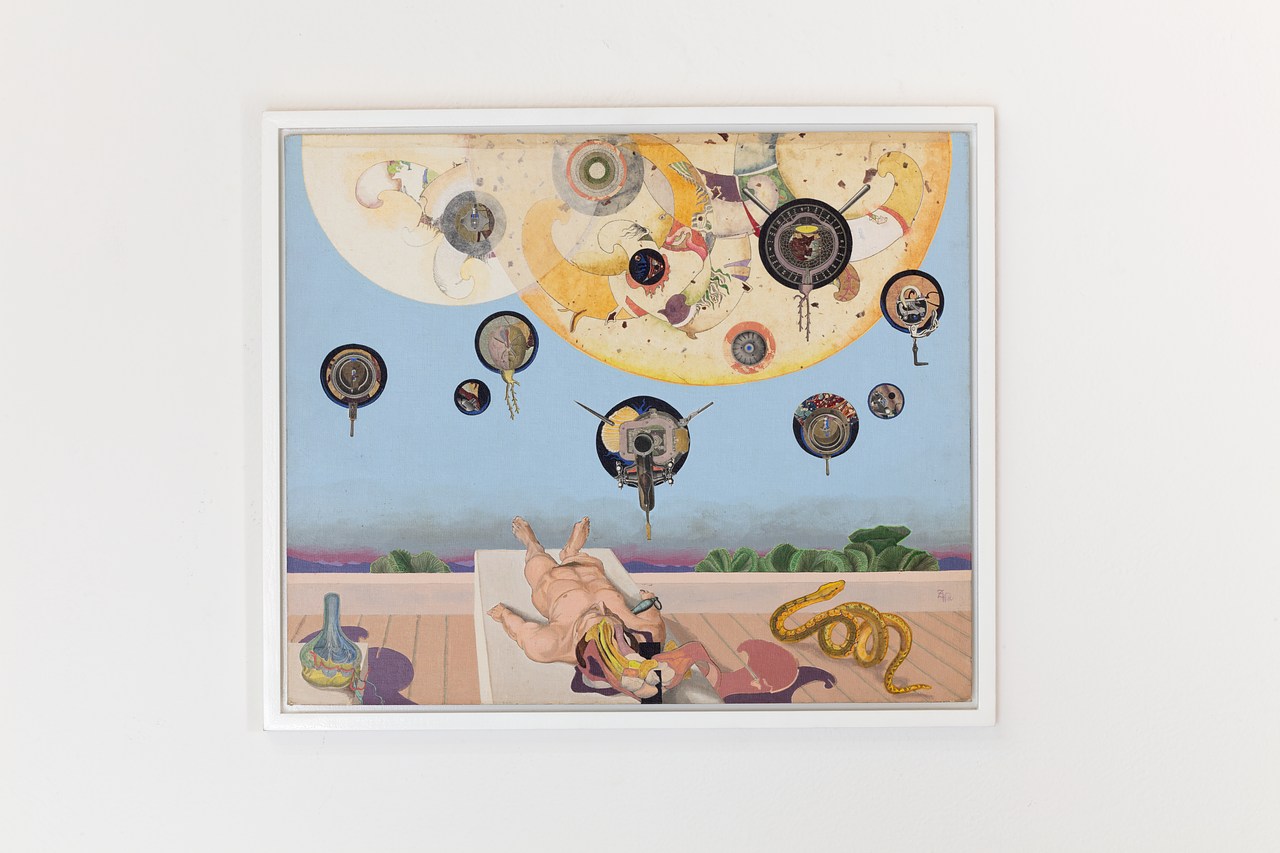

Mural at the Amargosa Opera House. Carol M. Highsmith, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Gia wants to disappear. This is an ordinary desire while in pain. In moments of hardship, it is tempting to admire the ascetic. The imagined glory of solitude is that our inner life will become a source of endless pleasure. Of course, this is fiction. Everyone is touched by loneliness, while alone and in company. To bear it, we must find something from beyond to sustain us. This is what Nicolette Polek’s Bitter Water Opera seeks.

Polek’s debut novel, published last month by Graywolf, shows us the mechanics of a mind negotiating a rupture. It’s easy to say that Bitter Water Opera is about a breakup, but that would be a narrow view. As in real life, the relationship comes undone downstream from a more preeminent but obscured event in the emotional life of one or both parties. Gia’s relationship seems fine. It is sparsely characterized, mostly through memories of excursions dotted with palms and bougainvillea. But for Gia, this pleasantness is intolerable. She starts acting erratically, flirting with strangers. Soon after, she leaves both him and her post in a university film department. Her mental state is vague, made up of a loose association of memories, summoning trinket-like facts, like “the prevalent tone in nature is the key of E.” She has traded a life in exchange for something she has not yet learned to want. But what is to be done when desire turns its cheek to you? What is there to want when you’ve stopped wanting what you wanted? In the absence of wanting, it is helpful to find a human example to follow, try to insinuate yourself in their map of desire and its attendant habits.

Through the figure of the dancer and choreographer Marta Becket, Gia tries to summon a model for a life she could find agreeable. “Marta got through without needing, grieving, or waiting on someone, and now, after death, I was her witness, hoping that she, in some act of imitation on my part, could fix my life.” Becket was a real woman who abandoned her life as a ballerina in New York in favor of the oblivion of Death Valley, where she dedicated herself to running a previously abandoned recreation hall to showcase her one-woman plays and ballets. At the Amargosa Opera House, Becket performed her own choreography for nearly fifty years. In the early days, her only audience members were the faces of heroes and loved ones that she had painted into the trompe l’oeil mezzanines, from which they permanently applauded. Her husband, Polek writes, was off with the prostitutes in town, trying to withstand the fact that Marta did not need him. Eventually she became a cult figure, luring crowds, the press, and lost women like Gia into her orbit, even after death.

After Gia writes her a letter, the ghost of Marta enters Gia’s life, and with her a flurry of activity. The pair have full days together: painting, picknicking, hiking. For a while Gia pantomimes Marta’s actions, but it soon becomes evident that she is not yet ready to stand up to the task of living (she attempts to get back together with her ex-boyfriend). The ghost of Marta exits, taking her watercolors with her. Gia descends into catatonia. Towards the middle of the novel, Gia looks out over the pond outside a house in the country where she’s staying alone and sees the floating corpse of a dead deer. This visceral encounter with a rotting animal draws Gia out of the misty, desultory realm she has lived in for so long and forces her to contend with the bare facts of nature, and the nature of herself: she does not live the life of an embodied subject. Her central problem is her tendency for “limerence,” as she calls it, which leaves her chronically unable to connect with the present. But this insight is brief, and an epiphany does not cohere. “The smell faded for good, and with it my revelation.” Here she is confronted with the mystery of herself: something has peeked out from the curtain behind which her mind stages a secret play. It is a glimpse at something that will eventually be revealed in full, but she must wait. Insight tends to come soon after we are emptied out completely. As the epigraph notes, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Copyright

© The Paris Review