If Kim Novak Were to Die: A Conversation with Patrizia Cavalli

I first met Patrizia Cavalli in 2018, in her apartment near Campo de’ Fiori, where we drank tea with honey and talked from early afternoon until sunset. Every surface was covered with books, papers, notebooks, scissors, and scarves, and each bore the same handwritten note, a warning to visitors: “Do not move! If you move anything, I’ll kill you.” Over the course of two years, we had three more conversations, speaking for five hours at a stretch. The apartment had been her home for decades: in the late sixties, as a twenty-year-old philosophy student, she rented a single room there; she had just left Todi, the town in Umbria where she grew up, and in Rome she felt unmoored and lonely. In 1969, through a mutual friend, she met the writer Elsa Morante, who was then working on her novel History. Morante was the first person to look at Cavalli’s poems, and after reading them, she called to say, “Patrizia, I’m happy to tell you that you are a poet.”

More than fifty years later, Cavalli’s poems are translated and loved across Europe and the United States. Her first collection, My Poems Won’t Change the World (1974), signaled the forthrightness and disregard for authority that would characterize all her work. Cavalli examines the causes and conditions of pleasure and pain, and the moments in life, often imperceptible at the time, that herald change. Her work explores infatuation, boredom, deception, conflict, grief—all in a poetic voice whose nonchalance belies its artistry.

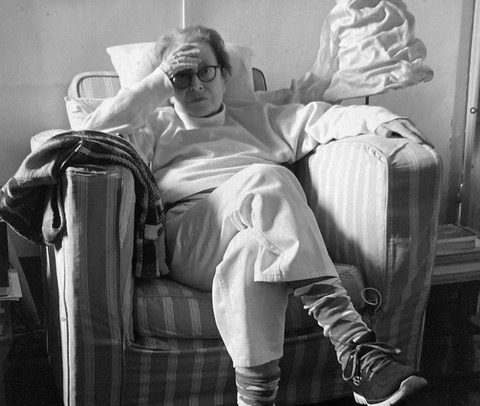

When Cavalli died in June, it felt as though all of Rome wanted to pay tribute. A beautiful ceremony took place at the Campidoglio, where flowers were piled upon flowers. Her admirers and friends crowded the stairwell, and the room where her body lay in state. Cavalli might have criticized the extravagant floral arrangements, but she would have been moved by the words her loved ones chose to speak—some of them her own.

INTERVIEWER

How did you start writing poems?

PATRIZIA CAVALLI

My first poems were written for Kim Novak, in the fifth grade, after I saw the film Picnic. At one point, Novak is coming down the stairs, blond and beautiful, clapping her hands in time to the music that’s playing, and William Holden is watching her, fascinated, and he leaves the other woman to dance with her. I fell in love, went home, fasted for a week in protest because I’d never be able to know Kim Novak—and after the fast I wrote two poems. I found them recently while going through some old notebooks. One is titled “If Kim Novak were to die.” “Where are those black clothes of mine?” I wrote. “Where is the grief that shows on the outside? It’s not there? Well, doesn’t matter. I’ll have precocious grief in this deep heart of mine.”

This is what I’ve always done in my poems—they begin from something physical. I am sustained by eros when I write. Now, with this illness—this cancer that was diagnosed in 2015—it’s as if I’ve lost the memory of certain passionate feelings. But I haven’t lost my ear. I can hear when a word isn’t the exact word. Poetry is about being precise. The word must surprise you even in its necessity, as if you were hearing it for the first time. You should never slide into habits of speech, because there’s nothing more beautiful, more startling, than language. “Thinking about you / might let me forget you, my love.” This couplet, it glides into the air—do you hear it? Poetry knows how to glide into the air.

INTERVIEWER

So you’ve been writing since the fifties. Were you difficult as a child? Your book of essays, Con passi giapponesi (With Japanese steps), is a portrait of your mother and her sadness.

CAVALLI

My mother was in a state of despair, but for her own reasons. She’d chase me around the house with the rug beater; she’d wait behind a door to surprise me with a beating. But I’ve always done whatever I wanted—I’ve never asked anyone for permission. I wanted to get sick, to contract pneumonia or something else serious, so that my mother would feel it was her fault. I tried everything—I’d go into a freezing cave when I was hot, or stand out in the rain to drench myself. But my health withstood every assault, so I could never avenge myself against her that way.

As an adolescent, I’d go and get drunk in the countryside, and we’d have to be taken home all passed out, me and my girlfriends—I was always corrupting them. We’d drink gin because I’d read that Billie Holiday drank gin. I was living a dissolute life, truly dissolute. I’d ask truck drivers for rides, or challenge them to a game of morra. And I’d always win. I’d win chocolates or sweets, and then they’d drive me back home in their trucks.

