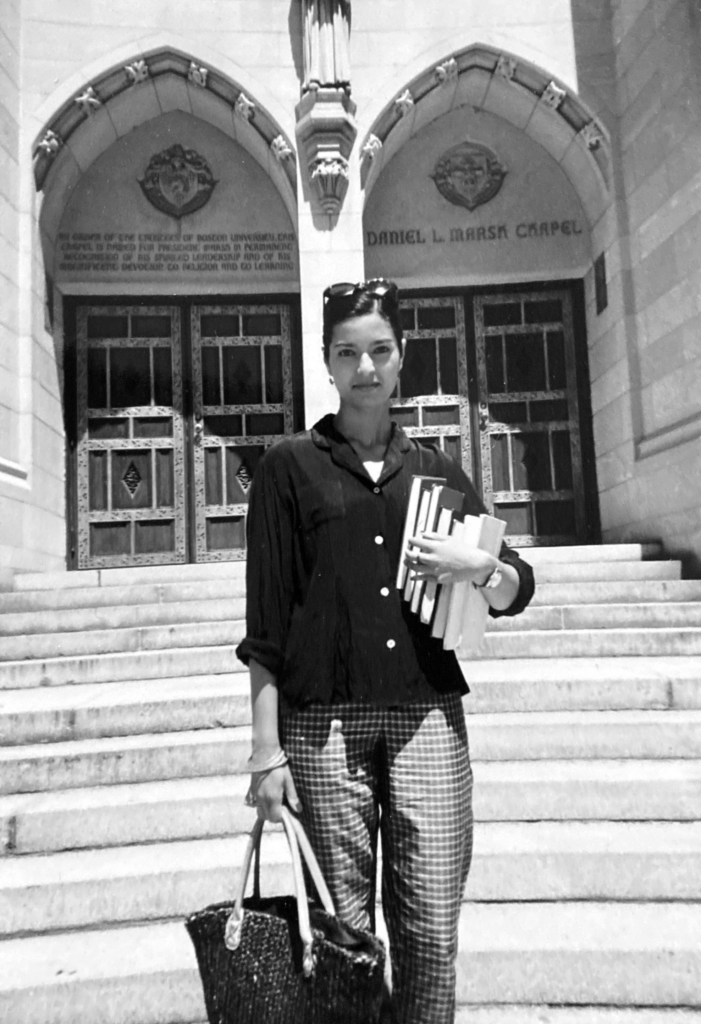

Hebe Uhart. Photograph by Agustina Fernández.

Hebe Uhart had a unique way of looking—a power of observation that was streaked with humor, but which above all spoke to her tremendous curiosity. Uhart, a prolific Argentine writer of novels, short stories, and travel logs, died in 2018. “In the last years of her life, Hebe Uhart read as much fiction as nonfiction, but she preferred writing crónicas, she used to say, because she felt that what the world had to offer was more interesting than her own experience or imagination,” writes Mariana Enríquez in an introduction to a newly translated volume of these crónicas, which will be published in May by Archipelago Books. At the Review, where we published one of Uhart’s short stories posthumously in 2019, we will be publishing a series of these crónicas in the coming months. Read the first in the series here.

When I used to take walks along Bulnes Street and Santa Fe Avenue, a certain boutique would catch my eye. It always displayed the same series of colors: beige, dusty rose, baby blue—a small array of colors, and always the same ones on rotation, never a red or a yellow. Everything behind the display window was elegant but hidden in shadows; this included the owner, who seemed determined to fulfill her duties despite having so few customers. The owner’s silent manner and desire to pass incognito (as if showing one’s face were distasteful) led me, in one way or another, to this idea: she must have inherited her taste in clothing from her mother, and she was making sure to carry on its legacy. Well done, well done on that display window, but with so few customers, the shop was doomed.

On Corrientes Avenue, at the corner of Salguero, there is another window displaying sweaters paired with little vests (for when it gets chilly). Every week, the owners debut a new line of muted colors: grayish blue, blush, timid yellow. Delicate T-shirts that seem to say: This is the way things are. The garments are always the same shape and length; every week, the owners change the color scheme. It occurs to me that this taste is also inherited, passed down from a time when women dressed to please rather than to offend and when dialogues unfolded like this:

“Go ahead, dear.”

Copyright

© The Paris Review