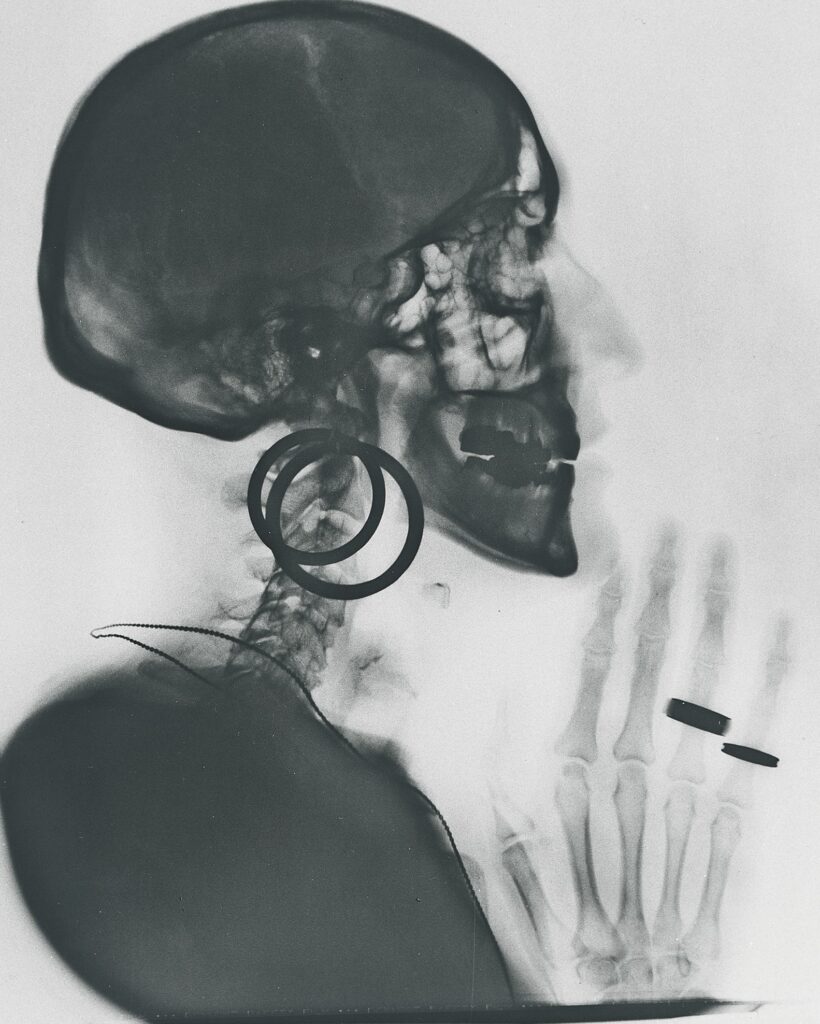

Virginia Albert, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

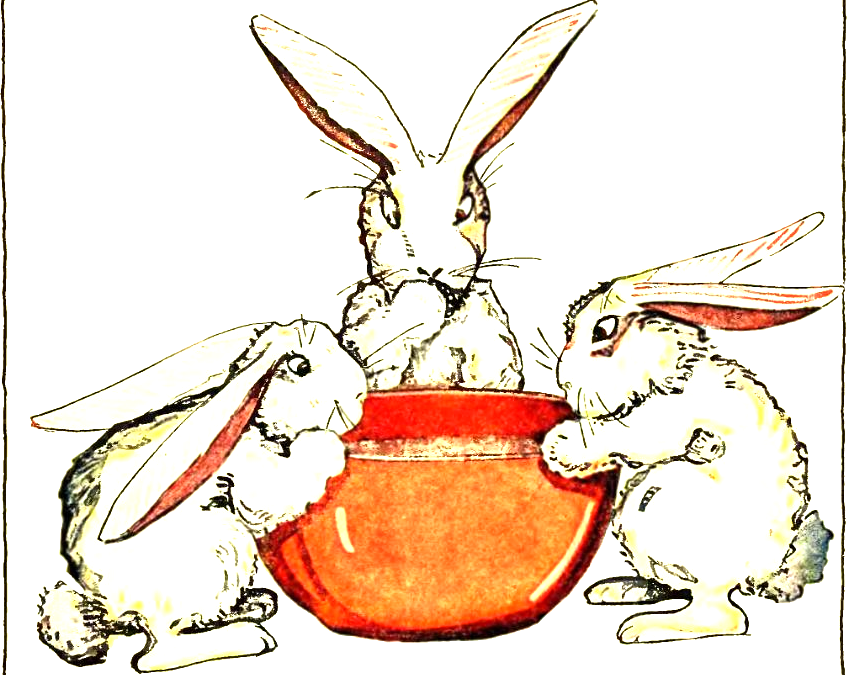

Sometime between midnight and 2 A.M. last night, I ordered a second copy of Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present. The book, a collaboration between Charlotte Zolotow and Maurice Sendak, was published sixty years ago. Sendak won a Caldecott for his eerie, dioramic illustrations, which look like they were executed in oil pastel, or perhaps in thick-tipped colored pencil. They’re sketchier and more impressionistic than the exacting Sendak lines I’m familiar with from Where the Wild Things Are and Outside Over There, but just as unnerving. Mr. Rabbit is a proto–Slender Man, lounging louchely around a little girl in a pink twinset who’s just out to find a birthday present for her mother.

“Mr. Rabbit,” said the little girl, “I want help.”

“Help, little girl, I’ll give you help if I can,” said Mr. Rabbit.

“Mr. Rabbit,” said the little girl, “it’s about my mother.”

“Your mother?” said Mr. Rabbit.

“It’s her birthday,” said the little girl.

“Happy birthday to her then,” said Mr. Rabbit.

The book consists only of dialogue, all of which Zolotow imbues with this distinctly creepy cadence and rhythm. Mr. Rabbit helps the little girl figure out what her mother likes (“red”). When she realizes she can’t give her mother “red,” he offers some alternatives: a fire engine, a red roof, underwear. (I think the book would still be unnerving without this humanoid rabbit suggesting red underwear as a suitable gift from child to parent, but it’s one of the more deliciously sinister moments.) The little girl decides on apples, but determines that she needs more for her mother. Her mother likes other colors, too—yellow and green and blue—so Mr. Rabbit helps her to find suitable accompaniments to apples in all of those hues. For blue, he first suggests sapphires, even though the girl has already said she can’t afford emeralds—such a caddish, cruel companion for a child! Proposing absurd, impossible gifts: gems and the stars and taxicabs! In the end, an entire fruit basket comes together, and the little girl thanks Mr. Rabbit and bids him farewell; he returns the goodbye, adding, “and a happy birthday and a happy basket of fruit to your mother.”

My three-year-old son loves this book. He loves it so much he doesn’t mind that our current copy, a staple-bound paperback retired from the Minnesota library system, is missing several key pages (all of “yellow” and parts of “green”) so that it jumps abruptly from Bartlett pears to blue grapes. But I thrill to imagine his joy when I present him with this new copy, and my own, when I take the old paperback, slice out the pages, and hang them on the wall. I wonder: How many more times will my son sit in my lap or stand against the pillows on the bed, leaning over my shoulder, as we’re held in thrall by this incantatory rabbit, reading this lovely present?

Copyright

© The Paris Review