Walton Ford, Culpabilis, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York. Photograph by Charlie Rubin.

I touch down at Marco Polo on Wednesday afternoon, one among the many who have come for the preopening days of the Venice Biennale. The airport—with its series of moving walkways shepherding passengers toward the dock—will turn out to be the only place in the city where I manage not to get lost. The line for the water-bus into the city is easy to spot, and as we wait for the next boat to arrive I count fifteen Rimowas, five pairs of Tabis, and several head-to-toe outfits of Issey Miyake. The boat ride, unaccountably, takes an hour. I alternate between fending off seasickness and watching the Instagram Story of a microinfluencer who’d been on my flight and is already flying down the Grand Canal in a private water taxi.

My first stop after depositing my bags and downing two espresso is Walton Ford’s Lion of God. The show takes up the two full stories of a church-like building in the same square as the city’s opera house, which my boyfriend is telling me—with the sort of walleyed zeal that suggests it’s one of a handful of facts he memorized for the trip—burned down in the nineties. Inside, it’s surprisingly dark, the main floor cut up by temporary exhibit walls painted black, the lights so dim that the details of the building, and the historic paintings spanning the rest of the room, are almost completely obscured.

In other words, you have no choice but to turn your attention to Ford’s four enormous watercolors, which, despite the best of intentions, strike me immediately as somehow “dorm room.” Maybe it’s the richness of their color set against the black of the room, but I momentarily perceive these objectively impressive works (at least on a technical level) as velvet paintings. The subject is always the same—a lion with a skull in its mouth; a lion with a book in its mouth; a pentaptych of a thorn-impaled paw. Each painting seems to be a different scene from one unified narrative. It’s something biblical, clearly, and the name Jerome pops into my head, along with the fact that Venetian iconography is clearly lion-obsessed, but I can’t quite fit everything together.

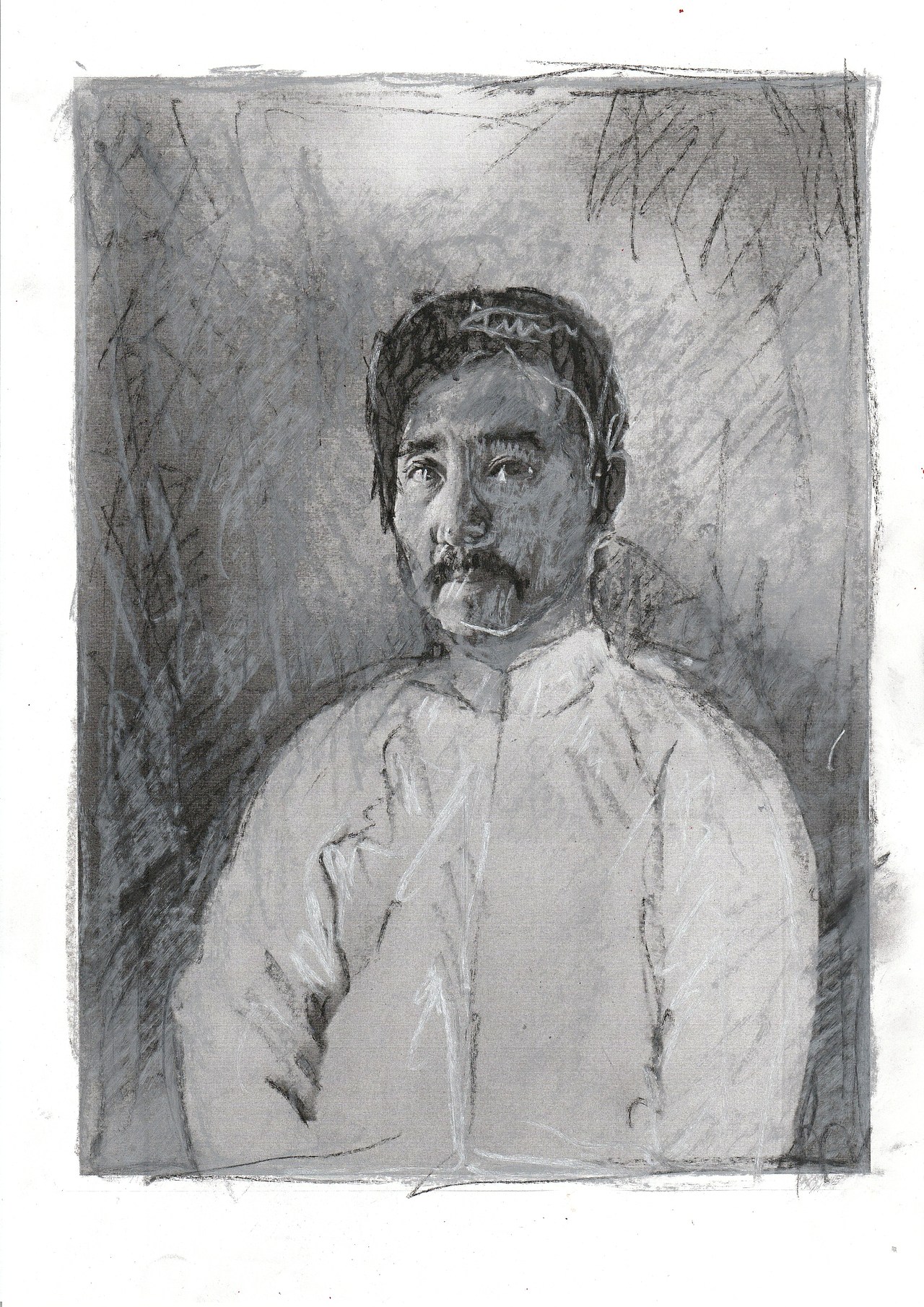

Upstairs, a giant Tintoretto has been moved into the space specifically for the exhibit. It takes up the central wall, and shows Saint Jerome (I was right!) in a state of ecstasy as Mary descends from heaven. I stand before it, a sophisticated-looking group nearby. As it turns out, Ford himself is in attendance, and he strikes up a conversation with one of the women in the group. “I saw you looking at this one,” he says. He points out a faint, shadowed lion in the painting’s bottom right corner, which I’d failed to see, then gestures to the perimeter of the ceiling, where a few paintings have been carefully spotlit, highlighting the animals often buried in otherwise busy canvases. “I thought, what if you took all the people out,” Ford says, “and focused on the animals?”