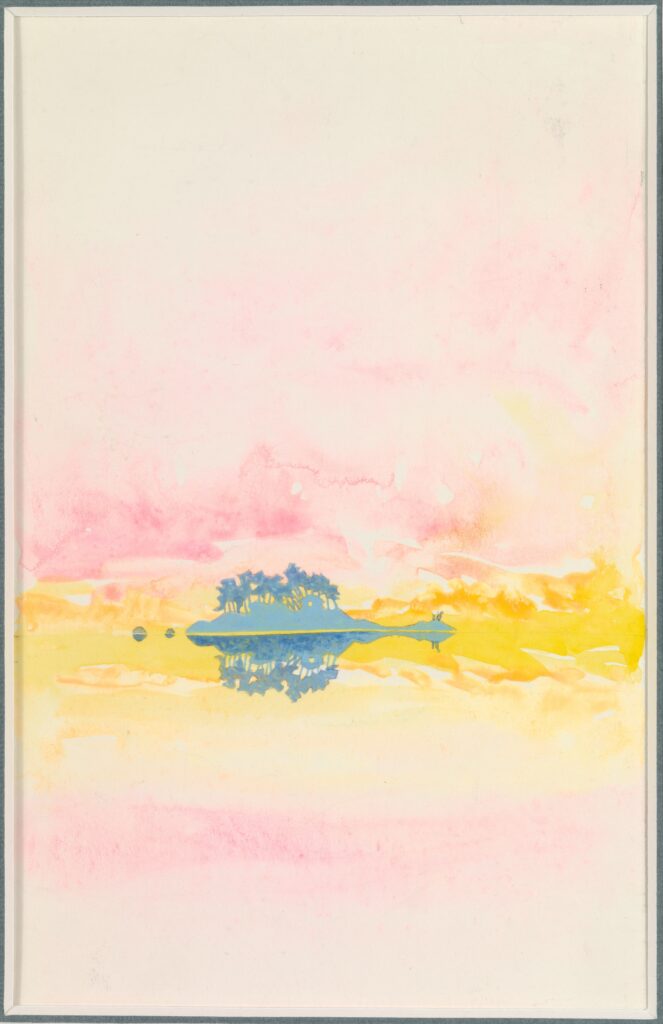

Berthe Morisot, On the Sofa, ca. 1882. Public domain.

In the months in which death swooped down on my father, circling on some days, and on others, its talons gripping the bars of the hospital bed where he lay dwindling, I found myself caught, as if on a Möbius tarmac strip, driving between Manhattan, where I live, New Haven, where I was teaching, and Long Island, where my father was dying. His death had been precipitated by a fall, but for years he had been kept alive by a series of red blood cell infusions; these had stopped working, and at almost ninety, one by one his faculties, until then intact, had one by one begun to fail. I had loved my father, but our relationship had not been an easy one, and his dying did not mitigate those complications nor make things easier between us. He was not a man who approved of my many casual arrangements and rearrangements or who participated in the give-and-take of ordinary life. He without fail believed he was right, but he also believed in portents and he was afraid of the dark. When I was a child his father died of the same blood disease that would kill him fifty years later, and early on the morning of that first death a flock of mourning doves alighted on the terraced lawn behind our house. Come and see, my father said. I was twelve, in my nightgown. A decade later, after my grandmother died, my father refused for the next ten years to sit in a darkened movie theater.

That fall, the autumn that turned into the winter of my father’s death, was for me more than usually fraught. A love affair had ended, or hadn’t—all that remained to be seen—but it meant that, as we were not speaking, he did not know that my father was dying, and I did not break our silence to tell him. A beloved dog, belonging to my middle daughter, a beautiful white Pyrenees, had developed epilepsy, which had resulted in seizures; during one seizure, the dog had badly broken her leg running into a tree; the decision was to put her down; my daughter, too, had a broken heart. I had an allergic reaction to my COVID booster, which resulted in a virulent raised rash all over my torso. And so on. Every Tuesday I drove eighty miles to New Haven from my house in Harlem, up the Saw Mill past Spuyten Duyvil and over to the Merritt Parkway, where the autumn leaves were so beautiful it was like driving up the bloodstream of a unicorn, and then from New Haven the next day one hundred miles to Long Island, over the Whitestone Bridge. My father had gout; he had pneumonia; he had dementia. He recognized me, or not. Afterward, I drove back over the Triborough to New York. The bridges were sutures over the bays and rivers. At the end of these trips I would park the car or put it in a garage a few blocks away from the house, climb up the stoop, go through the crowded little vestibule where steam hung in the air from the radiator, and then sit, still wearing my coat on the little sofa that was pushed against the wall. Sometimes I sat there for a few minutes, but more usually, I sat there for hours.

The sofa is a family relic. When I was first married, we found, in the attic space of a friend’s old chicken coop, the skeleton of a sofa. We were living in a tiny apartment on West End Avenue; the appeal of the forlorn sofa was that it was small. We brought it back in pieces tied to the roof of the car, and a few weeks later I had it re-covered with seven yards of pale silk twill embroidered with a pattern of pale red stripes and pink and yellow flowers: the choice of a person who has not yet had children or cats. A decade later the sofa moved to a larger apartment overlooking Morningside Park. By then I had acquired three children and a second husband, who conceived a deep dislike of the sofa, which he said was a Victorian copy of an early eighteenth-century design. There was a baby on the way. The brocade flowers unraveled. Laundry piled up on the sofa. When we moved to a drafty house down below the park, the sofa, now shreds, as the children liked to pick at the embroidery, was put between the windows at the end of the dining room until, in a frenzy of domestic renovation, it was shoved against the wall by the front door.

A peculiarity of the house to which we moved is that it is only fifteen feet wide. Sitting on the sofa in my coat, still as a figure hacked from stone, I looked almost directly into a corner formed by the back of another sofa, the curve of the piano, and the dim recess of the fireplace, encased in black slate. A space of no space. Before my father’s fall that summer, I was in Rome, walking almost every afternoon from Monti, near the Colosseum, east through the Porta Pia and then down to the Via delle Quattro Fontane and then to the river. The Italian architect Francesco Borromini, who often built in almost impossible configurations and made the air in those spaces eddy as if awhirl with swallows, was a master of liminal space, of small bivouacs, places to secret the self. Standing across the street and gazing at the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, it is difficult to see the entire facade from the street, jammed in the intersection of four streets. The visitor enters through a green door into a tiny elliptical anteroom that shudders open to the small nave; above, an oval full of light, punctuated by embossed diamonds and hexagons, lifts up the space of the church like a kite held aloft by the sky at the end of a string. Often there are students drawing in the pews, their necks craned upward. Sometimes I would sit there, too. My father was not a handy man, but one of the things he did make for me were kites out of newspaper, and I could imagine those kites swooping above the nave as they had swooped and veered over Riverside Park, the newsprint too far away to read. When I first came to Italy, when I was very young, I lived in Perugia, down one of the streets winding from the piazza, and every night we came to sit by the fountain, where at dusk the starlings spiraled above it like a column of ash and then flitted back down to eat the crumbs of bread we left for them.

Copyright

© The Paris Review