The Taken Road Which Made All the Difference: Honouring the Legacy of Oxford’s Prominent Women

13 min read

13 min readHistory is much closer than we think, especially in a city like Oxford. The people of Oxford walk through history with each step they take on the cobblestone streets and with each student that goes to one of the many halls for their classes. However, history is not only architecture, but also those who made it happen. As such, it is important to bring to light and honour to those who are oftentimes known, but not acknowledged.

March is International Women’s History Month, and Oxford has seen its fair share of women who have fought to be more than simply footnotes in history. Through their actions, they have inspired or paved the way for other women to continue the journey towards an equal society. Though their actions might have been singular in nature, a personal fight, in the grand scheme of things, it is important not to only view them as such. While the women remembered here might not have known each other, their actions had an impact on each other’s lives. Just like the stones in Oxford’s beautiful architecture, their actions built upon one another and inspired other people to either add another stone or use those stones to create a staircase so that the women after them could stand at even greater heights.

It is an honour to be able to remember these women today. They might not have been the first to stand on the moon, but they saw that true change in society came from taking steps to push for equality. It is easier to tread on a path where one has an idea of where to go thanks to the guidance of those before you, allowing them to explore further and to continue to fight. This is how the women here are connected with one another – one’s actions inspiring another and thus creating women who fought for the change they desired to see.

Lady Margaret Beaufort

Tomb of Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII of England in Westminster Abbey. (Source: Feuerrabe / Wikimedia Commons / CC0)

Any college student in Oxford will have walked by Lady Margaret Hall in their daily life, or even attended it. But how many know the history behind the lady, whom the Hall is named after?

Lady Margaret Beaufort was the example of a strong and independent woman. A master of politics and charm, Lady Margaret managed to write her name in history as one of the most influential figures, after the royalty in power. It was through her efforts and behind-the-scenes manoeuvres, taking into account the unrest of the time and the political stage, that the first Tudor monarch came into power: Henry the Eighth. It would take a lecture or more to explain the details of her plans, but it can be summarised that her understanding of power dynamics allowed her to use marriages (most notably, that of her son and Elizabeth Woodville’s daughter) to solidify power between factions, and through her connection with different nobles, she managed to bring Henry to the point where he had the chance to defeat Richard III.

Her political influence is to be admired, as is being granted the title femme sole, which gave her the economic and self-independence that a woman of current time could possess, but Beaufort’s biggest contributions could be said to be her patronage of education and the arts. She commissioned the translation of different works, was herself a translator of works (Imitation of Christ, The Mirror of Gold for the Sinful Soul) and then donated and commissioned opportunities for many people to receive the education they deserved. While she funded the existence of another hall that opened its doors centuries after her death, in 1878 she was honoured by having the first women’s college in Oxford named after her.

Lady Margaret Hall, even in present days, remains a beacon for those who seek knowledge through an excellent education. It was only fitting, back in 1878, to name the first college for women after the woman who is to be remembered throughout history as a woman as powerful as a Queen, and yet not one. Her desire to spread knowledge and give others the chance for education enabled people to be inspired by her ambitions and continue her legacy for women who could grow to be just as strong and educated as she was.

To carry on the honourhonour of her legacy, Elizabeth Wordsworth was named principal of Lady Margaret’s Hall in 1879. She is the another important figure, who will be responsible for the creation of more opportunities for women to receive their education.

Elizabeth Wordsworth

Elizabeth Wordsworth (1840-1932), founder of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford and St Hugh’s College, Oxford. Photo from the archives of Lady Margaret Hall. (Source: Archives of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford / CC04)

Elizabeth Wordsworth is a name perhaps recognised by her statue on the stairs of the library at St. Hugh’s. Her story is worthy of such a statue, even if perhaps less known. She was educated at home, yet that did not stop her from gaining all the knowledge that a girl of her time could achieve by herself. She taught herself Latin and Greek, was an avid reader of The Iliad, which she read in both languages, and came from a family of scholars. It was this thirst for knowledge and desire for it that led to her becoming the founding Principal of Lady Margaret Hall, a position she held from its founding in 1878 until 1909. Her efforts for reaching more equality in education and closing the gap between men and women in terms of education did not stop at being the founding Principal. She was one of the first women to be called to the Hebdomadal Council in 1896, and while she did not believe in granting women degrees, perhaps due to internalised misogynistic views of the time, she did believe and fight for their chance at having an education equal to men.

During her tenure as Principal, Wordsworth was well aware of how even if it was a good step, there was still more to do. The students at Lady Margaret Hall still could not graduate there, and were granted a degree by Trinity College in Dublin. However, there were still many women who could not even receive the education they deserved, degree or not. The cost of education was high, and not affordable for all. As such, Wordsworth focused her strengths on founding another Hall, cheaper than the one where she was Principal, thus giving more women the chance to receive education.

St. Hugh’s was founded with the money she inherited from her father, and while it was originally aimed towards poorer women graduates, it has now grown into one of the largest colleges at the University of Oxford. Throughout the years, this college has provided an environment for all kinds of personalities to grow and take their first steps in academia. Notable mentions include famous Human Rights Barrister Amal Clooney, Theresa May, and many more. However, the spirit of the university’s founder shines through with one of its earlier students, Emily Davison, a suffragette who fought for the rights of women. Her determined spirit is perhaps the only reward a founder could need to see and feel that their creation had meaning.

