I like to think of literature as a second language—especially the second language of the monolingual. I’m thinking, naturally, about those of us who never systematically studied a foreign language, but who had access, thanks to translation—a miracle we take for granted all too easily—to distant cultures that at times came to seem close to us, or even like they belonged to us. We didn’t read Marguerite Duras or Yasunari Kawabata because we were interested in the French or the Japanese language per se, but because we wanted to learn—to continue learning that foreign language called literature, as broadly international as it is profoundly local. Because this foreign language functions, of course, inside of our own language; in other words, our language comes to seem, thanks to literature, foreign, without ever ceasing to be ours.

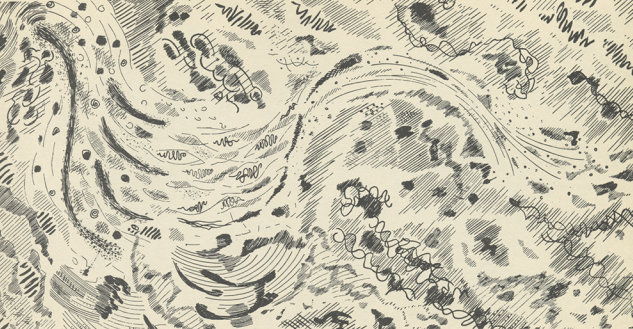

It’s within that blend of strangeness and familiarity that I want to recall my first encounter with the literature of Alejo Carpentier, which occurred, as I’m sure it did for so many Spanish speakers of my generation and after, inside a classroom. “In this story, everything happens backward,” said a teacher whose name I don’t want to remember, before launching into a reading of “Viaje a la semilla” (“Journey to the seed”), Carpentier’s most famous short story, which we would later find in almost every anthology of Latin American stories, but which at the time, when we were thirteen or fourteen years old, we had never read. The teacher’s solemn, perhaps exaggerated reading allowed us, however, to feel or to sense the beauty of prose that was strange and different. It was our language, but converted into an unknown music that could nonetheless, like all music, especially good music, be danced to. Many of us thought it was a dazzling story, surprising and crazy, but I don’t know if any of us would have been able to explain why. Because of the odd delicacy of some of the sentences, perhaps. Maybe this one: “For the first time, the rooms slept without window-blinds, open onto a landscape of ruins.” Or this one: “The chandeliers of the great drawing room now sparkled very brightly.”

Although our teacher had already told us that everything in the story happened backward, from the future to the past, back toward the seed, knowing the trick did not cancel out the magic. The magic did come to an end, though, when the teacher ordered us to list all the words we didn’t know and look them up—each of our backpacks always contained a small dictionary, which, we soon found, was not big enough to contain Carpentier’s splendid, abundant lexicon.

Was that how people in Cuba spoke? Or was it, rather, the writer’s language? Or were we the ones who, quite simply, were ignorant of our own language? But was that our language? We discussed something like this, dictionaries in hand, while the teacher—I don’t know why I remember this—plugged some numbers into a calculator laboriously, perhaps struggling with his farsightedness.