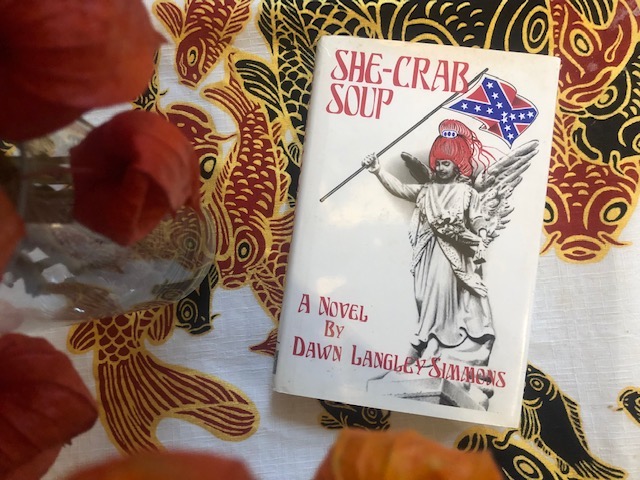

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” Virginia Woolf once asked a little boy named Dinky, in the gardens of Sissinghurst Castle, the home of Woolf’s loverVita Sackville-West. “A writer,” Dinky replied. As in a fairy tale, the child’s wish came to pass: Dinky, who was born Gordon Langley Hall, the son of Sackville-West’s chauffeur, went on to become the author of twenty books, including She-Crab Soup (1993), a high-camp Southern Gothic novel about the romantic adventures of a wealthy Southern belle—a story as remarkable as the author’s own life. By then, the former Dinky had undergone a series of dramatic self-reinventions, having transformed herself from the illegitimate son of working-class Brits to a cultured expat author living in Charleston, South Carolina. And in 1968, at the age of forty-six, she transitioned, rechristening herself Dawn. She was, as Simmons—who eventually took her husband’s surname—wrote in her memoir, “a real-life Orlando.”

Simmons’s life was packed with escapades that would not be out of place in that novel, involving a host of figures whose stories she weaves into her own. Her account of her childhood that she gives in her autobiography, Dawn: A Charleston Legend (1995), features a Spanish great-grandmother who spent the first seventeen years of her life in an Andalusian convent, in hiding from her father, a wrath-filled duke; a cousin who died in the 1917 Russian Revolution; and an uncle who invented a fizzy drink that was supposed to bring him fame and fortune but who was paralyzed when he accidently shot himself in the spine while rabbit hunting. At the age of sixteen, Simmons set sail for Canada, to spend a year as a teacher on an Ojibwa First Nation reserve on Lake Nipigon. Two years later, she published her first book, Me Papoose Sitter (1955), a comic account of the experience. By this point, she’d moved to New York, where she met the famed painter and muralist Isabel Lydia Whitney, a wealthy grande dame in her seventies.

Whitney invited Simmons to live in her art-bedecked town house in Greenwich Village, where she introduced her to Princess Ileana of Romania, who “had escaped from the Nazis in World War II, bringing her crown wrapped in a nightgown,” and the author Pearl S. Buck, among others. Simmons also met the British actors Margaret Rutherford and Stringer Davis; the older, childless couple asked the youngster if they could adopt her—if not legally, then “from the heart”—and she agreed. Henceforth, they became “Mother Rutherford” and “Father Stringer,” and the ailing Whitney was able to shuffle off her mortal coil without worrying about who would look after her beloved companion. When Whitney died in 1962, she left Simmons a tidy inheritance and a mansion in Charleston—the Holy City, as it’s been nicknamed—that later became the setting of Simmons’s first and only novel.

While living in New York, Simmons began a career as a writer of celebrity biographies. Before her death, she would go on to author upwards of a dozen portraits of high-society icons, from princesses to First Ladies. This keen eye for sparkling personalities also finds a happy fictional outlet in the motley band of characters of She-Crab Soup; the memorable coterie of oddballs gives the eccentrics in John Berendt’s Savannah-set Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1994) a run for their money. The novel’s heroine is Miss Gwendolyn, a wealthy British expat and writer of gardening books. The story opens in 1969, by which point Miss Gwendolyn has been living in Charleston for ten years, ever since she inherited a mansion, along with two trusty servants—Mr. James, the butler, and Miss Frances, the cook—from her godmother, Miss Annabel Pincklea. Shortly after her arrival, Miss Gwendolyn also acquires a fiancé—Mr. Pee, the son of her next-door neighbor. The epitome of a Southern gentleman, Mr. Pee is considered a “prize catch,” although he still sleeps with his teddy bear and is tied to the apron strings of his mother, Miss Henrietta, and his elderly Black nurse, Maum Sarah, both of whom are determined that he “should go to the altar the most spotless of bridegrooms.” As time goes by, poor Miss Gwendolyn begins to doubt whether this will ever come to pass; engaged for a decade, they’re still no closer to actually setting a date.

