Postcards from Ellsworth

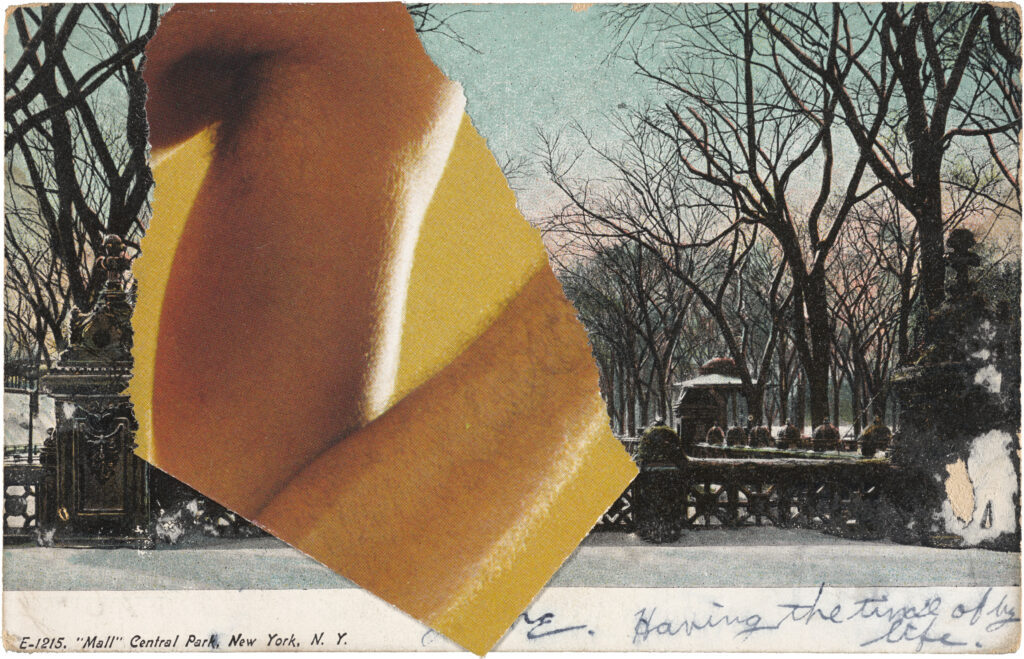

Ellsworth Kelly, Having The Time Of My Life, 1998. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

1

Several years ago, moving into an old but new-to-me apartment with bare white walls, I tacked a poster-size sheet of heavy paper above my desk. Over time, I began to randomly pin found photographs and scraps of stories and poems to this sheet—including a couple of reproductions of Ellsworth Kelly postcards, which I’d torn out of magazines. Every so often, my eyes would stray upward, and these flashes of color would slide into view. I had not thought of them again until very recently, when I heard of an exhibition curated from the four hundred postcards Kelly made and mailed at various points during his seven decades of making art.

I did not think much then about why they appealed to me. Some of the other images on my board were actual found photographs, as in ones I found on the street, including a glossy, black-and-white roadside image of a crime scene, probably photographed by highway patrol, then ripped in half. Like the collages I sometimes made on notebooks containing my first drafts, none of these pictures were meant as literal inspiration; they were just references for daydreaming, vague and strange enough that they might compel some unexpected sentence or train of thought.

