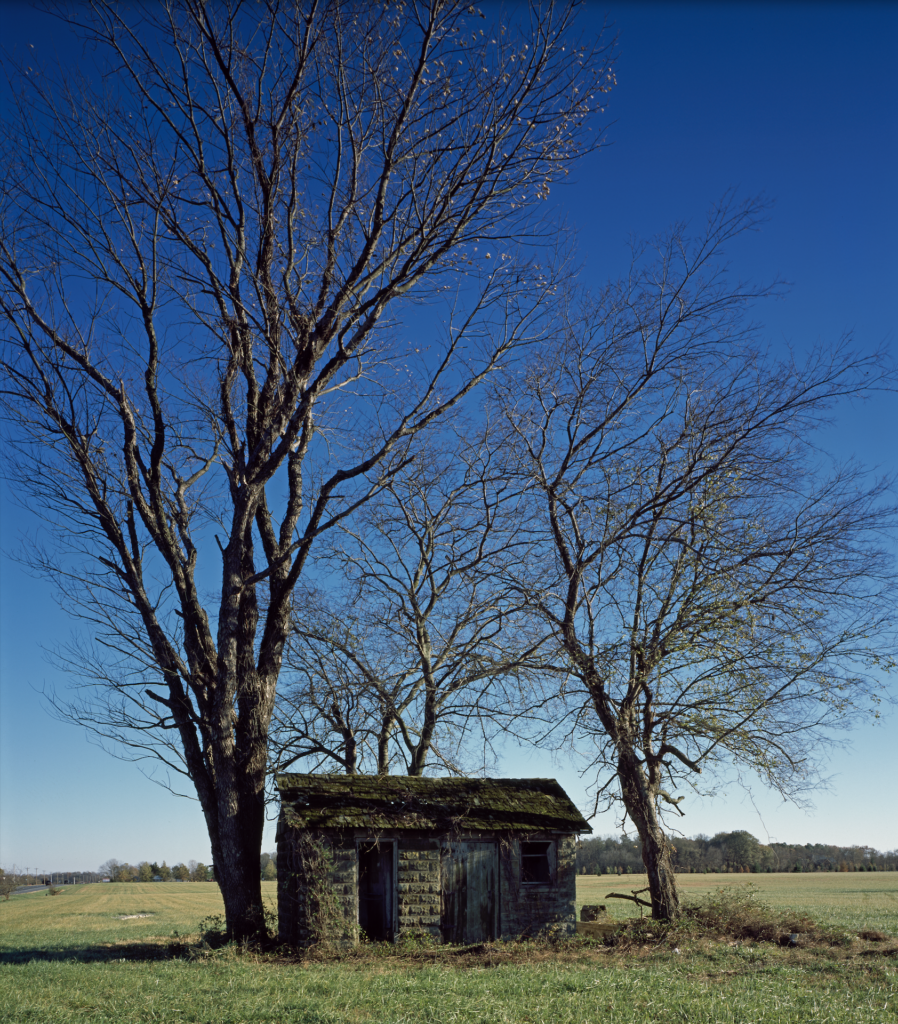

Abandoned shack in rural North Carolina. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

The quantity and quality of consternation caused me by the publication of Alec Wilkinson’s Moonshine in 1985 is difficult to articulate. This utterance should prove probative. If we are in a foreword, an afterword, or perhaps ideally a middleword, we will shortly be in a model of muddle at the very end of the clarity spectrum away from Moonshine itself, with its amber lucidity, as someone said of the prose of someone, sometime, maybe of Beckett, maybe of Virgil, who knows, throw it into the muddle. The consternation caused me by this book is even starker next to the delight of reading the book itself before the personal accidents of my response are figured in. I will essay to detail those accidents, but I would like to first say something about the method of the writing.

Alec Wilkinson is one of two literary grandsons of Joseph Mitchell, the grandfather of the poetry of fact. “The poetry of fact” is a phrase I momentarily fancied I coined, but the second literary grandson of Joseph Mitchell, Ian Frazier, corrected me, and I have assented to his claim that he coined the phrase. One’s vanities are silly and dangerous. It is a vanity to think to say there are but two grandsons of Joseph Mitchell as well. There are doubtless dozens and, of course, granddaughters, too; what I mean is that Alec Wilkinson and Ian Frazier are the grandsons with whom I am most familiar, and most fond, and so it is convenient to sloppily say they are it.

What is the poetry of fact? Good question. Since I am not the coiner of the term and, at best, a dilettante in its practice, I may be excused, I hope, if my answer is wanting, but I vow to do my best. I, alas, have brought it up. When the justice of the peace who conducted my marriage, Judge Leonard Hentz of Sealy, Texas, asked if anyone objected to the imminent union, he looked up and said, of our sole witness, “Well, hell, he’s the only one here, and y’all brought him, so let’s get on with it.”

The poetry of fact is the ordering for power of empirical facts, historical facts, narrative elements, objects, dialogues, clauses, phrases, words—it is the construction of catalogues of things large or small into arrays of power. The power of the utterance is the point. The preferred mode of delivery is the declarative sentence, simple or compound, without subordination or dependent clauses—without what Mr. Frazier has called “riders.” Power in this instance—in any writing, really—is to be understood as a function of where things are placed. The end of a series or sequence or catalogue or paragraph or chapter or essay or book is the position of what we will call primary thrust. It is what will linger in the brain uppermost because it is lattermost. The beginning of an array, large or small, is the position of secondary thrust: the “first impression” that gets lost but never quite recedes. The middle of an array is the tertiary thrust—the middle gets lost in the middle, ordinarily. This is the middle’s job. Games can be played with these positions of emphasis. A sockdolager, to employ Twain, can be buried in the middle where, because it is a sockdolager, it is not exactly buried and may constitute a surprise. The emphatic middle, let us call it, installs an irony, raises an eyebrow whether anyone realizes it or not. An “unemphatic” end also installs an eyebrow. Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style is onto but the very tip of this iceberg with its Elementary Principles of Composition #18: “Place the emphatic words of a sentence at the end.” Were it “The words at the end of a sentence are emphatic,” they’d have been closer to the nuanced complexity of the poetry of fact, but let’s move on.

Copyright

© The Paris Review