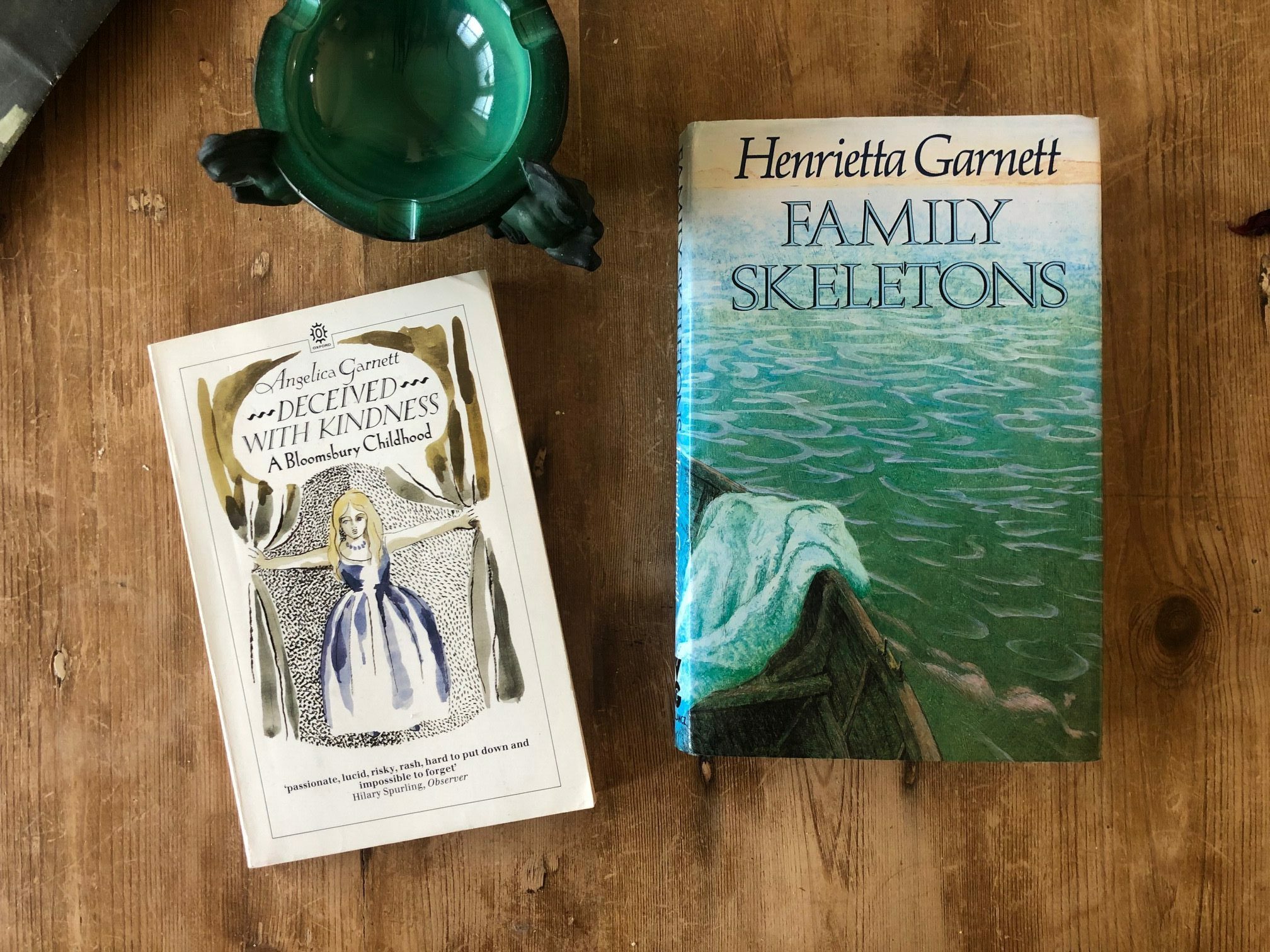

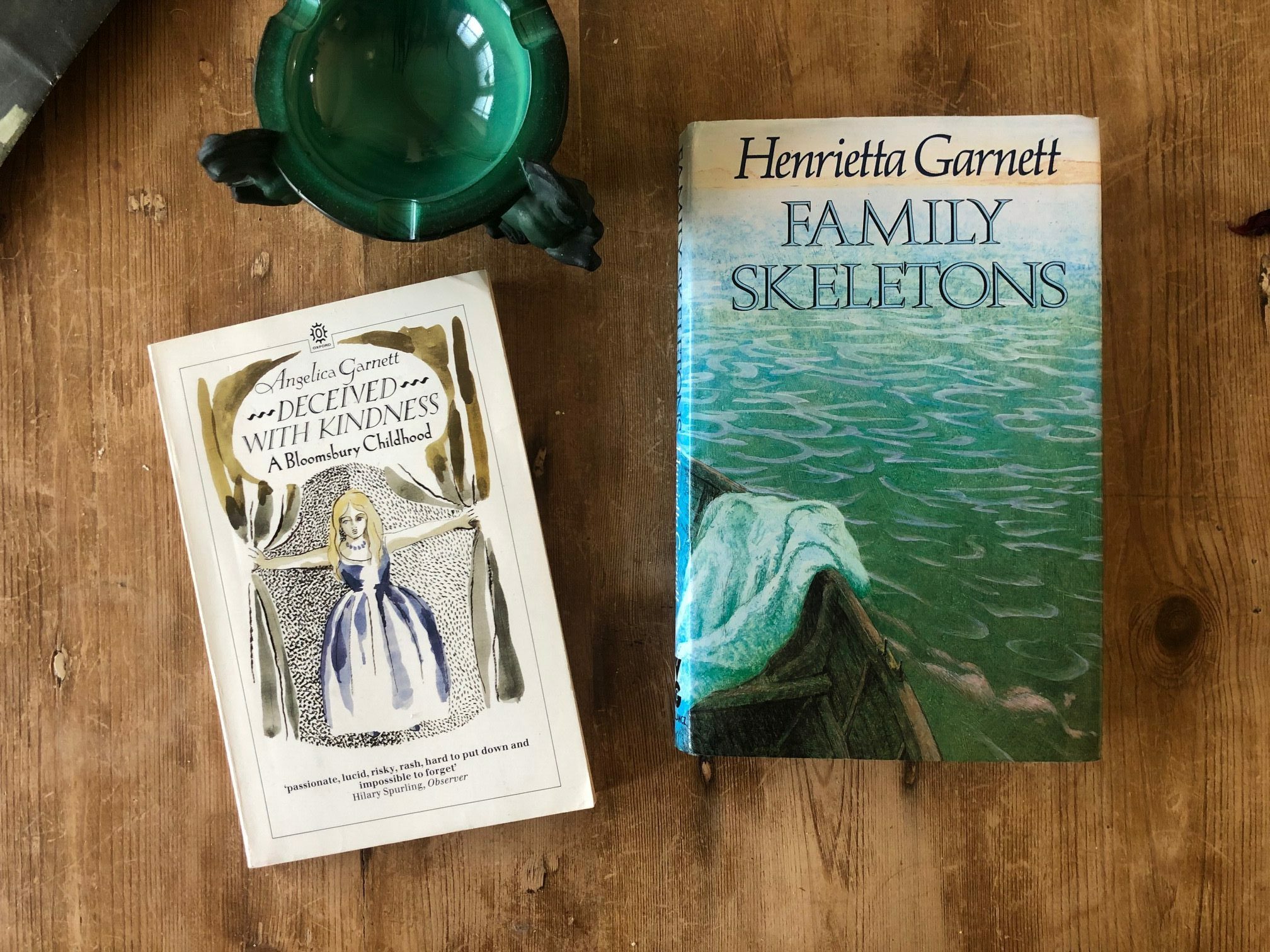

Henrietta Garnett was forty-one when her first and last novel, Family Skeletons, was published in 1986. She knew that her debut, a tragic gothic romance revolving around a complex constellation of family secrets, would face an unusual degree of public scrutiny: Henrietta was English literary royalty, the direct descendant of the Bloomsbury Group on both sides of her family tree. Her father was the novelist David “Bunny” Garnett, author of the James Tait Black Memorial Prize–winning Lady into Fox (1922), a book so highly regarded it was on the British high school syllabus when his daughter was a teenager in the late fifties and early sixties. Henrietta’s mother was Angelica Garnett, née Bell, daughter of Virginia Woolf’s sister, the painter Vanessa Bell. “I had been putting off trying to get anything published,” Henrietta confessed when an interviewer asked about her famous relations, “because I couldn’t help thinking that whatever I did it would never be as good as anything they’ve achieved.” Family Skeletons is a strange and singular creation: melodramatic in plot but elegant in tone, written in a cool and fluent prose that is utterly Henrietta’s own. The novel bears no resemblance to either Bunny’s or Woolf’s fiction; nevertheless, the story does contain more psychological traces of her family’s legacy—namely, of the uniquely disturbing personal dramas that shaped the lives of those who raised her and the public perception of the Bloomsbury Group.

***

Family Skeletons begins at Malabay, a grand old house in the wilds of Ireland. Our first glimpse of the rambling lakeside estate is early one summer morning: “The dew was heavy and glittered on every twig and leaf and blade of grass. The rain, so fine that it seemed to be suspended in the misty air, shone like the frail skein of