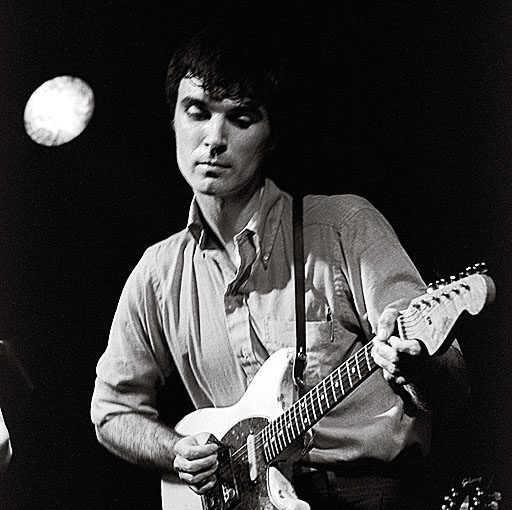

Matt Berninger. Wikimedia Commons, Licensed under CCO 2.0.

This week, the Review is publishing a series of short reflections on love songs, broadly defined.

In her 1993 memoir Exteriors, drawn from seven years of journal entries, Annie Ernaux describes overhearing a familiar pop song at the supermarket. She is struck by the pleasure she experiences—and by a “feeling of panic that the song will end.” This prompts her to consider the relative emotional effects of books and music. While certain novels have left a “violent impression” on her being, the impact hardly compares to the “intense, almost painful” feeling produced by the song. “A book offers more deliverance, more escape, more fulfillment of desire,” she writes. “In songs one remains locked in desire.” The structure of pop music is inherently erotic; the repetitions of rhythm and melody continually summon and satisfy aching anticipation. Love songs bring this otherwise sublimated longing to the surface: some through grand, theatrical gestures, others by drawing out the dialectic of desire embedded in everyday life—say, the feeling of being alone at a party, sad and self-conscious, desperately missing someone.

This is the premise of “Slow Show,” a somber but rousing midtempo track from The National’s 2007 album Boxer. The narrator spends the verses separated from his lover, surrounded by people but unable to reach them, confined to the claustrophobic quarters of his own mind. Guitars flutter frenetically over foreboding squalls of feedback, while Matt Berninger’s mumbling baritone evokes the narrator’s recursive, dead-end thoughts: “Standing at the punch table, swallowing punch”; “I leaned on the wall, the wall leaned away”; “I better get my shit together, better gather my shit in.” In the choruses, an atmospheric sweetness swells as he briefly spans the distance, if only in his imagination: “I want to hurry home to you,” Berninger croons, “put on a slow, dumb show for you and crack you up / so you can put a blue ribbon on my brain.” His halting syntax smooths out into the simple, fluid choreography of a fantasized intimacy, which disrupts his anxious solitude.

But even the utopic space of the chorus is marred by doubt in its final lines: “God, I’m very, very frightened / I’ll overdo it.” The same fear that strands the narrator alone in the midst of a party gnaws at the edges of his reverie, manifesting now as a terror of spoiling the moment. (In the roiling “Conversation 16,” released a few years after, Berninger intensifies this same dread: “I was afraid I’d eat your brains / ‘cause I’m evil.”) Within each gesture of mutual understanding between lovers there lurks the possibility that the bond might break; the separation that shapes desire shadows every tender encounter.

Copyright

© The Paris Review