A few years ago, I read a lecture by Chinua Achebe given in 1975, later published as an essay entitled “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” While I greatly respect Achebe’s novels, his essays have often left me wanting. His voice reminded me of my grandfather’s, the intonations of a proud Nigerian man, rightly aggrieved at the dysfunctional state of his country, his continent, and its indefatigable life in the face of rampant, extractive exploitation by imperial powers. I feel that Achebe’s frustration can leave blind spots in his arguments, and the lecture in question—an outright denouncement of Conrad’s famed novel and its canonized status as “permanent literature”—was, I thought, an example of this. Achebe considered Conrad’s novel explicitly racist in its themes, in its depictions of the “natives,” and in the gaze of Marlow, Conrad’s primary protagonist, who Achebe believed wasn’t much removed from Conrad’s disposition.

Achebe questions the meaning of writing to our society, or the meaning of any art for that matter, when it can be so explicitly racist and go mostly unremarked upon by fans and critics alike, regardless of how beautiful the turns of phrase or evocative the depictions of the lush, sweltering alien landscape. I have a complex relationship with Conrad’s novel and agree with some of what Achebe put forth, but his argument felt incomplete. Achebe’s disgust is understandable, but I think one can see Conrad was also getting at a lack of vocabulary for this rich, intricate world, of atmospheres and new sensory and metaphysical experiences, at times in his prose defaulting to beautifully phrased but reductive tropes, which are still embedded in the unconscious of Western society today. As Achebe railed at Conrad’s reduction of complex cultures, knowledge systems, and languages, down to a dark, flat backdrop for Marlow’s descent into the pit of despair, and lamented Conrad’s objectification of West African bodies, I became hooked on an important and maybe even existential question—who was Achebe’s lamentation aimed at? Who was the primary audience for his words, written in English? And was there a moral authority to hear his appeal, and if so, what then?

I envision this moral authority: a shining round table, a collective ethereal body. I can picture where this body receives education, and what information and legacy bestow upon this body to uphold such cosmic authority. I peer at this body’s ancestral responsibility and how intricately woven its cultural history is with morality, technology, and progress—through religion, reason, language, war, and subsequent laws. I wonder, wouldn’t this same moral authority Achebe speaks to be the same that has canonized Conrad’s novel, lauding it as one Western literature’s great works?

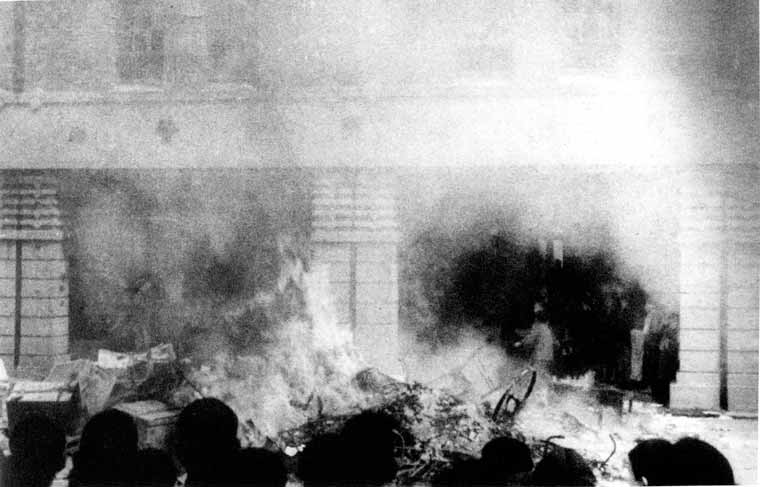

Roughly around the time of Conrad’s birth, Anglican and Baptist missionaries from Britain began spreading the Christian word across Nigeria alongside armed colonial powers, and systemically implemented a proposed order and moral structure, offering bondage under the benevolent cloak of Christianity. They found innovative ways to suppress and diminish ancient local knowledge systems whilst leveraging the locals’ deeply inherent spiritual devotion. Tribal factions with differing religious and philosophical dispositions were difficult to control without the concerted imposition of particular moral principles through Christianity. Coordinating labor and governing over resource-rich lands was made easier by exploiting the tenets of local knowledge and sowing discord between tribes. Christianity has been significant to psychological governance, by imposing a moral condition and constraining culture, dissenting thought, or ways of seeing and being alien to the new “explorers” of this productive continent of vast cultural and environmental diversity.