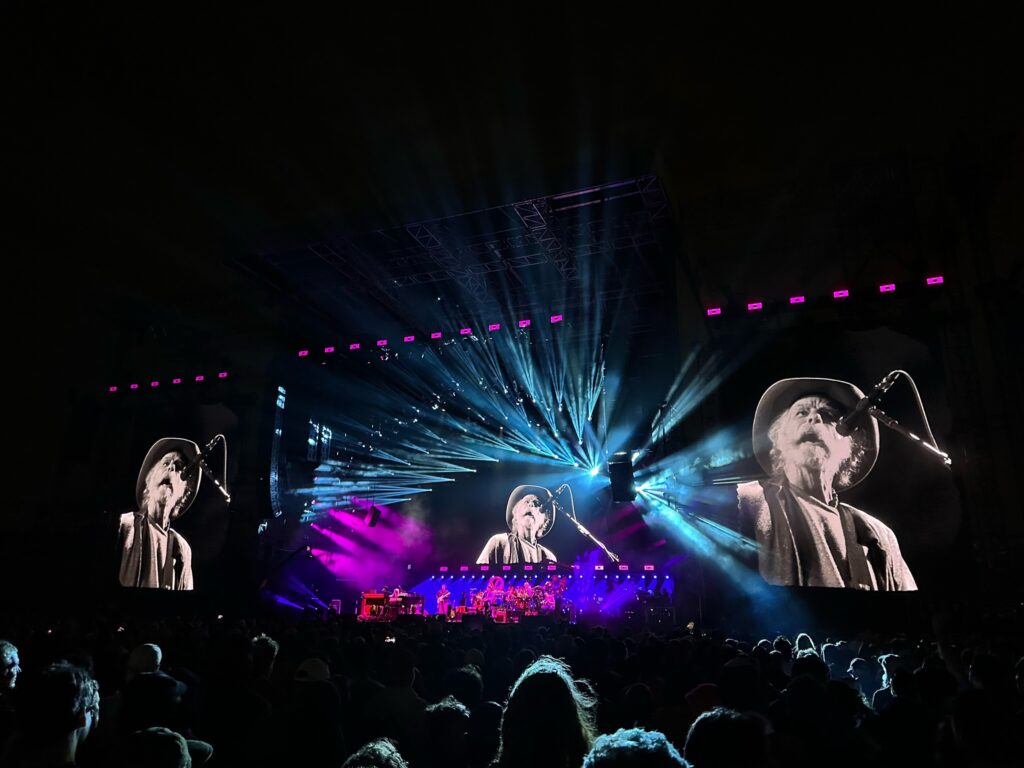

Black-and-white Bobby. Photographs by Sophie Haigney.

Let’s start with the dark stuff. On Saturday night in San Francisco, after the second-to-last-ever Dead & Co. show, every single ATM near the ballpark was apparently out of cash, because people couldn’t stop buying balloons filled with nitrous oxide, huffing them on the street for just a few more seconds of feeling high. The bars nearby were overrun, quite literally, long after everyone should have been at home. People go down at shows—it happened right in front of us one night, the medics rushing in and carrying someone out. There are, not infrequently, overdoses. There is too much of everything, sometimes. “I’m at that point in a bender where beer isn’t really doing anything for me anymore,” I heard someone joke on day three of the three-show run.

It is not that easy to drink yourself to death, actually, which I know because I have watched a lot of people try, but I could imagine it happening to many people in the context of the long slide of years or decades spent following the band. I always think “There but for the grace of God go I,” and I really mean it. So many people are dead and gone, among them the Dead’s lead songwriter, guitarist, and singer Jerry Garcia, who was killed by his own addiction to heroin at the age of fifty-three. “Do you think of Jerry as a prophet or a saint?” my friend asked me on Sunday as we got ready for the last show ever. The mood was elegiac, though the fact of finality wasn’t really sinking in, which might be why we kept repeating it over and over. “I can’t believe it’s really the last one,” someone said, not for the first time. “What are we even going to do next summer?” my friend lamented. “Are we going to like … have to get really into Phish?” “We are NOT getting into Phish,” someone else insisted, though we all agreed we would probably go see Phish at Madison Square Garden in August.

We put on our last clean Dead T-shirts—we were all running low and trading with one another—and headed back to the ballpark. A few of us had decided last minute to upgrade our tickets so we could be on the floor. I had never been on the floor for a Dead & Co. show; we always don’t spend the extra money and regret it later, so this time, one last time, we were not going to make that mistake. I said I wanted to hear “Bertha,” and we got it, right away, and right away we knew that every single member of the band was completely on, locked in. Bobby, as my friend observed, was “really cooking.” Jeff Chimenti, Oteil Burbridge, Mickey Hart, also cooking. And Mayer—I have never seen him, perhaps, cook like that, leaning into every moment harder than I have ever seen him lean, and he always leans in hard, given that he is probably among other things one of the greatest living guitarists.