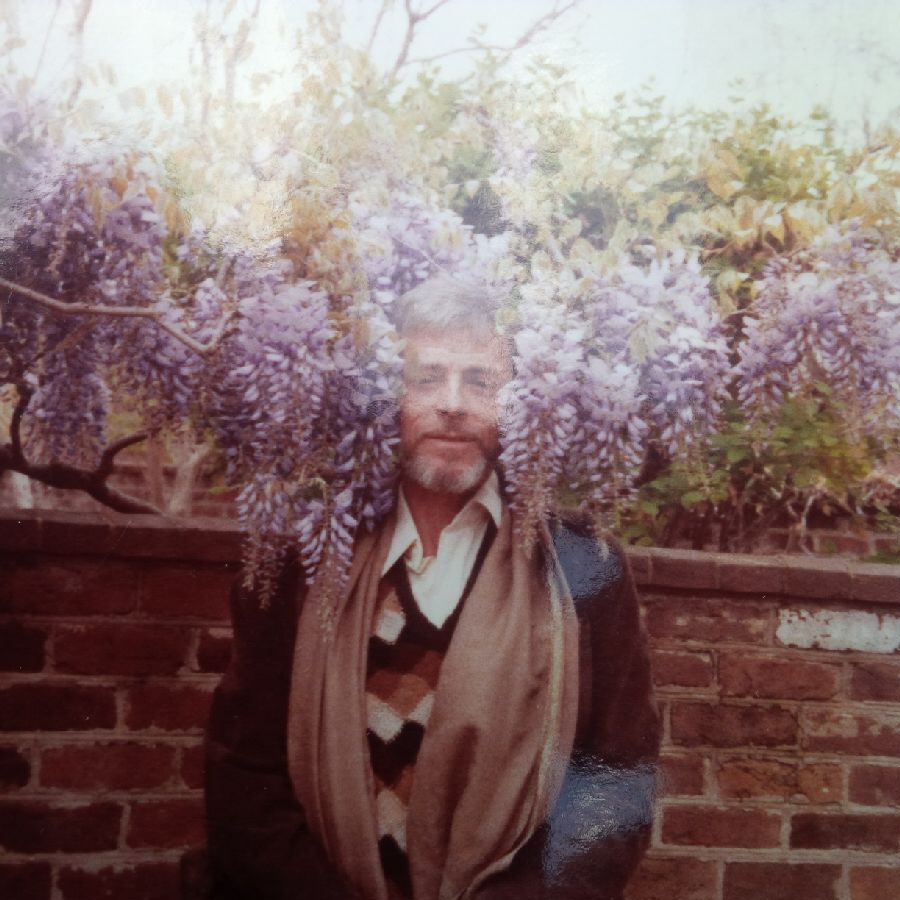

Photograph by Maya Binyam.

July 24, 2022

I live in LA, but I’ve just flown in from New York after a month away, so I wake up early, too early, at 4 A.M., and read a book called Healing Back Pain. The author, John Sarno, is a doctor who argues that most back pain is psychological—the result of tension, which arises from repressed emotion. He makes his perspective sound like the most obvious thing in the world, and makes the common explanations, like sitting too much, sound completely idiotic. Most people have been taught to think of chronic back pain as arising out of an inciting incident and to think of the spine, especially the lower spine, as very fragile—even though, he explains, bodies are resilient and spines exceptionally strong. I want to believe him, because if I do believe him I’ll never feel back pain again, or if I do, I’ll have my delicate psychology to blame, as opposed to an innocent object like my chair. Sarno has a cult following; I google him, careful to read only the testimonials about how the book has changed people’s lives. Then I fall back to sleep.

I wake up again, at 7 A.M., make tea, and open all the mail I got while I was away—health insurance bill; traffic ticket; copies of Dogs of Summer by Andrea Abreu and A Woman’s Battles and Transformations by Édouard Louis; the new Paris Review; and a couple of issues of the London Review of Books. I read a review of Either/Or by Elif Batuman, a book that made me very angry. I was nevertheless gripped by it, as I was by The Idiot, probably because both present a problem that I’m still working out and which I’ve encountered in many novels that I might otherwise be inclined to say I enjoyed. I always feel betrayed by characters with whom I begin to identify—not necessarily because my life or psychology is like theirs, but because I can understand the contours of their journeys and want to follow them through—who then, in brief and passing moments, reveal the limits of their worldview, ushering in black people or poor people or people who speak in halting English as props to signal the boundaries of their otherwise astounding capacities for empathy. I have no interest in reading about characters who are likeable, or about characters who are inclined to like people like me, but I have a hard time not seeing it as a failure of a book’s attention to detail when people are turned into metonyms for cultures and ideologies with which the novel is unwilling to engage; it feels almost like the opposite of virtue signaling: a brief and passing confession that the protagonist is (of course!) burdened by the ugliness of her social class. Almost every review I’ve read of Either/Or mentions Selin’s naive and enthusiastic embrace of great works of literature, which she reads as instruction manuals for how to construct a life; none mentions her stated difficulty in appreciating hip-hop, which she summarizes as an altogether alienating genre of music defined by a man “saying ‘Uh, uh’ in the background.” (“Killing Me Softly” by the Fugees proves, for Selin, to be the exception to the rule, because “the man, despite several false alarms, never did start rapping, and instead a girl sang an old song with beautiful harmonies.”) But I don’t know—obviously Either/Or wasn’t going to be entirely about Selin’s problematic relationship to hip-hop. That would be a horrible book.

Edits on my novel are due next week, so I’ve vowed to do nothing and see no one until I finish. I spend the rest of the morning line editing, and then do a YouTube exercise video that involves flailing my limbs around as if I were lifting and then dropping a series of heavy objects. The couple in the video tries to be motivational and in the process takes a very derogatory stance on exercise, emphasizing how difficult it is and how happy we’ll all be once it’s finally over. Every time they demonstrate something especially excruciating, they repeat that “there are thousands, maybe millions” of other people suffering alongside me, which seems like a gross overestimation of their audience.