Courtesy of Mary Gaitskill.

Before my father died in 2001, I knew that I loved him but only dimly. I didn’t really feel it, and to the extent that I did, I experienced it as painful. When he was dying I almost didn’t go to him. When I was trying to decide whether to go, someone asked me, “Do you want to see him?” And I said, “That’s hard to say. Because when you’re with him you don’t see him. He doesn’t show himself. He shows a grid of traits but not himself.” Still, I decided to go. The death was prolonged. It was painful. Because of the pain, the “grid” that I referred to—my father’s style of presentation—could not be maintained. A few days after I arrived, my father lost the ability to speak more than a few words at a time. But his eyes and his face spoke profoundly. I saw him and I felt him, and I loved him more than I thought possible. I was stunned by both the strength of my feeling and my previous obliviousness to it, and by my realization that, if I had not come to see him, I would never have known how real my feeling was or how beautiful it was to say it and to hear it said.

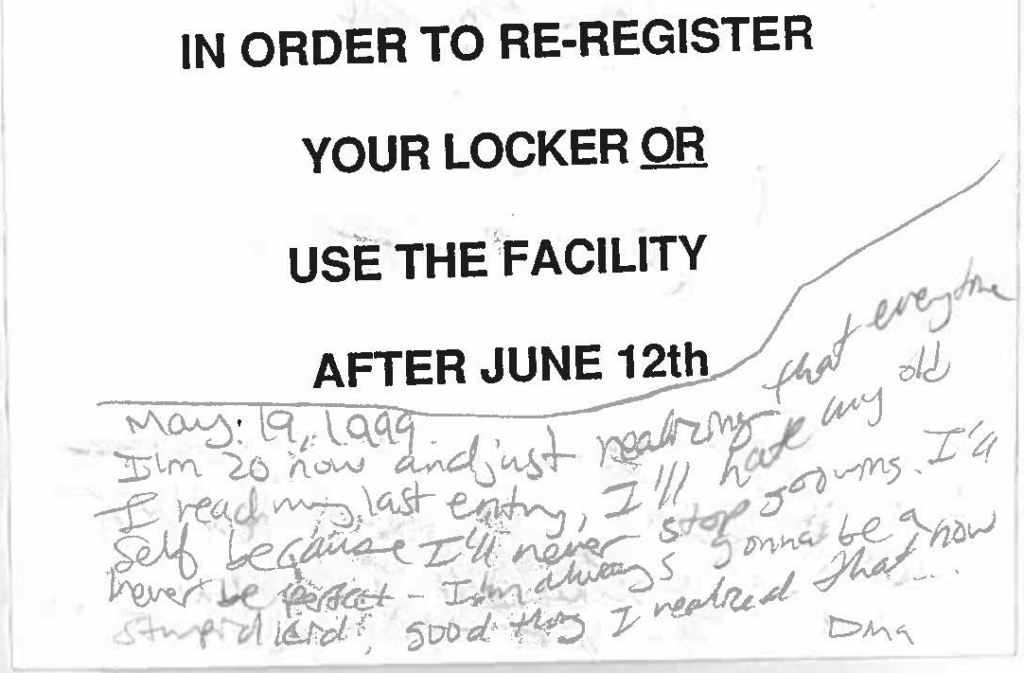

I recall that, at the time, I had a mental picture of this experience that looked like one of those practical joke containers disguised as a can of nuts or something; you open the lid and a coiled cloth-covered spring leaps out at you—it felt that startling. This image was followed by another mental picture, an image of human beings as containers that hold layers and layers of thought, feeling, and experience so densely packed (“the body remembers everything”) that the (human) container can be aware of only a few layers at a time, usually the first few at the top, until and unless an unexpectedly powerful event makes something deep suddenly pop out, throwing some elements of the “self” into high relief and disordering others, hinting at a different, truer order that was there all along.

My father wanted to stay at home and so he did; he suffered in his own bed almost up until the end. There was only one hospice worker coming in a couple times a day to give him care plus morphine, which wasn’t strong enough and to which he became quickly accustomed. My sisters and I didn’t realize until quite late that we needed to keep upping the dose; he couldn’t speak by then, though he grimaced in rage and pain.

One of his few visitors during this horrible time was a minister named Amory Adamsen. He was a minister with some kind of half-assed training as a counselor. Before my parents separated, my mother requested that they try counseling. I think she requested it because she’d been going to AA meetings for years and had the lingo down cold; she probably thought she’d be seen as this reasonable person while he’d be seen as a mad, pawing bear, and she’d have official permission to dump him. But my father would agree only if it was a Christian counselor, even though he wasn’t a Christian, and so Mother came up with this Adamsen person. All I knew about him was that (according to Mother) he considered my father the “least introspective person” he’d ever met and that he’d also quite avidly read my novel Two Girls, Fat and Thin, which is about, among other things, a girl being raped by her daddy. He even came to a reading of that book I somewhat cluelessly performed in Lexington (on Mother’s Day!); he gave me his full pious and slitty-eyed attention while my poor father wandered the aisles. Now here he was at the house with my father upstairs dying. Apparently, he and my dad had kept up contact long after my parents’ separation, going to basketball games over the years. Although the prick hadn’t returned my father’s last call about a game, here he was, smiling at everyone, hugging, dispensing comfort, looking around. He told my father he was sorry about missing the game, which I do not think my father gave a fuck about at that point. He told him he’d sure enjoyed getting to know him. Then he mingled with my uncle and his wife, with me and my sisters. He kept singling me out with his eyes and finally asked if he could talk with me privately, that he had something to ask. So we went upstairs, shut the door, and he revealed that what he wanted to know was: Did my father really sexually abuse me? He said that he knew just how rude and inappropriate it was to ask, and he added that if I was offended, he was so sorry, he’d just drop it. I said that whether I was offended depended on why he was asking. If it was just curiosity, yes, I was offended. But if it was a moral concern and had something to do with what kind of prayer he wanted to say, that was different. He allowed that he was curious and that he knew it wasn’t his business and he was sorry. I maybe should’ve hit him and walked out of the room, but just so he would know, I said my father never did anything like that, what I wrote was fiction. Amory said he knew it, he knew my father was very moral, he was no sex pervert. I said, “Well, actually he was, but only a little, no more than average, really.” This confused the moron, but he got over that and said that even though he knew my dad was innocent, there was always this tiny question in his mind, and he was glad to finally put it to rest. He went on to declare, however, that even if I had said yes, my father raped me, it wouldn’t have made a bit of difference, that he liked my dad a lot and would’ve made no judgment. We talked about how awful molestation is and how much of it there seems to be. He said my dad had worried about me. For example, he had always wondered why I didn’t get married and was concerned that I might be a lesbian. I told him that I was in fact getting married. He seemed disappointed. He went into my dad’s room to pray at him and I went downstairs to tell my sister Jane about this idiotic conversation. My sister said that although she had been planning to ask Amory to speak at the funeral, after hearing this, no way. We both decided not to tell our mother, who was easily upset about the subject of my writing just generally. Naturally Amory Adamsen wound up speaking at the funeral. I didn’t stay for that event so at least I didn’t have to listen to it.