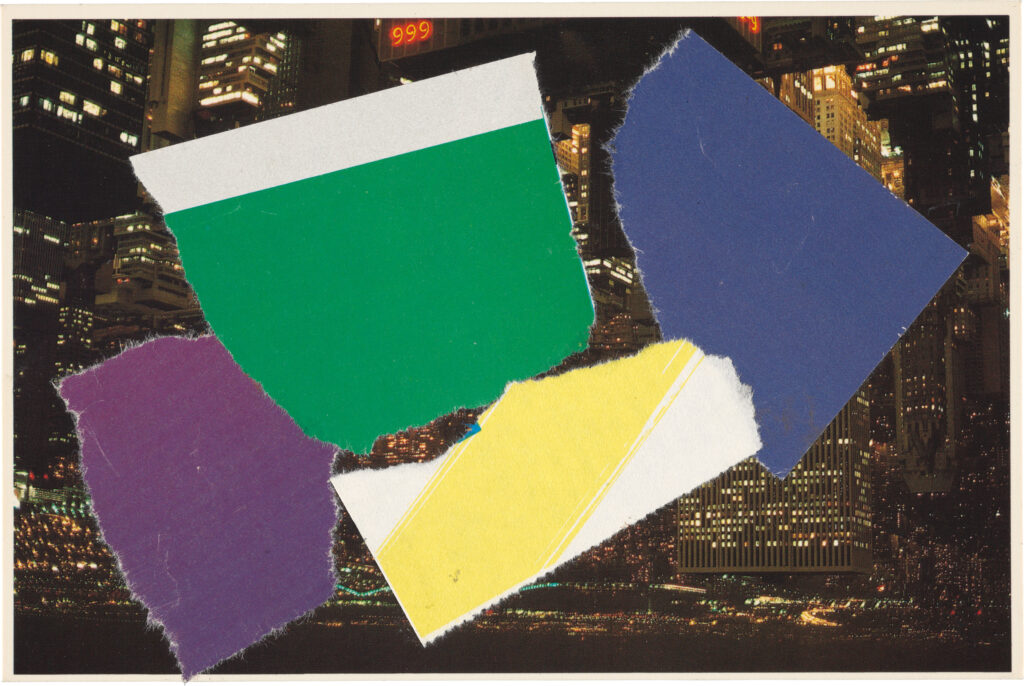

In one of the Kelly postcards I’d pinned up, four irregular squarish panels of slightly diluted shades of blue, yellow, green, and red are pasted like a scrim over a landscape of a mountain and lake. They reminded me of endless things, like Baldessari dots that simultaneously redirect the eye elsewhere and draw it back to the point of obfuscation, piquing curiosity about what it conceals. In their pure arrangement of color, the postcards were pleasingly like the faded multicolored flags that flutter over used car lots, like the surprise patterns and colors of paint that emerge on adjacent boarded-up windows when old city buildings are torn down. They were both curtains and windows, shielding what lay behind them and opening into something else.