INTERVIEWER

Did you never feel that you were in danger?

CAVALLI

Nothing ever happened to me. The truck drivers behaved perfectly, they were kind—in those days, at least. None of them tried to lay so much as a hand on me. They must have been stunned to see a fifteen-year-old girl asking for a ride to the service station at two in the morning. It was like a dare. Maybe I was just so strange that I brought out some timidity in them.

Those who did try something with me were all people of a different sort—lawyers, my piano teacher, family friends. It was fun sometimes, I liked the perversion of the unfamiliar. It was a kind of power, and I enjoyed exercising that power. I lived in Ancona for two years because of my father’s job, and there—it was incredible—every man tried to touch me. It’s not that I was shocked, but I did think less of them. I was never the victim. I was too full of myself to stand for being the victim.

INTERVIEWER

And you never fell in love with a man back then?

CAVALLI

You could see it from a mile away, my predilection for women. Except for one time, when I got a bit of a crush on my neighbor, a beautiful boy—we’d become friends in a way that was almost erotic. But no, I never fell in love. Mine was also a moral decision. I couldn’t stand being the one who had to submit. I couldn’t stand being told, Well, but he’s the man—in the sense that he was freer than me, stronger than me. I would go crazy. I could never have stayed one step behind, been less important than a man. I’ve made love with so many women who’ve been disappointed by their men. And I used every experience of falling in love, every one of my body’s sensations, to write my poems. I don’t have a soul, I have only feelings and words.

INTERVIEWER

Have you always written in the same way?

CAVALLI

Of course not. For a while, until I left Todi in the sixties, I thought that writing poetry meant changing words a little. I invented words, truncated them and made them mysterious, and I wrote things that meant nothing, absolutely nothing. I was unhappy, even in my writing—I was fake. But I never stopped writing.

Then one day I announced that I was going to Rome, and I went, to a rented room near Termini Station. I didn’t know anyone, didn’t have a watch, couldn’t get my bearings. I’d stand on the sidewalk with one hand in my pocket and I wouldn’t ask anyone for directions because I didn’t want to seem like a tourist. Every month I’d spend all the money I had right away because I was always taking taxis, so then I’d have to go back to Todi. All I had was this group of gay American friends, who were elegant and sophisticated. I’d go out with them at night. I was the only woman, and I spoke very little English. I’d ask, So, where are the lesbians? They found me funny. Really, I was depressed and alone.

INTERVIEWER

You once said, “Elsa Morante pulled me out of my unhappiness and made me a poet.”

CAVALLI

In 1969, Elsa Morante had just published The World Saved by Kids. Pier Paolo Pasolini called it “a political manifesto written with the grace of a fable, with humor, with joy.” Once I’d read that book, I was certain that I was like her—but I was just a conformist, still stuck in 1968, while she was already past that, and impatient with my platitudes. In Rome, I finally met her, thanks to a friend of mine who introduced us. But I was too proud, and I arrived late, just as she was leaving. Still, she said, Telephone me if you want. I was a snob then—I pretended I was cool when I wasn’t, pretended I had money though I didn’t—but I did telephone her. I can say with certainty that that’s where everything began for me. I met all my dearest friends thanks to her—critics, editors, historians, actors, artists, set designers. A whole bunch of us would go out to lunch in a pub, some humble, unpretentious spot—this was when she was writing History, so her head was deep in that world—and she was the queen of those lunches. Almost always she’d pay for everyone. Then we’d go have a gelato somewhere. We spoke properly, were careful not to use words that annoyed her. We’d be together from twelve thirty on the dot until four or four thirty, when we’d walk her to her front door, and she’d sit down to write until late into the night.

She was thirty-five years older, but she always treated me as an equal. I took care at first not to mention that I wrote poems—I knew how difficult she could be, how quick to scorn and exclude. For her, poetry was the ultimate, the most important art form. I knew that what I’d written up to that point would have horrified her. I imagined she would say, Aren’t you embarrassed? But one day she stopped short in front of me and said, So you, what do you do? I don’t know how it came to me, this wicked, impulsive idea to say, I write poems. She gave me a sadistic look and said, Oh yes? Well, let me read them—not because I’m interested from a literary standpoint, I just want to see what you’re made of.

It was hell. After that, I went into hiding. I shut myself in at home to rewrite—that is, to write—my poems. It was a kind of spiritual exercise, and the wonderful thing—no, the miraculous thing—is that from this quasi-fraud emerged the truth of my lines. After six months, I brought to the restaurant a little folder of thirty poems, all short. Then I went home. Half an hour later, the phone rang and it was her. I don’t think I’ve ever again in my life been so glad. I had been accepted—no one could kick me out. Now I was a poet. Everything that happened after that seemed natural. Writing, publishing, the reviews—nothing mattered more than the recognition from Elsa Morante. She was the one who chose the title of my collection, My Poems Won’t Change the World.

