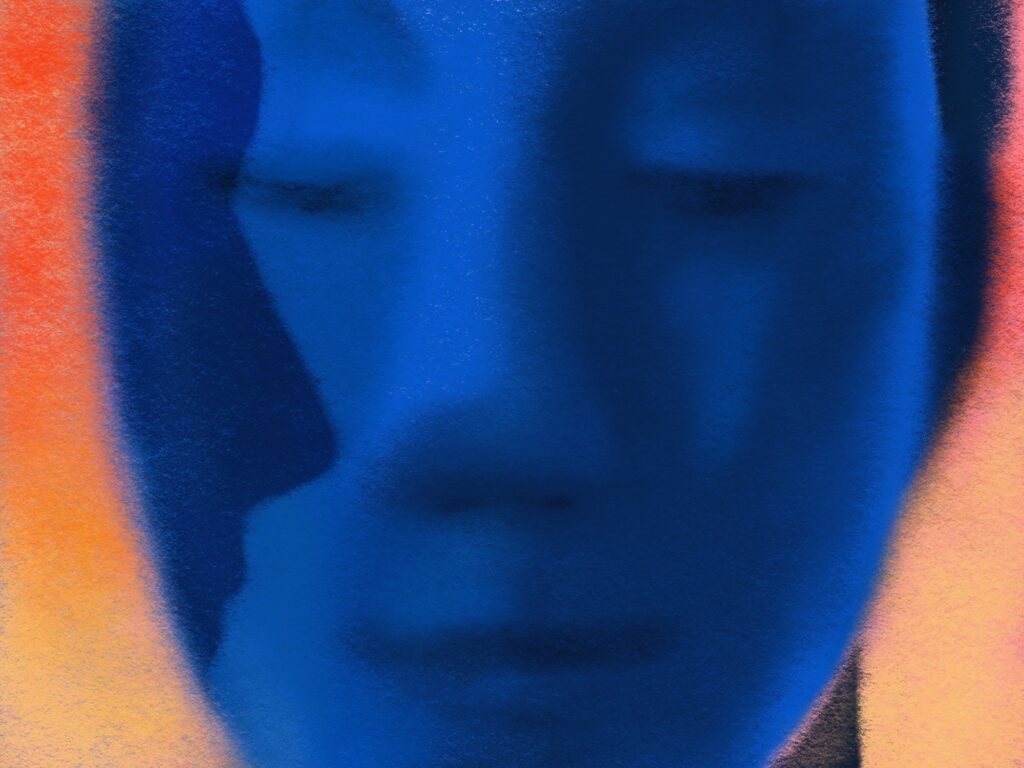

Photograph by Jules Slutsky.

The other night, the performance artist Kembra Pfahler told me some top-drawer East Village Elizabeth Taylor lore: the dame crossed paths with the about-town character Dee Finley outside a needle exchange one afternoon and later paid for Finley to get an entire new set of teeth. A quick Google search when I got home revealed that the story, as reported by Michael Musto for the Village Voice, was not apocryphal: Finley recalls Taylor arriving by limo at the Lower East Side Harm Reduction Center, circa 1997—“She had just had brain surgery. Her hair was short and blonde. Liz at her dykiest. YUM!” Taylor, who funded a lot of community work related to the AIDS crisis and had donated to the needle exchange, was apparently out and about that Thursday taking a tour to see what her dollars were doing, and also giving away bottles of her best-selling perfume White Diamonds; though Sophia Loren did it first, Taylor’s powdery Diamonds was what really made celebrity fragrances a thing. (Finley says he promptly flipped his freebie for a couple bags of junk.)

