Over the course of Villa Albertine’s Proust Weekend, a series of talks, workshops, and readings celebrating the forthcoming English translation of the last volume of the Recherche and the centenary of Proust’s death, I ate more cakes per diem than usual: on Sunday afternoon, a miniature pistachio financier, a Lego-shaped and moss-textured cake that reminded me of the enormous chartreuse muffins at my college cafeteria; on Saturday morning, a crisp, disc-like, almond-sliver-sprinkled shortbread cookie with a hole, which reminded me of a Chinese coin; and, on Friday night, at a holiday party, a dish of Reddi-wip and sour cream studded with canned mandarin slices and maraschino cherries apparently called ambrosia salad. It reminded me of the music video for Katy Perry’s “California Gurls.” But these were really only preliminary research exercises for the episode in which Proust Weekend was to culminate: a “Proust-inspired madeleine event with surprise guests”!

In the meantime, I attended some panels. When Lydia Davis was beamed in to talk about her award-winning translation of Swann’s Way, I stared at the cat in the lower left-hand corner of the screen. In order to be properly Proustian, I knew, the center of an experience would be hidden in the margins of the event itself. The events of the Weekend transpired in the second-floor ballroom of the Gilded Age mansion that houses Villa Albertine, the French embassy–adjacent artist’s residency program that had organized the event. Most attendees were, I gathered, elderly residents of the Upper East Side and/or miscellaneous French people. The Payne Whitney Mansion seemed like a memory palace designed expressly for the contents of the Recherche: ceilings bordered by Rococo botanical motifs as rhizomatic as Proust’s syntax; or a purple-carpeted grand staircase bookended by two urns of exotic flora that reminded me of Combray’s psychedelically hued asparagus (“steeped in ultramarine and pink, whose tips, delicately painted with little strokes of mauve and azure, shade off imperceptibly down to their feet”).

On Sunday at four, Proust Weekenders would be getting an exclusive “first taste” of a special collaboration between Villa Albertine and the Ladurée pastry franchise: a madeleine-flavored macaron. I’m not sure why macarons were chosen instead of madeleines—perhaps because “macarons,” according to the president of Ladurée US, Elisabeth Holder, “are the supermodels of the food industry.” As I took my seat in the ballroom, I recalled all the Ladurée products I had consumed in the past year: most recently, rose petals suspended in a luminous pink jelly, on my birthday, which is also the date of Proust’s death; a turquoise macaron that I selected from a box of six others because I knew it was called the “Marie Antoinette”; half of the “Champs-Élysées Breakfast” served at Ladurée Soho (disgusting); approximately ten or twelve macarons of various colors, at an event for which I signed an NDA on an iPad at the door; and, last winter, an orange-colored macaron with a tiger printed on it. This last macaron, a Lunar New Year limited edition of some Asian flavor (mango? passion fruit?), gave me pause. Whenever I go into a Ladurée, the store is filled with Asian girls making their Asian boyfriends take pictures of them with their macarons—just like me. The franchise called Paris Baguette is actually Korean. The most recognizably Japanese fashions are strange perversions of those once worn at Versailles. Why do Asian girls love French things/sweets so much? I wondered, not for the first time.

Meanwhile, the madeleine event had begun. And the Villa Albertine had a surprise for us: there would be not one but three madeleine reinterpretations to be tasted tonight! We clapped and cheered. We were hungry. The interpretations sat on a small table at the front of the ballroom, arrayed in order of height. Behind them sat three French pastry chefs.

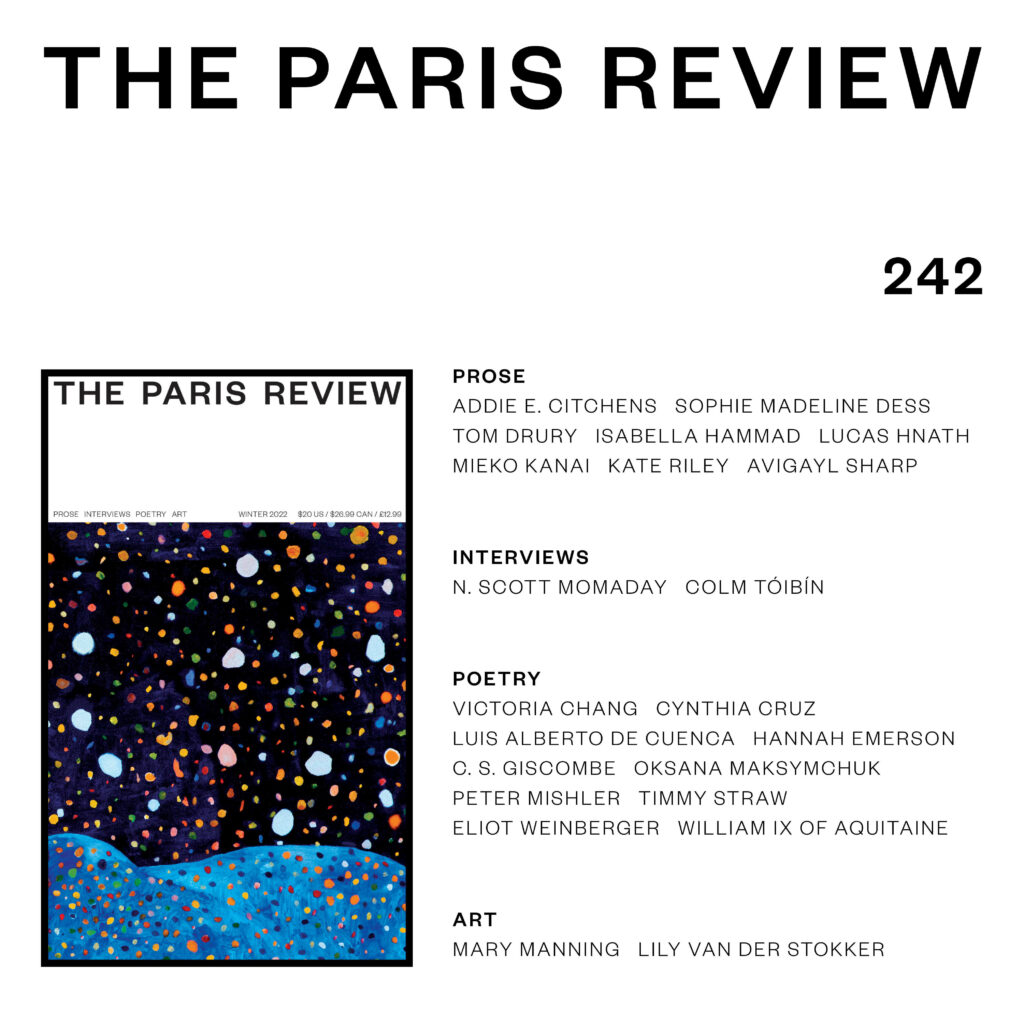

Copyright

© The Paris Review