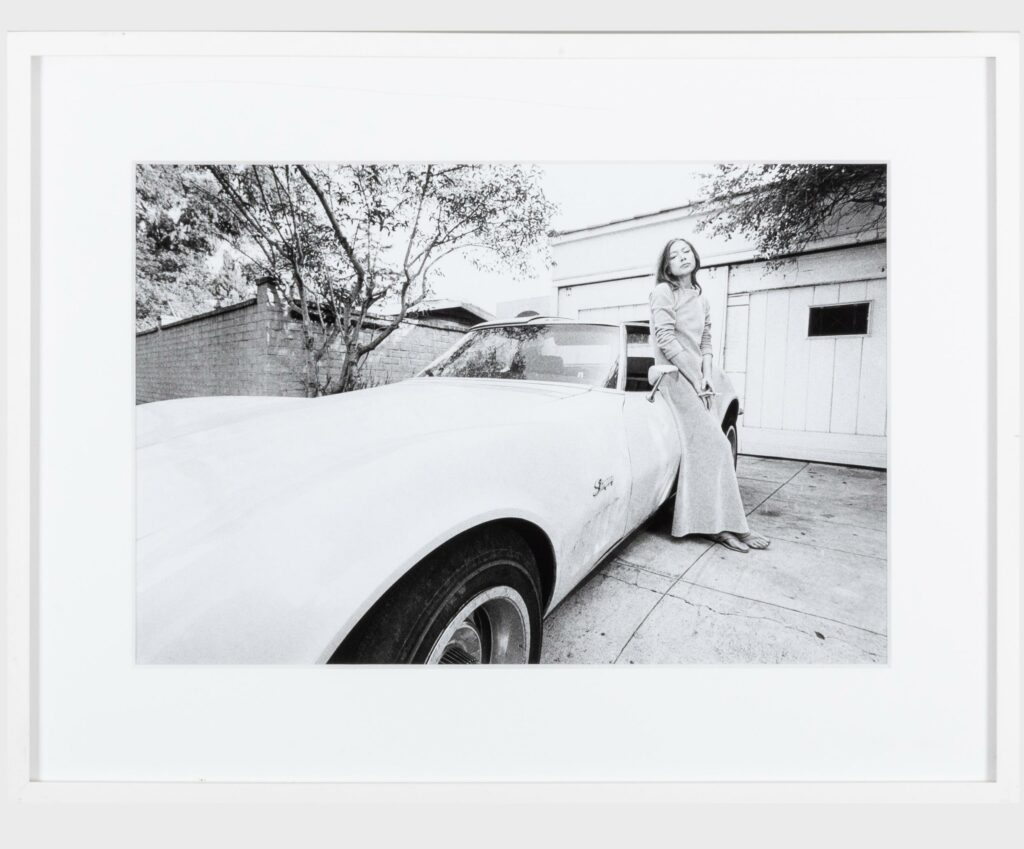

Joan Didion with her stingray corvette, Julian Wasser. Courtesy of Stair Galleries.

In November, writers began making little pilgrimages from New York City to Hudson to see Joan Didion’s things. In fact, thousands of people came to Stair Galleries, an auction house on the main drag of a town filled with antiques stores, farm-to-table restaurants, coffee shops, and stores that all seemed to be selling only five items of clothing. I made my own journey by early-morning train. Didion died this past December at eighty-seven, and a selection of her furnishings, art, books, and other things was being auctioned at an estate sale, with proceeds going to Parkinson’s research and the Sacramento Historical Society; prior to the sale, a small exhibition was open to the public, titled “An American Icon: Property from the Collection of Joan Didion.”

The word icon is fitting and perhaps inadvertently implies the way some people become like relics in life and especially in death. Didion certainly became one, via the mythology and imagery that became attached to her—who hasn’t seen that photo of her posed on the white Corvette, or in the black turtleneck, and marveled at her ineffable cool? (Both photographs were for sale.) She came, through her work but more so through her persona, to symbolize something, or a whole set of different and sometimes contradictory somethings, about being a writer, a woman, and a person of certain class at a certain time in America. And now here were her actual relics, the things that outlasted her, which might serve as little metonymies for whatever it was we tried to read into her.

The exhibition was neatly siloed into two small rooms, but it really was quite a lot of stuff, actually a quantifiable number of things (224). It was set up like an artificial apartment where Joan might have been caught in medias res for a glossy magazine spread—couches arranged around a coffee table with a cashmere blanket thrown over one of them, desks with typewriters on them, artfully stacked art books. Her books were organized into coherent sets, which would be sold that way in lots: Didion’s Hemingway, her Graham Greene, her California cookbooks, a mishmash of political nonfiction like Uncovering Clinton: A Reporter’s Story and Bush at War that one might have bought in an airport in 2002. Many of these books possessed a pleasant, weather-beaten quality, their jackets faded like they were abandoned on the patio of a Cape Cod summerhouse. There was something of a shrine constructed to California Joan, with five books about California placed around a photo of her in a straw hat, among the palm trees. Along one wall, there was large glass cabinet full of her dishware, her pots, her glasses, all the small personal odds and ends that we scavenged through. Everything had a tag stating an estimated price, all of which were quite obviously lowballs.

The press had been here before me and would come after me, all of us writing lists of her things and descriptions in little notebooks and taking pictures we couldn’t resist posting online. (Taking stock of her belongings like this reminds me of seeing Didion’s perennially Instagrammed and impossibly chic packing list, which includes “2 skirts, 2 jerseys or leotards…cigarettes, bourbon.”) Why were we here? Did we want to know if Didion had good taste? The answer to that question was mostly yes, or at least that she had the good taste of a specific milieu, that of a California WASP in the latter part of the last century: Le Creuset cookware, heavy gilt mirrors, Loro Piana cashmere, monogrammed napkins, a rattan chair, a bamboo-and-lacquer side table. There was plenty to covet, though there was also plenty one wouldn’t want—hefty, overwrought silverware, the kind one used to inherit and still might, and some really appalling watercolors. I am always struck by how things that feel like they belong in a particular time and place insist on lasting, lasting past the person who assembled them and made them into a life.