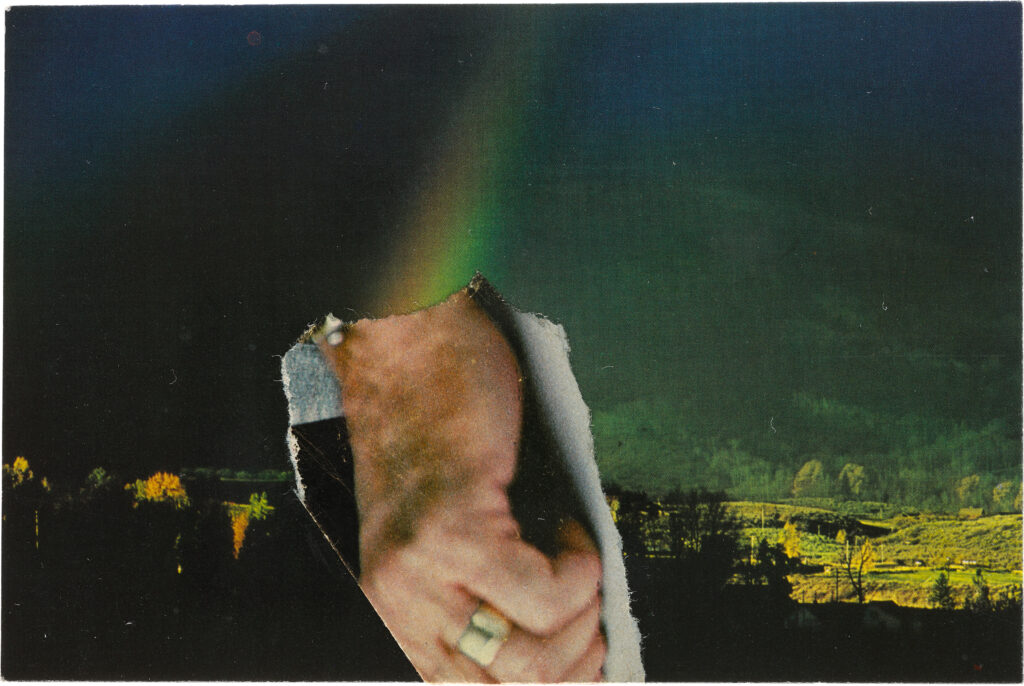

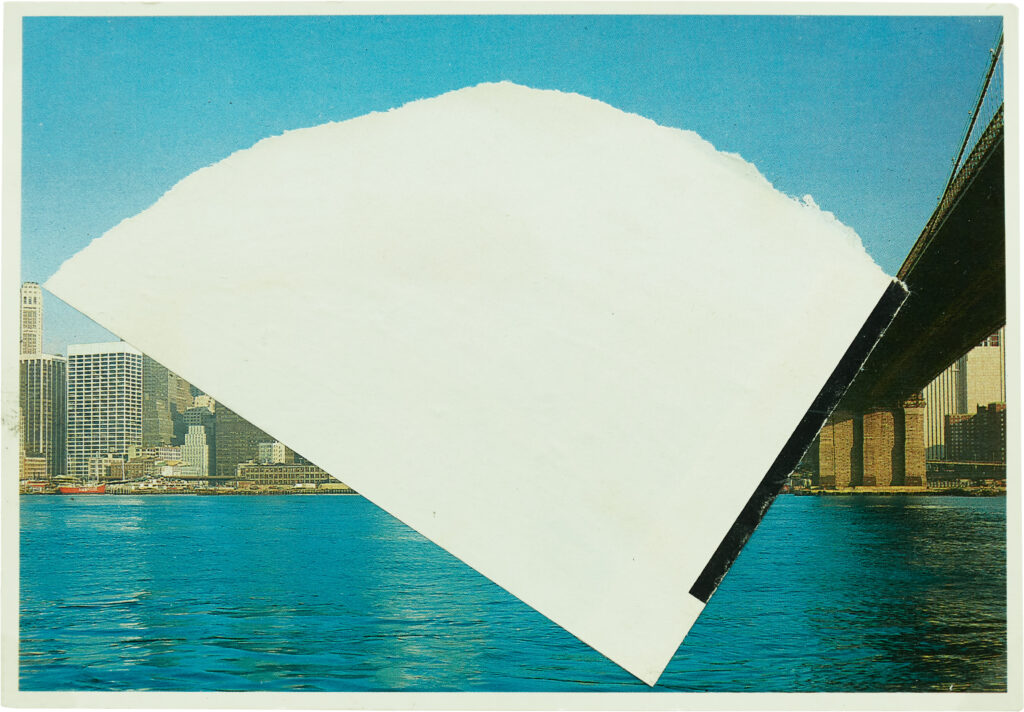

Ellsworth Kelly, Brooklyn Bridge II, 1985. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

2

The first postcard collage Ellsworth Kelly made and mailed featured a cut-out sphere of red paper pasted against a blank background, upside down; along with a scrap of blue paper torn from a pack of Gauloises cigarettes. It was 1954, in the first week of Kelly’s return to New York City. He stamped it and sent it to his friend Ralph Coburn, an artist he’d known in Boston, who was then living in France.

Kelly was thirty-one years old, back in the United States after a transformational six years in Paris, and finding his way into abstraction. In Paris, he’d met John Cage, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, and Jean Arp. In his 1990 essay “Fragmentation and Form,” Kelly noted how Kasimir Malevich’s squares blocked religious material so that “color became his content”—the abstraction of Russian icons signaling the artist’s commitment to “picturing transcendental realities.” He was exposed to Surrealist automatic drawing, Schwitters’ collages, and also the work of the Arps, whose collages were “were my first introduction to fragmented forms arranged by laws of chance.”