We argued a lot over the years of our friendship. Actually, we argued right up until the end of her life. By the end, it had become very painful. And then I abandoned her. I can’t say I have any regrets—being with her had become impossible. But that was the crucial meeting of my life.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve published six collections of poetry, but you’ve also translated Shakespeare, Molière, Oscar Wilde. What does the work of translation mean to you?

CAVALLI

I’ve translated The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Othello, and Twelfth Night. I sought to understand the voices Shakespeare wanted to give his characters. I listened to them, imagined them. I tried always to produce living translations, ready for the stage. It’s like verbal gymnastics. You can’t just ferry the words from one language to another, and you can never search for synonyms, which don’t exist, because every word is unique—every word wants to mean exactly that. You even have to imagine the faces of the actors and their voices, an audience applauding, the box office revenue you’ll rake in. That’s the only way for the work to be open and fruitful, the only way for me to speak directly to Shakespeare, to Molière, the only way not to wrong them.

INTERVIEWER

You often personify what you write about. One of the brilliant, labyrinthine essays in Con passi giapponesi is titled “Headache.” Like Joan Didion, who also wrote beautifully on the subject, you treat this painful invader of the head as a companion.

CAVALLI

My headache was almost always preceded by euphoria, and then it would crash into me brutally. When I got the aura, I’d collapse into a visionary state. First comes that uncontrollable happiness—you feel the universe, the continents, the seasons, infancy. I’d start singing in the street. It was irresistible. I wasn’t even embarrassed. I’d start singing operas that didn’t exist … then I’d get emotional, and I’d cry. Maybe it was a kind of lunacy, a primal passion. And then, all of a sudden, boom! As if I’d been struck in the head, that ecstatic experience would become pain, pain, pain. It was a confluence that made me levitate, until it passed and I felt at peace. Then it felt as if there were two of me, because it seemed impossible to have borne such intense pain.

But now he won’t come back, and I miss him. I get bored. The headache was an extraordinary thing—like love, when it lands and shatters everything—and as I said, when it comes to writing, I’m always moved by some ecstatic form of adoration, or contempt, or hate. By something corporeal that possesses me—desire, or a headache. It seems to me, now that I have neither, that I’ve grown duller, dazed, that I don’t feel anything anymore.

INTERVIEWER

You have described this moment as a kind of poetic crisis.

CAVALLI

Writing poems is strange, like being dragged toward something that, before, didn’t exist, that you hadn’t conceived of. Inspiration, for me, was a mode of transport toward a vision that was dictated to me. Now, well, no one’s dictating. I don’t feel the wave. Once in a while you can conceive of some poems mentally, but it’s no good. Especially if you have no memory. There must be an immediate memory, while you’re writing. Writing is a memory, a word-for-word memory. The cancer has caused so many changes in mood and such physical weakness. There are moments when I forget my own feelings. I can only repeat the old ones, like something I know, more or less.

I’ve always written to be loved, but now what? I haven’t been writing beautiful poems. I wake myself up at night, I think of something, and transcribe it. Then I go back to reread what I’ve written, and I think, Are you stupid? Right now, I feel far from poetry. And if I reread my shortest poems, well, I tell myself, often they’re bullshit. So as a result, all I do is self-cannibalize. I take these millions of manuscripts I have and recopy them in nice handwriting. Since they’re also fairly old and I’ve forgotten about them, this gives me a kind of pleasure—discovering that I wrote that thing.

INTERVIEWER

You are also famous for your fantastic dinners, which delight and terrorize your friends.

CAVALLI

Yes, I love—and in this love, too, there is eros—making dinner for my friends. Even now, when I tire so easily. Setting the table with the most beautiful tablecloth, marvelous glasses, flowers arranged just so. My friends are terrified because they know that if they bring wine, the wine has to be only the best. The flowers have to smell good, and not everyone knows how to choose flowers. And not all the guests will be wearing a nice scent—for me, smell is the most developed of my senses, the one that is the source of the most pain. I buy cheese in only one place, marrons glacés in another, breadsticks in another. My dinners are a work of seduction. There was a time when everything came very easily, even soufflés. You know how hard it is to prepare the perfect tomato sauce, to make the perfect spaghetti in tomato sauce? But what I like most is a messy table, after dinner, with the remnants of the meal, the half-empty glasses, the stains on the tablecloth, the crumbs, the pitchers of water, the chairs out of place. I’ll take pictures of the scene.

I need this continuous mise-en-scène. I used to love climbing onto the table to tap dance. I need to perform, to be on the stage, to let my comic side come out, to use my whole body. The voice, the words, the body. The truth is, I wish I had a kind of entourage with me at all times, someone to compliment me, someone else to compliment me again, someone to touch me lovingly. And I’d read a poem, sing a song, fall in love, have fun, let myself be coddled. This is the life that I like and that gives me that bit of happiness I need to write poems.