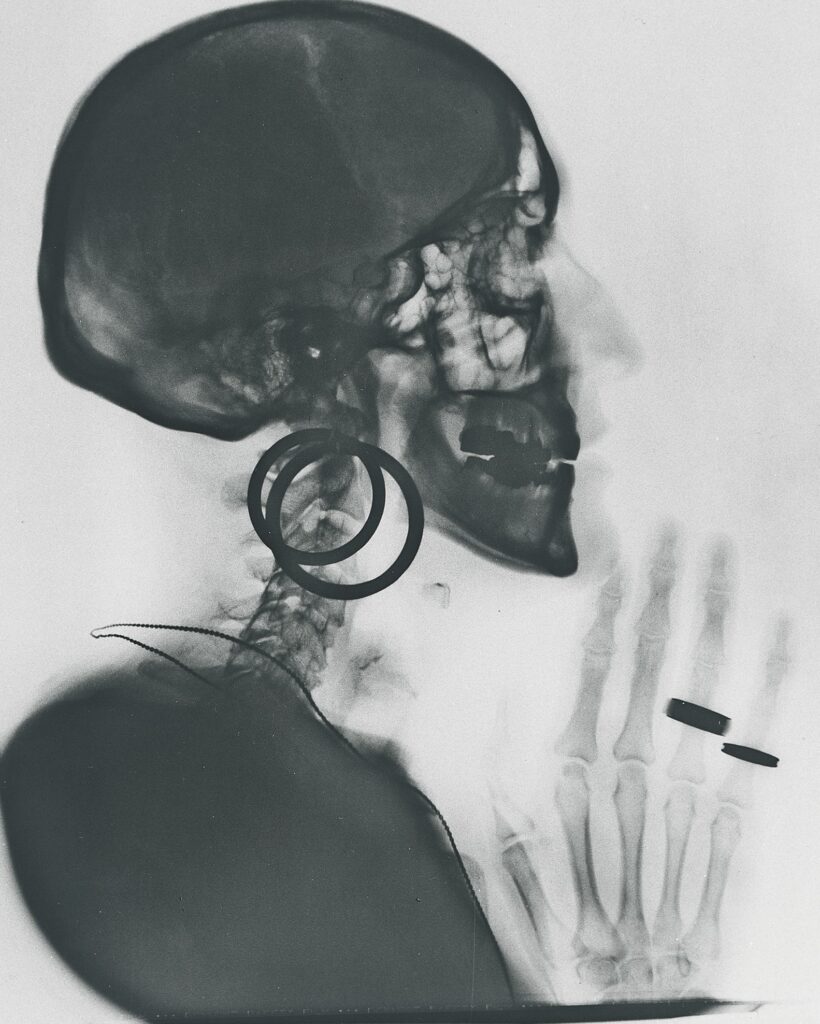

Enter Big Shot Calhoun, who left school at twelve to become a pimp, and claims to once have seen a marble angel come to life in the local cemetery. Big Shot and Miss Frances are something of an item—she’s devoted to him, though he’s decidedly less enchanted—and following one of their many misunderstandings, he turns up at the Pincklea mansion late one evening, looking to make amends. When Miss Gwendolyn answers the doorbell wearing her white crepe de chine nightgown, Big Shot thinks she’s his angel, and immediately determines to marry her, tout de suite. He returns in the middle of a raging storm to profess his undying love, dripping wet and clutching a pail of orange calla lilies and pink crepe myrtle, and the scene quickly descends into cartoonish burlesque. A furious Miss Frances chases him around the dining room with a carving knife (followed closely by Mr. James, armed with a rolling pin). Overwhelmed by the sheer force of his attention, Miss Gwendolyn accepts Big Shot’s proposal, so Miss Frances packs up her collection of Barbara Cartland novels and marches out the door hollering about retribution, only to be struck down by lightning on the front steps. (She’s slightly charred—“wisps of smoke curling up from her tattered clothes, her hair standing up in frizzles on her head, a twisted skeleton of an umbrella in her hand”—but otherwise unhurt.)