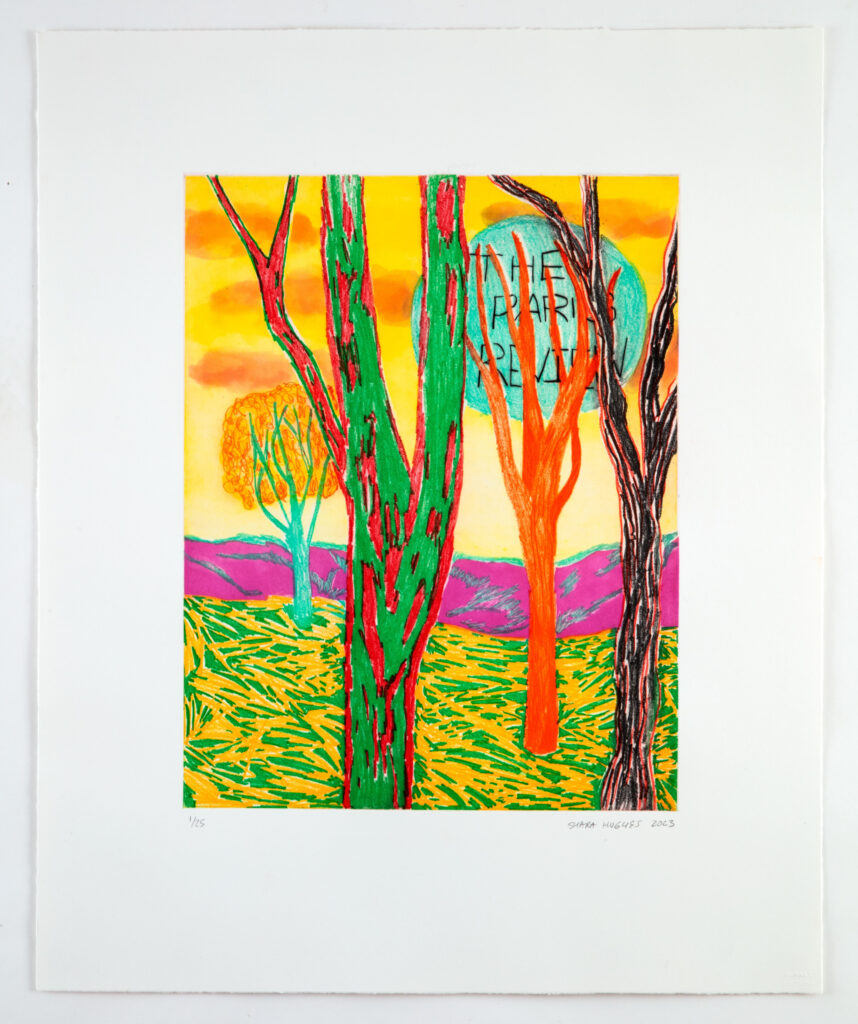

The poet and perfumer Marissa Zappas owns a pair of size thirty-eight brown leather kitten heels that once belonged to Taylor, who died in 2011. When I asked her if they smelled, she said, “Not really, vaguely of green peppers at first.” For Zappas, who’s carved out a niche for herself as an independent perfumer designing fragrances for book rollouts and art installations, as well as olfactory homages to historic figures like an eighteenth-century pirate, Taylor has been a lifelong obsession. She even used photos of her idol as visual aids to help her memorize smells when she was training to become a perfumer. Now, after establishing herself through collaborations with pros and internet-famous astrologers, Zappas has returned to Taylor as the inspiration for her latest scent, Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! Typical for Zappas, whose fragrances are more grown and nuanced than her millennial girlie #PerfumeTok fans might let on, Maggie starts off unassuming, with a warm floral musk as paradigmatically perfume-y as Grandma’s after-bath splash (it smells a bit like Jean Nate, to be specific—a summery drugstore staple since 1935). But then it develops into something more feral, a little loamy: like the inside of an empty can of Coke on a hot summer day, or freshly baked bread with a hint of wet limestone, maybe even an overripe peach traced with rot. As I lay around with my laptop in bed in the afternoon, the fragrance mixes with my sweat, its champagne and violets becoming nutty with a note as sharp as paint thinner.

The first ingredient in Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! is anisic aldehyde, a synthetic scent engineered to resemble anise seed. In its chemical structure, anisic aldehyde is somewhere between a compound that smells like vanilla and one approaching the scent of licorice. As Luca Turin explains in The Secret of Scent, modern perfumery was born in labs about a century ago, when synthetics produced to smell like lemons or roses began to replace natural extracts in fragrances. But aldehydes aren’t just one-to-one approximations of organic smells: “To understand what aldehydes do to perfumes, imagine painting a watercolor on Scotchlite, the stuff cyclists wear to be seen in car headlights,” Turin says. “Floral colors turn strikingly transparent on this strange background, at one opaque and luminous.” Aldehydes are incandescent, like Elizabeth Taylor, a delicate flower animated by something stranger, more wild.

“Complexity is hard to define and easy to recognize,” Turin writes of perfumes. Taylor’s performance in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof is instantly recognizable as that: frustrated and smoldering, yet defiantly vulnerable. The new perfume takes its name from one of her lines— “Maggie the cat is alive! I’m alive!”—spoken while pushing her avoidant husband (played by Paul Newman) to forget his recently deceased best friend and fuck her, God dammit. Maggie is desperate for his touch, Taylor convinces us with her leer, at least as much as she wants a baby to lock down his inheritance. One of the reasons we like the woman is that she’s candid about her maneuvers. She doesn’t feign any kind of moral high ground. And while she’s hardened in her determination, she’s soft enough, through Taylor’s piercing portrayal, not to hide how her husband’s neglect stings. A woman self-possessed but not uncorrupted, surrounded by all the fetid decay of a Mississippi plantation during a heat wave, willing to flirt a bit with her father-in-law, she’s a perfect Southern Gothic figure to be interpreted through perfume. Taylor playing her only makes it more fitting: Maggie the Cat Is Alive, I’m Alive! captures the stewing desire of a sex symbol unsexed.