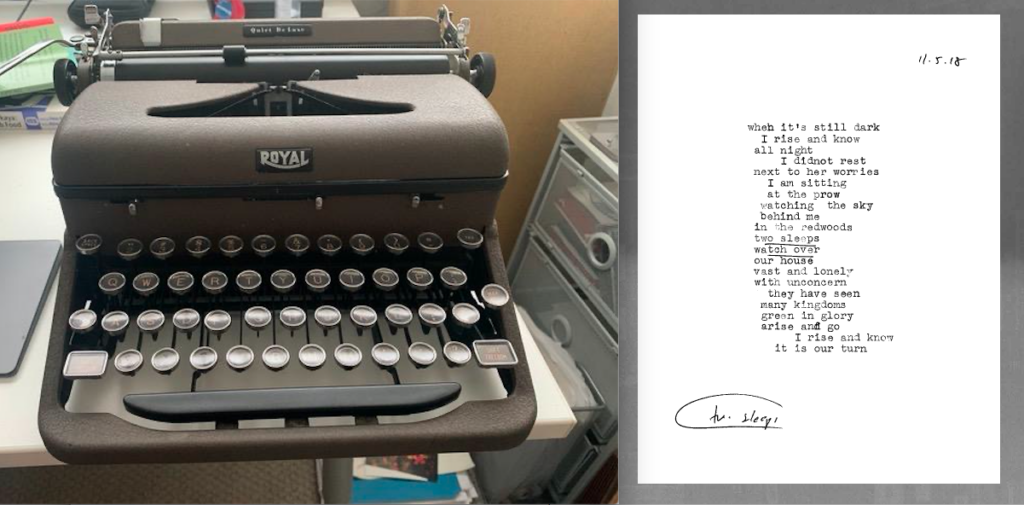

Matthew Zapruder’s Royal Quiet Deluxe typewriter and a typewritten draft of a 2018 poem. Photographs courtesy of Zapruder.

When I was in my twenties, my grandparents finally moved out of the house my mother had grown up in. In the attic where we used to sleep as kids, and where my grandfather would come in at bedtime and sing “Goodnight, Irene” to me and my younger brother and sister as we lay in a row in our little cots, I had found my mother’s typewriter, a Royal Quiet Deluxe, perfectly preserved from her high school days. My grandfather was the sort of person who would make sure it was in pristine working order, and when I opened the case, the keys gleamed. It didn’t even need a new ribbon. It made a satisfying, well-oiled clack.

I lugged it to the house I was living in on School Street, in Northampton, Massachusetts. I had moved from California back to the same weird little valley where I had gone to college, to go to graduate school for poetry. Thankfully I did not yet know that a manual typewriter was a writerly cliché. For a while, the typewriter just sat there in the corner of my room.

I was still toiling away, writing a lot of poems the way I used to: choose a subject, and try to write something “about” it. Use a computer. Those poems always felt labored and ponderous. No matter what I said, the thoughts in them were never new. Nothing was being added by my writing. I had already figured it out, and mostly it was banal and obvious. Death is sad. The city, if you have not been informed, is lonely at night. In it, other people are mysteriously uninterested in me, which is sad and lonely for me, and for them, whether or not they know it.

Occasionally I would try to let things go completely, and exert as little control as possible over the language. Those poems were a mess, and I would stare at them afterward with bored incomprehension.