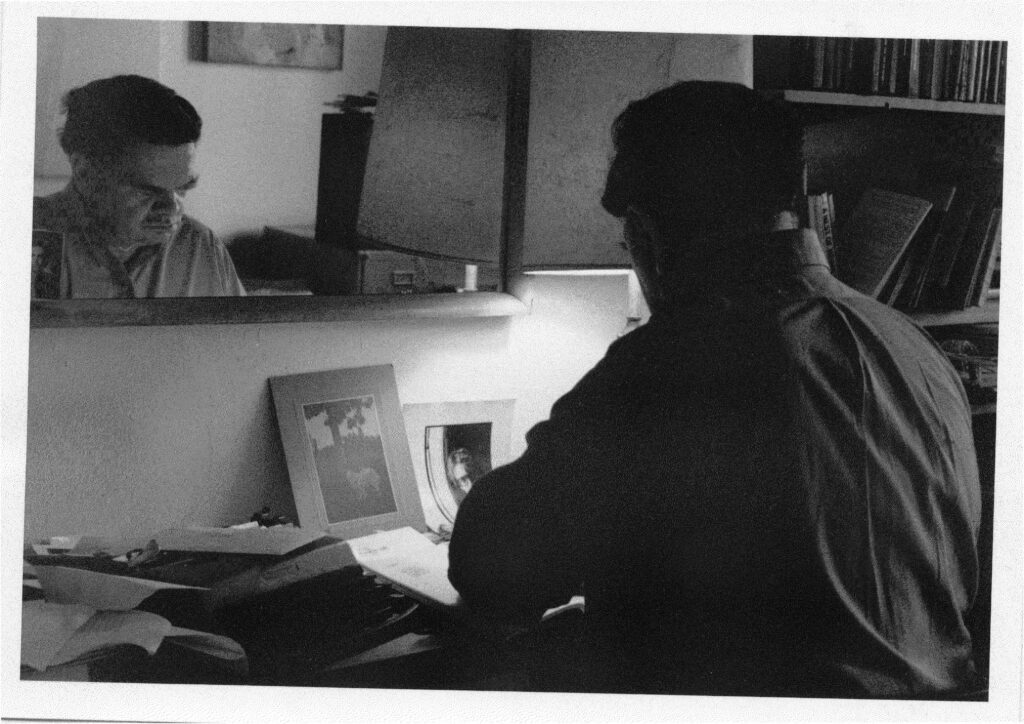

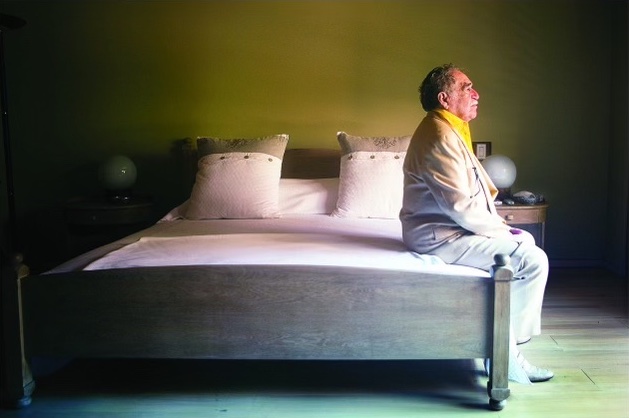

James Schuyler at the Chelsea Hotel, 1990. Photograph by Chris Felver.

I’d planned to write about one of my favorite James Schuyler poems in time for the centenary of his birth last November, but

Past is past, and if one

remembers what one meant

to do and never did, is

not to have thought to do

enough? Like that gather-

ing of one of each I

planned, to gather one

of each kind of clover,

daisy, paintbrush that

grew in that field

the cabin stood in and

study them one afternoon

before they wilted. Past

is past. I salute

that various field.

The tiny, beloved “Salute”—which is not the poem that I mean to discuss—both gathers and separates, does and then undoes what the poem says Schuyler meant to do but never did. (And isn’t this, the play of assembly and disassembly, to a certain extent just what verse is? How part and whole relate or fail to as the poem unfolds in time is a basic drama of poetic form.) Schuyler’s enjambments—at once distinct and soft, like the edge of a leaflet or the margin of a petal—are sites of hesitation where meanings collect before they’re scattered or revised.

For a second I hear “Like that gather-” as an imperative: Do it that way, gather in that manner, before the noun “gathering” gathers across the margin. I briefly hear “one of each I”—each of us is a field of various “I”s—as the object of the gathering before it becomes the subject who has “planned” it. (The comparative metrical regularity of “Like that gathering of one of each I planned,” the alternating stresses, haunts these enjambments, a prosodic past or frame the poem salutes and breaks with, breaks up.) I am always slightly surprised when “to gather one,” at the end of the seventh line, repeats “of each,” as opposed to modifying a new specific noun, at the left margin of line eight. (This break makes me feel the tension or oscillation between “each” and “kind”—and a kind is a gathering of likes—between the discrete specimen and the class for which it stands, the particular dissolving into exemplarity, when you write it down.)

Copyright

© The Paris Review