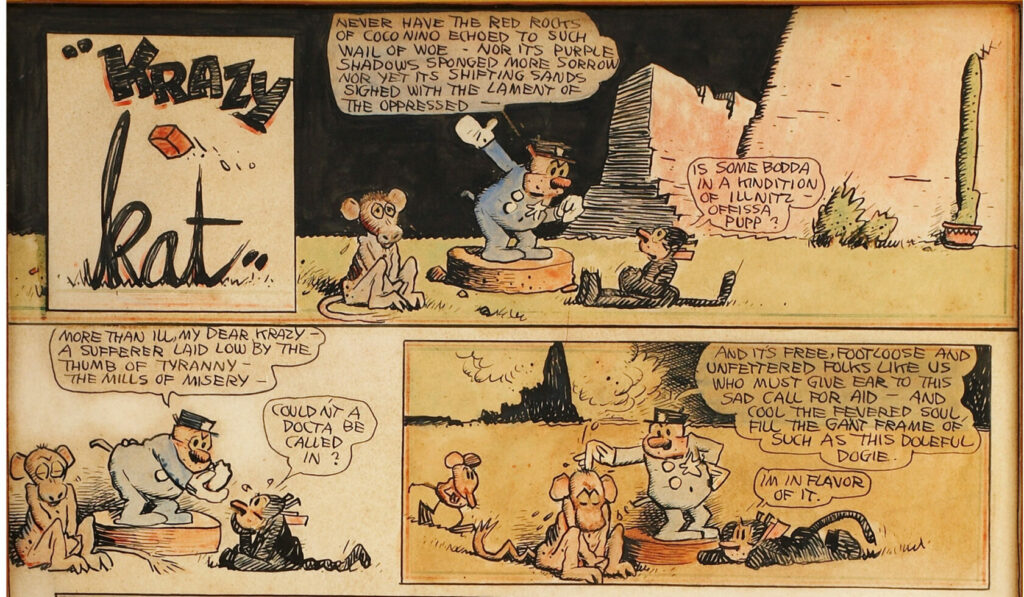

French jointed puppets, called pantins, were first fashioned after famous 17th century figures. This satirical figures were among the first mechanical toys in the west. Other common pantin figures were Commedia dell ‘arte characters, like Harlequin, Pulcinella, and Pierrot, the clowns. The early hand painted pantins were simplistic, but as printing technology progressed, more detail could be added to mass production pantins. Printed pantins and paper dolls had the advantage of intricate detail over their manufactured porcelain cousins. Mass produced pantins were printed on a sheet, much like current paper dolls, with limbs separate from the bodies. Each piece was to be cut out separately, then strings, brads, or other fastenings attached to limbs to make the dolls jump and dance. Early paper toys share a similar look to contemporary paper dolls, but even pantins, dressed up like their contemporary counterparts did not come with an assortment of paper fashions and accessories.

Copyright

© Book Riot