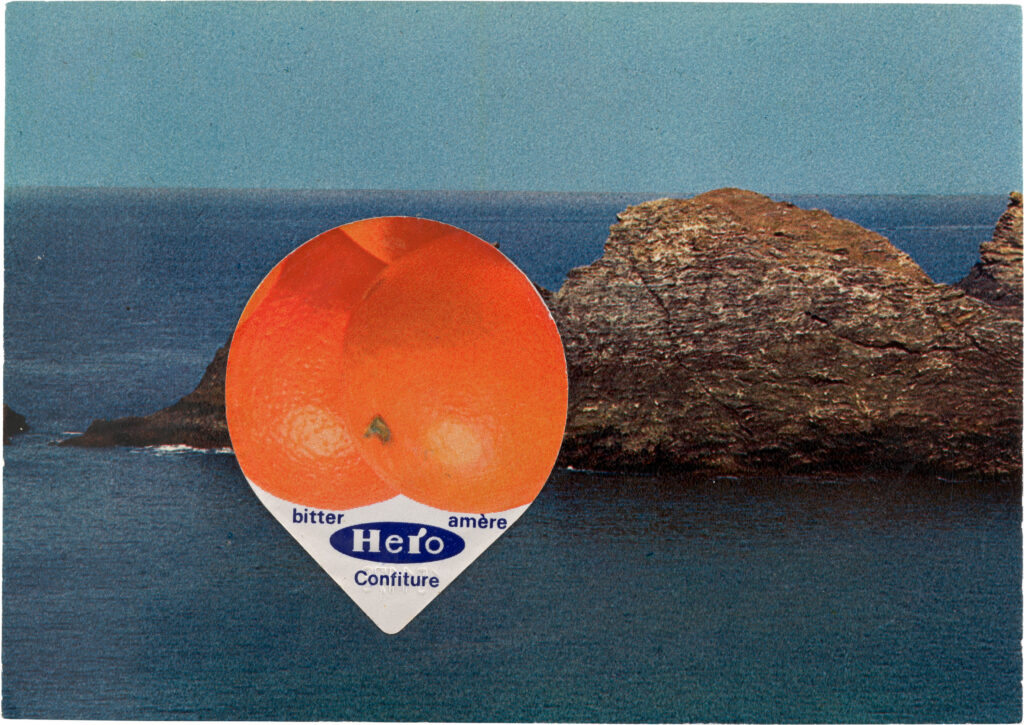

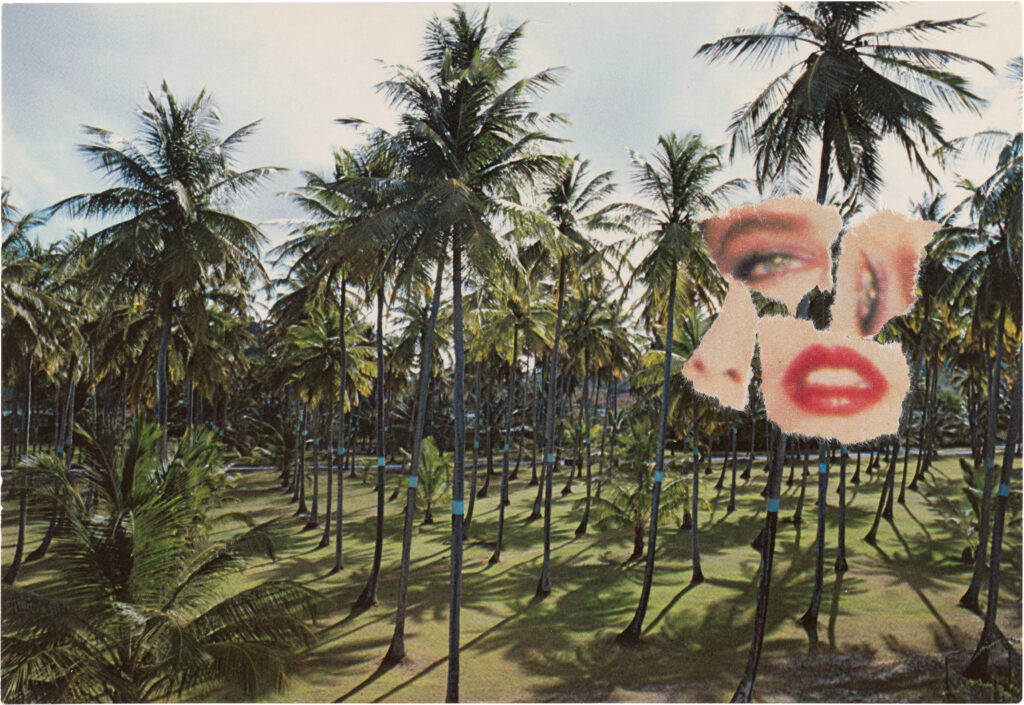

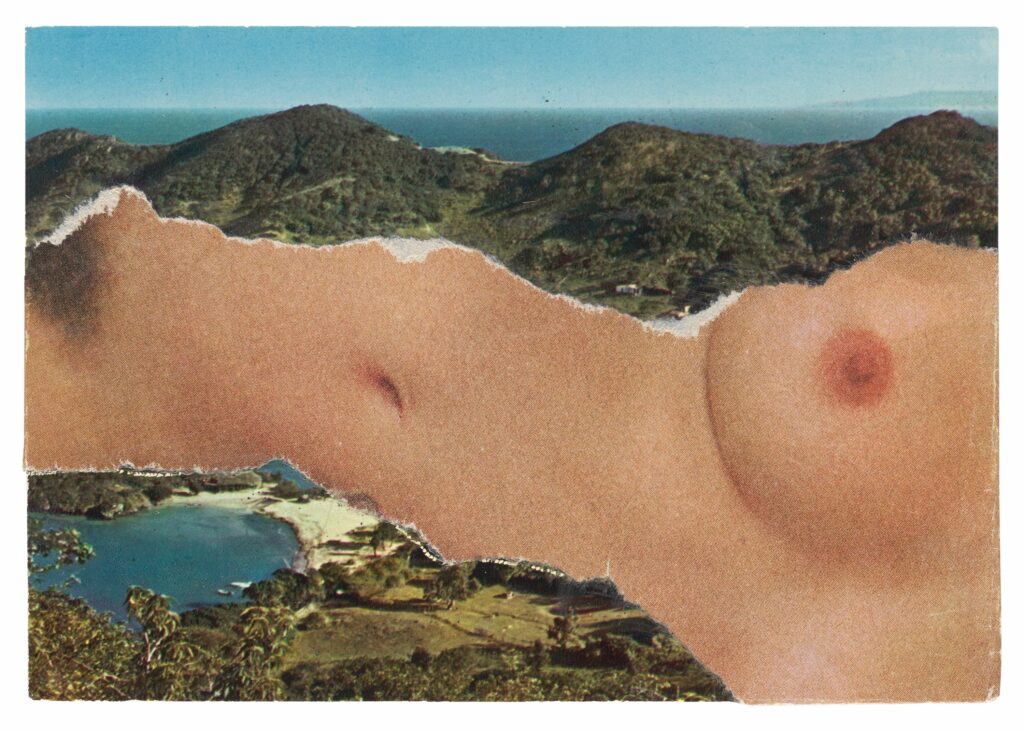

Ellsworth Kelly, Images des Antilles 2/5, 1984. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

3

During the Second World War, prior to his years in Paris, Kelly had enlisted in the army. He did this “to get away from his family, especially his mother,” Jack Shear, his longtime partner, once said. Kelly served in the Ghost Army, a tactical military unit comprised partly of artists. Kelly and his comrades created inflatable tanks and entire fake military camps—illusions and obfuscations in the landscape, designed to throw the German army off course.

On one level Kelly’s postcards can be thought of as a kind of Ghost Army correspondence. The opposite of camouflage, his cutouts insert themselves in unlikely settings, winking at the presence of the surreal. His forms and fields of color create imaginary portals in banal postcard landscapes: a cut-out paper moon floats above a generic Manhattan skyline, or drops of blood dribble on a torn white page, collaged over sand dunes. Panels of black, yellow, red, and green descend on grainy, washed-out images of fields, crashing seas, baseball stadiums.

For Kelly, postcards were a vacation from the studio. They were both outlet and outline, made quickly and intuitively: Some were places to work out ideas, and a few loose compositions would lead in more obvious ways to larger, more fully realized pieces. Others were just to escape, to play and have fun. All of Kelly’s postcards, though, were equally sketch and message—a brief transmission from wherever he was in the world and in his mind, a glimpse into his creative daydreams, and an invitation for the recipient to see as he saw.

