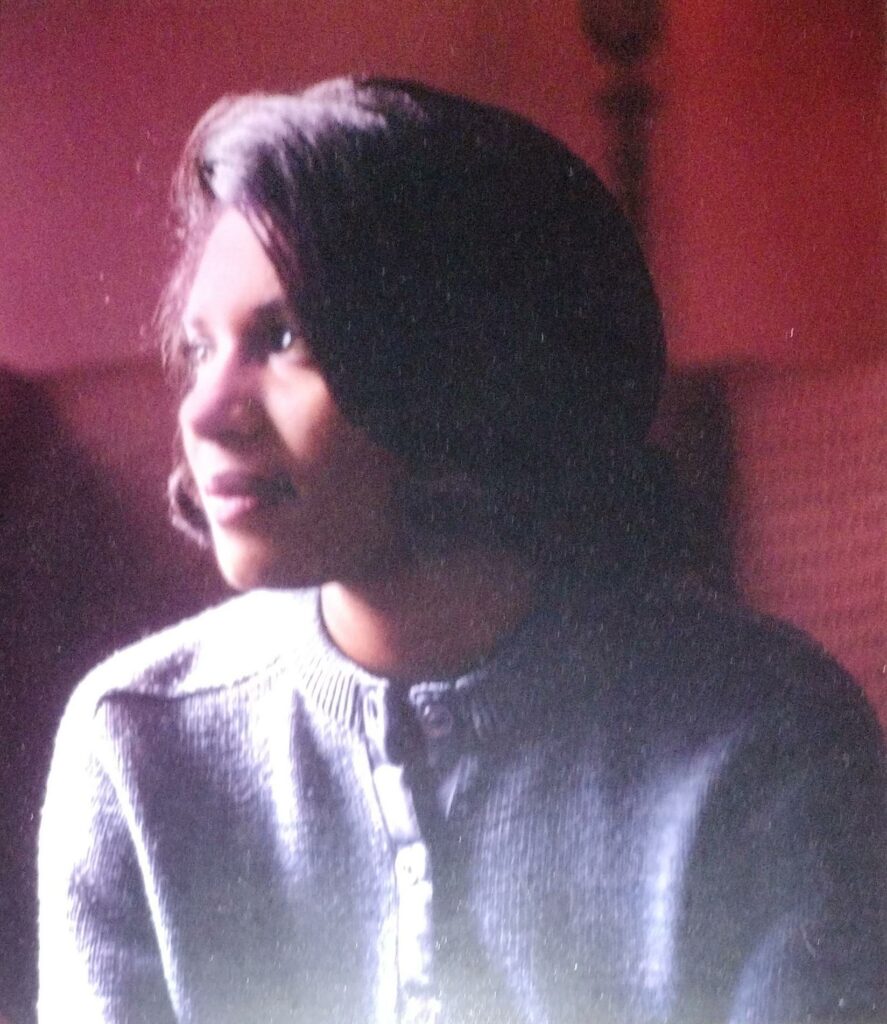

Photograph by Emmeline Clein.

Besides Britney, bottled water is Kentwood’s biggest export. Across most of Louisiana, this town is more famous for the water than the woman. “Why are you going to the water bottle town?” the man sitting next to me at the bar asks. I’m in New Orleans, on Carondelet Street.

I’m eating at an oyster counter near my grandfather’s former office. Not his favorite, the Black Pearl, where he used to eat a dozen daily on his lunch breaks, grading each one on a scale of 1–10 in his notebook. He died at the start of spring this year, smack in the middle of Carnival, the ambulance stuck in parade traffic for an hour. When I tell the man next to me I’m going to Britney Spears’s hometown to see her house, he says he saw her perform before she became Britney Spears, when she was still Britney from Kentwood, at a concert called Louisiana Jukebox. She was there with her mother, answering audience questions after the show. A childhood friend of my mother’s was there, too, and had incidentally emailed me about it the night before. It was disturbing, she remembered; Britney was so young, but her “song was so sexual, and in person, she looked like the girl next door who every man wants to devirginize.”

The next morning, the drive through St. John the Baptist Parish is mostly swamp. Highways on thick stilts through the cypress glens; the long, low bridge over Lake Pontchartrain. Two men fishing, smoking, laughing. Once you cross into Tangipahoa Parish, you’re mostly on dry land, which means Bible billboards and fast-food spots.

On the off-ramp into town, I see the water tower emblazoned with the Kentwood logo, familiar from plastic bottles. I drive down the town’s main street, past buildings with drooping awnings and wilting, cantilevered roofs, an abandoned white brick structure that reads “Kentwood Glass” in faded, sky-blue letters and a boarded-up bar called Sip Some Daiquiris. I stop at a red light next to This & That Pawn Shop, across from a café called The Cafe, which does appear to be an accurate moniker. It’s the only one in town. I knew Kentwood would be small—the cottage industry of Britney documentaries all describe it as a sleepy town, and a denizen of a Britney message board I’ve browsed periodically for years returned from their own trip here only to post that the area had a “southern gothic vibe” and note, appalled, that “there is NO WALMART, MCDONALDS, or HOSPITALS.” A visiting reporter once observed that Britney was forced to “travel an hour to shop at her nearest Abercrombie and Fitch.” I pull into a spot at the Sonic for sustenance and Diet Coke. Britney was repeatedly followed here and photographed and the resulting images posted to gossip sites. I remember scrolling the zoomed-in shots of Britney and her sister fingering fries, avoiding the camera’s eye. Britney had one hand on the wheel, the other headed for her mouth. Thanksgiving 2010.

Copyright

© The Paris Review