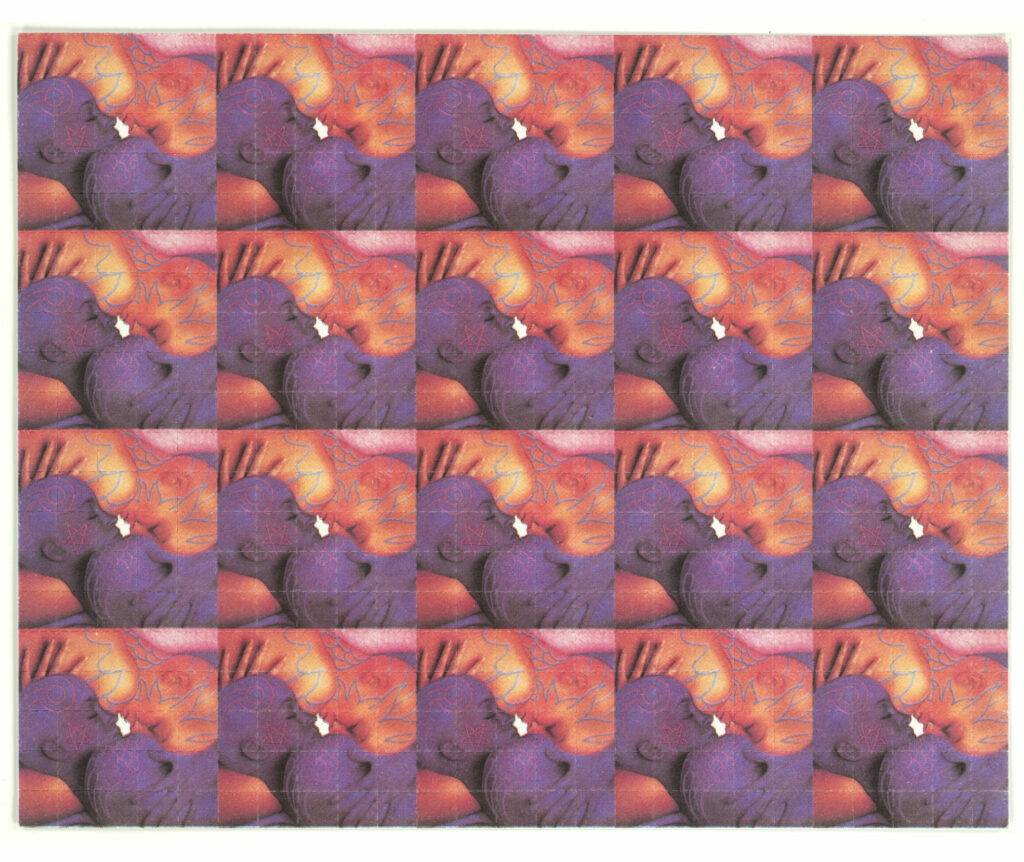

Alien Embrace, ca. 1996. Amsterdam, Netherlands.

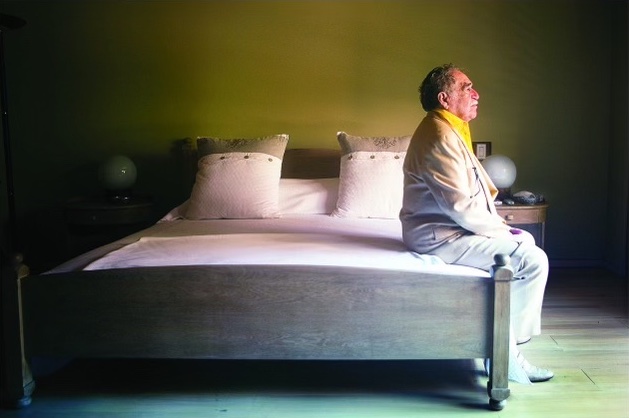

The Institute of Illegal Images (III) is housed in a dilapidated shotgun Victorian in San Francisco’s Mission District, which also happens to be the home of a gentleman named Mark McCloud. The shades are always drawn; the stairs are rotting; the door is peppered with stickers declaring various subcultural affiliations: “Acid Baby Jesus,” “Haight Street Art Center,” “I’m Still Voting for Zappa.” As in many buildings from that era, at least in this city, the first floor parlor has high ceilings, whose walls are packed salon-style with the core holdings of the institute: a few hundred mounted and framed examples of LSD blotter.

The III maintains the largest and most extensive collection of such paper products in the world, along with thousands of pieces of the materials—illustration boards, photostats, perforation boards—used to create them. Gazing at these crowded walls, the visitor is confronted with a riot of icons and designs, many drawn from art history, pop media, and the countercultural unconscious, here crammed together according to the horror vacui that drives so much psychedelic art. There are flying saucers, clowns, gryphons, superheroes, cartoon characters, Escher prints, landscapes, op art swirls, magic sigils, Japanese crests, and wallpaper patterns, often in multiple color variations.

Balancing this carnivalesque excess, at least to some degree, is a modernist sense of order. This announces itself principally through two core features of the blotter form: repetition and the grid. Many frames house full “sheets” of blotter: square or rectangular pieces of cardstock, printed and often perforated according to an abstract rectilinear grid demanded by the exigencies of blotter production. These grids are made up of individual hits or tabs, generally a quarter inch square or so and numbering anywhere from one hundred to four hundred to nine hundred units per sheet, depending on block size and design. While some sheets are illustrated with a single image that cloaks the entire grid, many assign the exact same figure to each hit, resulting in sheets that loosely resemble Andy Warhol’s canvases of Campbell’s soup cans. Other framed exhibits contain mere fragments from larger designs, sometimes nothing more than a single, hairy hit, perhaps the last extant example of a run from the eighties that has otherwise been literally swallowed up.

How to refer to all this paper? Users have called the stuff “blotter” or “tickets,” while police have used terms like “paper doses.” These days such pieces are often known as “blotter art,” a term that in many ways reflects the III’s own efforts to reframe this illicit ephemera into aesthetic objects (which is why I will stick to the more neutral “blotter”). There is another factor: over the last few decades, the blotter format has become a genre of popular art and a perfectly legal collectable. Though formally resembling their illegal forebears, editions of so called “vanity blotters,” undipped in LSD and frequently signed, are produced for collectors and casual fans rather than drug traffickers—who nonetheless can and do dose such wares when they need or want to. Though ignored by the larger art world, the vanity blotter market keeps on trucking, despite (or because of) the low cost of entry and a lack of critical valuation or collector apparatus.

Copyright

© The Paris Review