Evert Collier, Vanitas – Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull, 1663, oil on panel. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Read an excerpt from The Book Against Death on the Paris Review Daily here.

Quixotic is a word that comes to mind when thinking of Elias Canetti, not just because Cervantes’s novel was his favorite novel but because Canetti, too, was a man from La Mancha. His paternal family hailed from Cañete, a Moorish-fortified village in modern-day Cuenca Province, Castile-La Mancha, from which they were scattered in the mass expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Having fared better under Muslim rule than Catholic, the Cañetes passed through Italy, where their name was re-spelled, and settled in Adrianople—today’s Edirne, Turkey, near the Greek and Bulgarian borders—before moving on to Rusçuk, known in Bulgarian as Ruse, a port town on the Danube whose thriving Sephardic colony supported itself by trading between two empires, the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian.

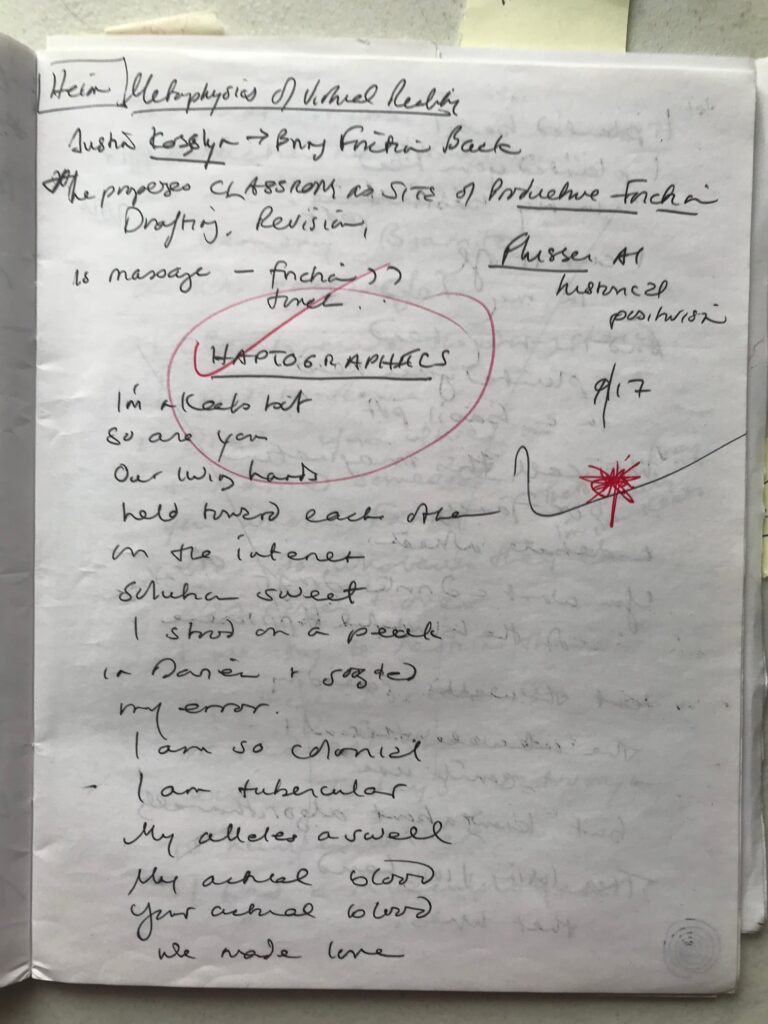

Elias, the first of three boys, was born to Jacques Canetti and Mathilde Arditti in Ruse in 1905 and in childhood was whisked away to Manchester, UK, where Jacques took over the local office of the import-export firm established by Mathilde’s brothers. In 1912, a year after the family’s arrival in England, Jacques died suddenly of a heart attack, and Mathilde took her brood via Lausanne to Vienna and then, in 1916, in the midst of the First World War, to neutral Zurich. It was in Vienna that Canetti acquired, or was acquired by, the German language, which would become his primary language, though it was already his fifth, after—in chronological order—Ladino, Bulgarian, English, and French. Following a haphazard education in Zurich, Frankfurt, and Berlin, Canetti returned to Vienna to study chemistry and medicine but spent most of his energies on literature, especially on writing plays that were never produced, though he often read them aloud, doing all the voices. At the time, his primary influence was journalistic—the feuilletons of Karl Kraus—which might have been a way of giving himself the necessary distance from the German-language novels of the Viennese generation preceding his own, the doorstops of Hermann Broch and Robert Musil, both of whom were known to him personally. His own contribution to fiction—his sole contribution to that quixotic art—came in 1935 with Die Blendung (The blinding), which concerns a Viennese bibliophile and Sinologist who winds up being immolated along with his library. Die Blendung was translated into English as Auto da Fé—a preferred punishment of the Inquisition—though Elias’s original suggestion for the English-language title was Holocaust. In nearly all the brief biographical notes on Canetti, this is where the break comes: when he abandons the theater, publishes his only fiction, and escapes the Nazis by leaving the continent. Exile brought him to England again, and to nonfiction, specifically to Masse und Macht (Crowds and Power), a study of “the crowd,” be that in the form of an audience, a protest movement or political demonstration, or a rowdy group threatening to riot—any assemblage in which constituent individuality has been dissolved and re-bonded into a mass, as in the chemical reactions in which Canetti was schooled, or as in the atomic reactions that threaten planetary existence. Canetti’s singular study of collective behavior, published in 1960, stands at the center of his corpus, along with his remarkable series of memoirs, each named for a single sense: The Tongue Set Free, The Torch in My Ear, The Play of the Eyes. Five volumes were projected, but the series went unfinished: no volume connected to smell or touch was ever completed, and the final year of his life covered in the memoirs is 1937, the year Canetti’s mother died and he began to conceive of a book “against” death, a version of which—the only available version of which—can be found on the pages that follow.