Wordsworth’s time as principal and her founding of St. Hugh’s are acts that have etched her name in history as a woman who desired to create opportunities for all those who could not afford what was then the only option. She was a woman that inspired others to take charge and do what they could to make the world around them a fairer place for those around them. Wordsworth brought forth not only an equality in education, but also in socioeconomic classes, by giving women from all backgrounds the chance to attend college and receive an education.

Emily Davison

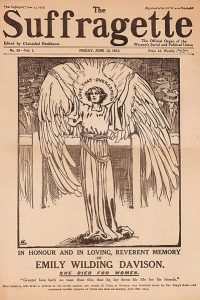

The front page of The Suffragette newspaper of 13th June 1913, which depicts Emily Davison as an angel. (Source: The Suffragette newspaper / PD)

Change never comes peacefully, nor is it handed to society on a silver platter. Thus, for society to grow and develop, there come people who rebel against the current system, finding freedom in fighting against the shackles that society demands to put on them. Emily Davison, a St. Hugh’s graduate, was one of these people. She was a suffragette whose determination to fight for equality was so strong that it even put her against fellow suffragettes, who did not support the uproar and trouble she would cause.

Her life was not easy, yet that did not stop her thirst for knowledge. In order to support her education and life, she worked as a governess and teacher. Both of those noble professions, which helped her afford St. Hugh’s, where she studied during her nights. She achieved first class honours, even if she could not graduate, as a degree was still not possible for a woman of her time. But her education in Oxford had achieved its goal of inspiring her drive for knowledge and fairness even more, as she identified with Geoffrey Chaucer’s tale The Knight’s Tale, a tale well known for its portrayal of the nobility of a knight. Wordsworth’s investment had not gone to waste, as it was only possible for Davison to afford her education through St. Hugh’s affordable fees, thus giving the chance for educational growth to such an inspiring woman.

Davison went on to become one of the most well-known suffragettes of her time, despite the unfortunate fact that many people only focus on her legacy, which was her manner of death. She left behind an example of someone who fought against injustice and would not sit idly for change to come. Davison fought for the world around her and for the generations yet to come, a sentiment she shared in her essay The Price of Liberty. She was a feminist and Christian, and these two facts are tightly intertwined in her identity and the way in which she saw the world: Davison was a strong believer in martyrdom, and her writing reflects Christian medieval ideologies and imagery, which also directly reflected her personal rhetoric and that of the suffragettes of the time.

During her life she was arrested nine times and on seven occasions went on a hunger strike. Yet, all that never stopped her from continuing to fight and rebel against society up until her death in the 1913 Derby as she walked on the field to strap a suffragette flag on King George V’s horse, who also was the reason for her death. Such a woman must be remembered for more than just her tragic passing, and it is with such that one must remember her relentless drive for the rights of women and how she let nothing stop her from fighting for it. “To lay down life for friends, that is glorious, selfless, inspiring! But to re-enact the tragedy of Calvary for generations yet unborn, that is the last consummate sacrifice of the Militant.” These are the words that Davison wrote in her essay mentioned above, and it is a testament of how when one fights for equality, they fight for the better life of those yet to come, a selfless pursuit.

These women and their legacy are built upon one another, one’s attempts leading to another’s success. Their history should not only be remembered and honoured during March, but rather throughout our daily lives. Just as them, there are many more women who deserve to have their story told and known. Women whose names are not remembered by many, but who have played a great role in shaping another’s life – mothers, sisters, and friends – all are united by the inherent desire of wanting to help one another. Change rarely comes from one person, nor from big acts. As the women above showed, often change comes from inspiring those after you. To change the world, you must lead by example and hope, fight for what is right and hope to see that new world bloom.

Our future depends on furthering their legacy and ideologies, for it is through learning from the past that we can see a brighter future ahead, and make sure to not repeat their mistakes and to add to the stones which they have already put down, raising the future generations to come in a better place than we are. Oxford, thus, has been, is, and will remain a cradle and place for women with potential and who want to make change happen.

Written and researched by MOX volunteer Sibora Sala.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.

Sources

Seward, Desmond (1995). The Wars of the Roses: And the Lives of Five Men and Women in the Fifteenth Century. London: Constable and Company Limited.

Gristwood, Sarah (2013). Blood Sisters: The Women Behind the Wars of the Roses. New York: Basic Books.

Jones, Michael K.; Underwood, Malcolm G. (1993), The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-5214-4794-1

Michael K. Jones; Malcolm G. Underwood (22 April 1993). The King’s Mother: Lady Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13ff. ISBN 978-0-z214-4794-2.

Brittain, Vera (1960). The Women at Oxford. London: George G Harrap & Co ltd.

Olivia Robinson, Alison Moulds (19 October 2016), Women in Oxford’s History: Elizabeth Wordsworth.

Lannon, Frances (2004). “Wordsworth, Dame Elizabeth (1840–1932)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

Crawford, Elizabeth (2003). The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-135-43402-1.

Colmore, Gertrude (1988) [1913]. “The Life of Emily Davison”. In Morley, Ann; Stanley, Liz (eds.). The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison. London: The Women’s Press. ISBN 978-0-7043-4133-3.

Davison, Emily (5 June 1914). “The Price of Liberty”. The Suffragette. p. 129.

Copyright

© Oxford University