Ellsworth Kelly, Manhattan Skyline at Night, 1985. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

4

Kelly’s abstract shapes were often pulled from the natural world. He framed and isolated snatches of reality much in the way a photographer attempts to do. “I want to catch one thing that’s a flash, a mysterious thing, the beginning of something, a primal thing,” Kelly said in 2008. But even as he acknowledged this desire to stop time, to freeze and distill the everyday, he surrendered to and celebrated the impossibility of doing so. Growing up, Kelly was a birdwatcher, perpetually looking out for fleeting, uncanny colors and markings. After his death in 2015, one of his famous quotes kept circulating: “ What I’ve tried to capture is the reality of flux, to keep art an open, incomplete situation, to get at the rapture of seeing.” His postcards contain the surprise of a well-delivered punchline: interruptions in otherwise stale depictions of beauty.

5

Can you imagine the person who tosses out an Ellsworth Kelly postcard? But some friends apparently did. He stopped sending them to those people.

Kelly also began to suspect postal workers of stealing the postcards. Presumptuous or not, perhaps he knew something from the inside. He worked at the post office himself when he returned from Paris, in Manhattan’s giant Beaux Arts main branch at Eighth Avenue and Thirty-Fourth. Long shifts of sorting mail, interrupted, occasionally, by the sight of something a little out of the ordinary, perhaps handmade, with no obvious value. What would compel a person to steal such a thing, or to get rid of it?