INTERVIEWER

Although you said that to write poems is to be dragged toward something that previously didn’t exist. A kind of miracle, something beyond the body.

CAVALLI

It’s like that, and it’s also like being dragged toward precision. There are many ways to write poems. The shortest ones are like shards that have broken off from a larger whole. Poetry is the collision of intention and chance. Something needs to fit into something else, but without overwhelming it, in such a way that it seems that everything has to be like this—that the first time you open your mouth, this is the breath that comes out. If you can manage to stay just at the point when the words resonate, where they arrange themselves into a whole that is obvious, necessary, and surprising—then what’s happened is a manmade miracle.

But when I open some book of poetry and my eyes slide along as if over a mirror, and they don’t stop on any word, they keep moving because the words are insignificant and hinder every emotion and you don’t know why they’re there, then I feel as if I’m sliding into a black pool, and I have to close the book right away. And I can never remember who wrote those lines.

INTERVIEWER

When do you write? How do you write?

CAVALLI

I write wherever, at whatever hour, with a pen. Usually, I write on sheets of paper. My house is full of papers, my drawers are overflowing. I’d need a secretary to organize everything.

INTERVIEWER

Geoffrey Brock has written that you “revitalize the traditional techniques.” What’s your technique?

CAVALLI

I wouldn’t say that I have a technique. I’m open to anything so long as the poem sounds a certain way, so long as it resembles an unexpected reality. The sound of a word, which is not an empty sound, produces a wave that has its own duration. I have no preconceptions, nor do I have any preformed forms. I don’t try to make a sonnet. The rhymes have to be almost inadvertent, casual. The most important principle is to leave the words their liberty, as if they were animals on a soft, flexible leash.

INTERVIEWER

Who are your poetic models?

CAVALLI

Contemporary poets, unfortunately, don’t come to mind. What can I do if there’s no one I admire? Maybe it’s a form of rivalry or envy. When you read the real poets, the words come at you, they open themselves up rather than close themselves down. This happens to me with Dante, with Cavalcanti, with Leopardi, with Emily Dickinson, with Sandro Penna. I learn them by heart, they keep me company. I’m walking down the street, or around my house, and at a certain point they come to my rescue. With them, it’s never just the beginning of a poem, it’s more like the beginning of a concerto. I set the poems of Emily Dickinson to music, and when I read them the music comes to me along with the sound of the words. My nature is theatrical, and my poems are inseparable from my voice and from my way of saying them. I don’t recite poems, I say them. Or I sing them.

INTERVIEWER

What is your definition of poetry?

CAVALLI

I studied Greek as well as Latin meter—I have it in my ear. It’s a natural, musical rhythm that has guided me, always. I wouldn’t be able to start writing a poem if I didn’t immediately hear something that sounds—call it a regular rhythm, or stress, the eruption of a line that already has its own form.

But many of the short poems I’ve written are like stories in verse. Rarely could you say of me that I’m a lyric poet. There are some poems that are like songs, but those are few. In my poems, there’s always some visible, solid matter. This is lightened and rendered more delicate by the language, by the rhymes, by the assonances, by how the lines move, how long they are, all things that are natural, and that are also born before the thought—that the thought is chasing after. The idea reveals itself, it inheres in the words that brought it along. It never precedes them.

INTERVIEWER

There is also the familiar furniture of your poetics—the chairs, the pillows, the lamps, the kitchen tiles, the basket of dirty laundry, the brush.

CAVALLI

I love objects, it’s true. In fact, if I think about my death, I almost—almost—feel sadder about the objects than about the people. My eyes will never again rest on that armchair with that fabric. I’ll miss the beauty of vases, of books, of photo albums, of little wooden chairs. I love to listen to music on my record players. I love to look at my piano even when I’m not playing it. No one can move my things, no one can borrow my books.

But against the serenity, against the lightness of these domestic objects, there’s always this contrast, the unpredictability of the body and the environment—it’s a double movement. Right now, this one bathroom at the top of the stairs torments me. It made me fall one night. There’s a feeling inside objects, but above all they contain the memory of feelings—these paper lampshades, these notebooks with their white pages, on which I may never again write.

Translated from the Italian by Miranda Popkey. Introduction translated by Oriana Ullman.

Annalena Benini is an Italian journalist, columnist, and author. She has been writing about books and culture for the daily newspaper Il Foglio since 2001, and currently edits its monthly magazine. In 2021, she received the Premio Viareggio Repaci for journalism.

Read Patrizia Cavalli’s poetry in the archive.

Copyright

© The Paris Review