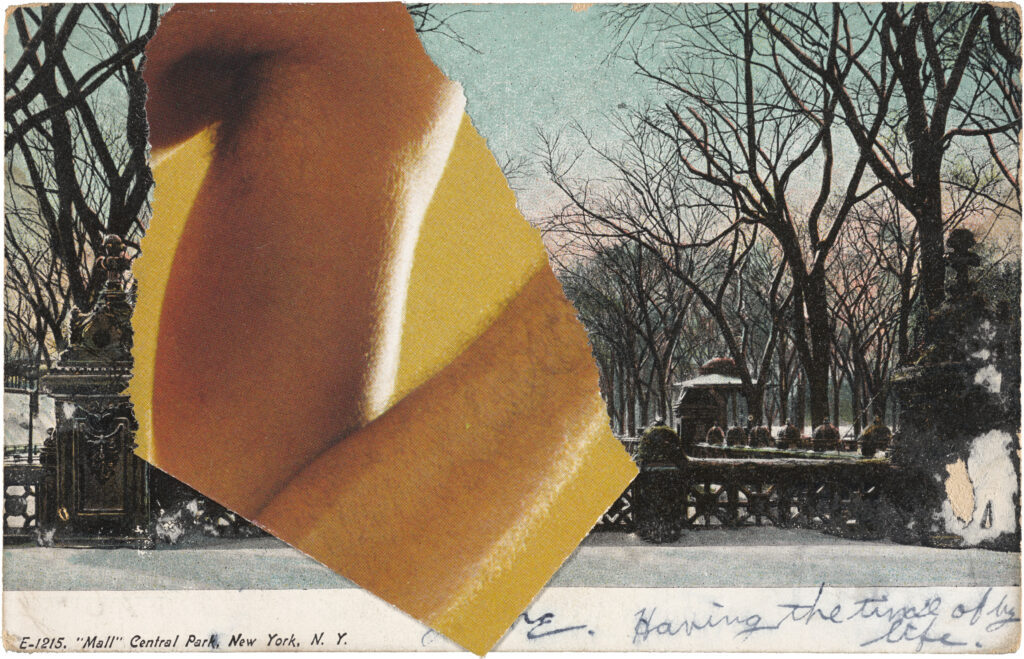

Penumbra (2022), by Hannah Black and Juliana Huxtable. Press image courtesy of the artists and Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève.

I frequently feel saddened and angry that animals—whom I love, sometimes feed, and never eat—mostly ignore or even run away from me. For this reason, I enjoyed Hannah Black and Juliana Huxtable’s animated film Penumbra, which stages a court case against a nonhuman defendant—“representing all animals or the animal as such”—that is on trial for crimes against human beings in contempt of human reason. The judge is an animal, the members of the jury are animals, too; from the beginning, power and numbers are on their side. There are two humans, but they’re dressed as creatures: “Juliana Huxtable,” the defense, is costumed in furry-esque bunny ears, which mirror the headdress worn by the prosecution, and “Hannah Black, genus homo, species sapiens” recalls the animal-headed Egyptian god Ra (in Derrida’s reading of Plato, the father of reason or logos). The CGI places human and nonhuman characters on a fair—and very low poly count—playing field of unreality. And so the debate begins.

But it’s really a monologue: Huxtable speaks only rarely; her nonhuman “kin,” never. Animals, here, are outside the realm of representation, in both the legal and the semiotic senses. It’s a canny dramatization of the absurd, unhappy impasse posed by the discourse of anthropocentrism, which, in its attempt to “decenter” people in favor of a more inclusive worldview, must also mute the capacity that enables discourse (and community, identity, thought) itself. This capacity is both subject and object, content and container, of Black’s breathless address. “Through the use of language,” she begins, “I will show you, and you will understand, and through doing so you will have to admit that you do not fundamentally sympathize with the principle of the animal, you respond to abstract concepts, you know how to come when your name is called.”

Yet the dazzling avalanche of words that follows is less an airtight argument and more a poem with the rhetorical texture of a rant. Penumbra isn’t just an intervention in theory masquerading as video art; it brilliantly reveals, aesthetically, what analysis cannot: the illogic, the nonhuman, within language and hence within us. Black’s rapid-fire circumlocutions and cascading repetitions are actually impossible to follow; instead, they are reduced to an ebb and flow of breath and rhythm that wash, anxiously, over us. The animals, of course, refuse to respond to her questions, her attempts at taxonomy: “Do you deny that you practice cannibalism?” Legally, the word penumbra refers to constitutional rights inferred using interpolative reasoning; in science, it connotes the gray area between a light and a shadow. This trial is an arbitration of gradients via an indictment of law: a tragedy of reason that makes a mockery not just of justice, but at all of our attempts at living in harmony.

It’s a sign of our species’ self-hatred that most people in Sunday’s audience at Metrograph—where the film screened along with two others from the 2021 Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement—seemed to interpret Penumbra as a celebration of the inevitable triumph of the inhuman. Maybe they’re right. And no one wants to sympathize with the prosecution! But I felt so bad for us, the tiny minority in a universe that, though sensate, is senseless. As Black’s character says, “We have tried to hold on to the collective being, but the animal refuses to speak to us. All that we know about brutality we learned from animals. We learned how to treat each other as food, we learned how to die indifferently.” Aprés nous, le dèluge, I thought, despondently, leaving the theater.

Copyright

© The Paris Review