Despite his suspicions, he continued to make them.

6

For artists, postcards are often attractive propositions—semi-intimate and semipublic, their audience largely accidental and mostly postal. They possess inherent formal restrictions, and their own strange vernacular. Kelly’s hewed to the tradition of postcard pieces made by Miro and Duchamp, which often had often had a similar element of humor, tactile elements, and deliberate, wildly inaccurate scales. He also acknowledged the influence of Ray Johnson’s mail art. And he had antecedents, too: His postcards played with the notions of tourism and place that Zoe Leonard would later explore in her 2008 series You see I am here after all. In Leonard’s series, near-identical view card representations of Niagara Falls proliferate, the visual experience diluted by repetition.

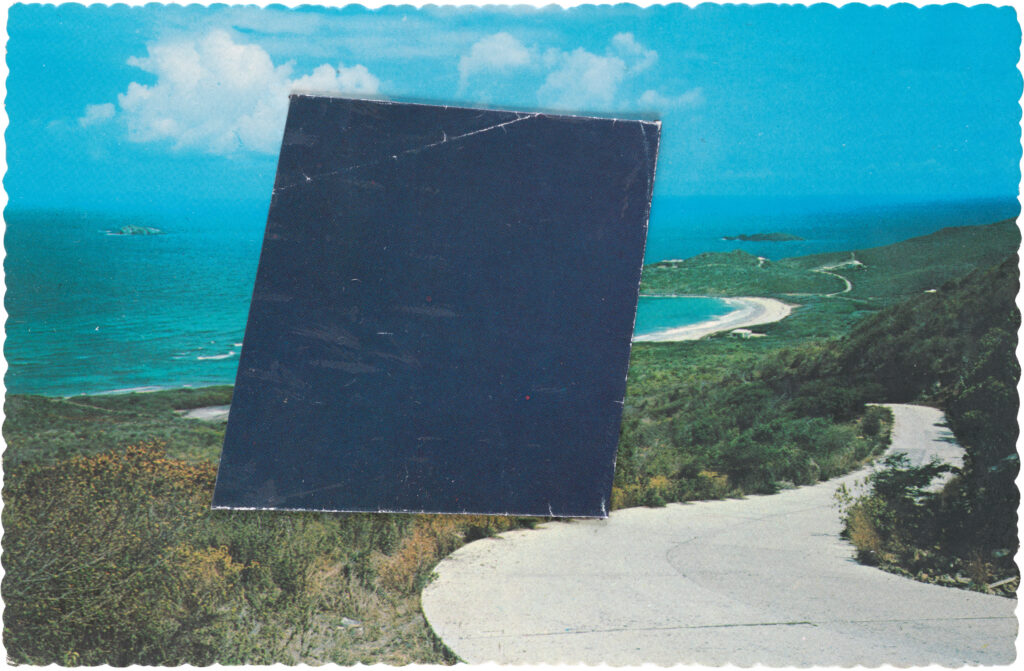

Ellsworth Kelly, Oyster Pond (Blue Form), 1977. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin.

7

There is kinship too in Stephen Shore’s photograph U.S. 97, South of Klamath Falls, Oregon, July 21, 1973 — a billboard of a painting of Mount Shasta. Its blues, whites, and yellowed greens blend in with the actual land that surrounds it. Its flatness transcends the natural landscape, competing with it. The text of the billboard has been blotted out with two rectangles of paint, blue and black. It feels close to Kelly’s own games with scale: like one of his postcards blown up and planted in the world.