a cobweb. The air was so moist, the leaves and grass so wet, the fish pond and the lake so scheming with reflections, that the division between land and sky seemed nebulous, amorphous and indistinct.” It’s a place that “gets into the blood” of those who live there. Ever since the death of her parents, seventeen-year-old Catherine has been raised at Malabay by her uncle Pake, a taciturn recluse still haunted by the torture he endured as a prisoner of war years earlier. Barring the household staff—Mick-The-Post and her cousin Tara, the only visitor Pake will allow—Catherine is completely shut off from the rest of the world. She measures out her days by riding her beloved horses, writing fanciful stories, and attending to the rather unconventional curriculum her uncle has devised for her education (translating the ancient Greeks features heavily). Given her naïveté, it comes as no surprise that she is in love with the handsome, older, and more world-wise Tara. That he returns her girlish affection is perhaps a tad less convincing, but it befits the almost mythic structures that organize this slightly off-kilter world. This incestuous undertone, which foreshadows certain revelations to come, is just one of a handful of nods to Wuthering Heights (1847). Although less headstrong than her nineteenth-century namesake, Henrietta’s Catherine is another skittish beauty, frequently compared to the animals she so adores. When Pake discovers that the cousins plan to marry, he explodes in a rage—but the lovers put this anger down to his general eccentricity and proceed regardless. Only three weeks after their wedding, in a traumatic reprise of her parents’ deaths by drowning years earlier, Tara is killed in a boating accident out on the lake. The teenage orphan, now a widow, is distraught; she lops off her hair, takes to her bed, and descends into a “wild and desperate misery.”