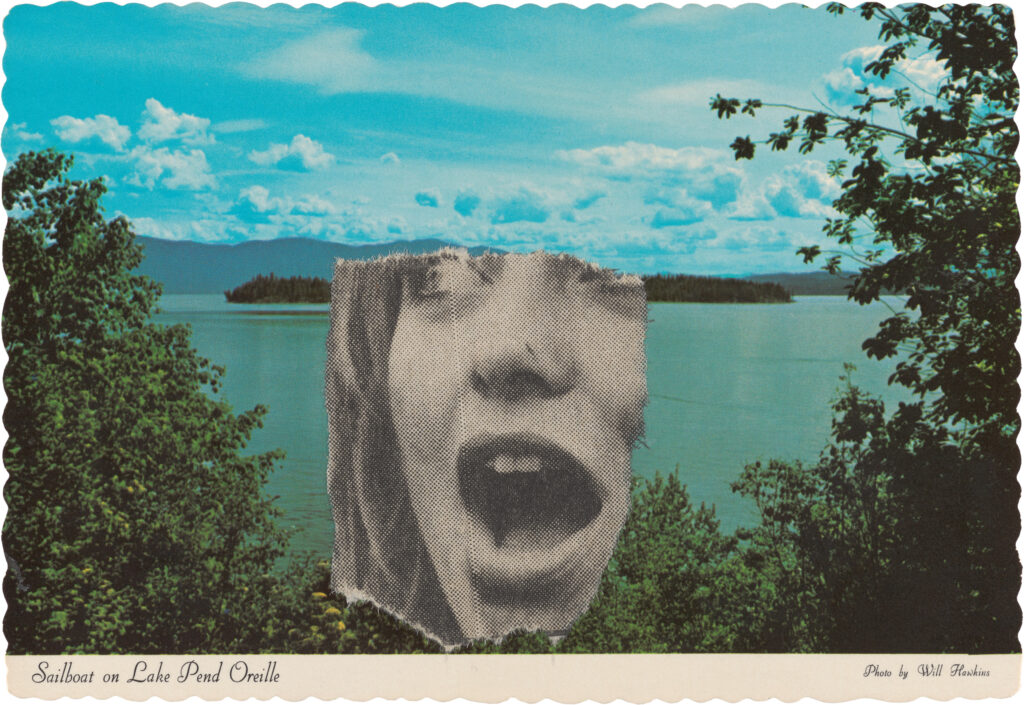

Ellsworth Kelly, Sailboat on Lake Pond Oreille, 1977. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

8

Even though they weren’t the real things, the images of the Kelly postcards I collaged on my wall still bore the curlicue border all postcards have, and I regarded them as if they’d arrived in the mail. I could read them as surreal messages about stories I was writing. The embedded blank signs were reminders to interrupt the scene.

Sometimes Kelly collaged recognizable representations of people onto his postcards—his partner, Jack, and Marilyn Monroe were both among his recurrent subjects. Another Ellsworth Kelly card tacked to my board: Sailboat at Lake Pend Orielle, in which a grainy newsprint scrap featuring Goldie Hawn’s face obliterates the sailboat in the card’s caption. Kelly’s piece is dated to 1980, the year Hawn’s film Private Benjamin was released, and her wide-eyed expression looks like it was ripped from one of the publicity stills from the movie. In The Colossal Head of Harrison Ford, a black-and-white actor’s head looms blimp-like above a shoreline of beachgoers. While Ford is as obvious as a thought bubble, Kelly’s fragmentation of Hawn’s face makes it possible to see her in more anonymous terms, as I came to do in the months when the picture stayed on my wall. I thought of her more as a spirit in the lake, a presence, a visual of laughter itself. Living with it allowed her to exist for me as another abstraction: Unlike Ford’s visage, trapped in the weird balloon of its being, she was liberated.

Ellsworth Kelly, Horizontal Nude or St. Martin Landscape, 1974. Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, courtesy of the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin.

9

Sometimes Kelly flipped the landscape, as in a postcard of a painting of the Brooklyn Bridge, collaged on an image of his own nude body. More often he let facial features float out into forests. A freakish-looking pair of eyes are collaged into a stranger’s face that creeps beneath the Chateau Marmont, a haunting. Or he interspersed human elements piecemeal: Black pumps clopping along the beaches of St. Maarten. Wing tips kicking back on the sand. Torsos in the sky. Mouths cresting volcanoes. Butts over Brewster Flats. Body parts clothed and awkwardly intruding into exotic spaces, hovering over various bodies of water.

Kelly’s oversized and disembodied elements are the antithesis of a certain bad Instagram trope: the pedicured bare feet in x beautiful landscape, bonus points if the image includes a hammock, the blazing shade of nail polish that brags, I’m here, without really wishing you were too. Meanwhile, in one of Kelly’s postcards, a giant nose stuck into the hull of a sailboat whispers, But who the hell am I and why am I here?

“Ellsworth Kelly: Postcards” is on view at Matthew Marks in New York through June 25 and from August 27 through November 27 at The Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin. The exhibition catalogue is published by Delmonico Books/Tang.

Originally from North Carolina, Rebecca Bengal writes fiction, essays, and long-form journalism. She is based in New York City.

Copyright

© The Paris Review