Monroe in Don’t Bother to Knock (1952), from the July 1953 issue of Modern Screen.

“It’s good they told me what / the moon was when I was a child,” reads a line from a poem by Marilyn Monroe. “It’s better they told me as a child what it was / for I could not understand it now.” The untitled poem, narrating a nighttime taxi ride in Manhattan, flits between the cityscape, a view of the East River, and, across it, the neon Pepsi-Cola sign, though, she tells us, “I am not looking at these things. / I am looking for my lover.” The very real moon comes to symbolize the confusion of adult experience. I quote these lines back to myself when I feel acutely that I understand less, not more, than I used to.

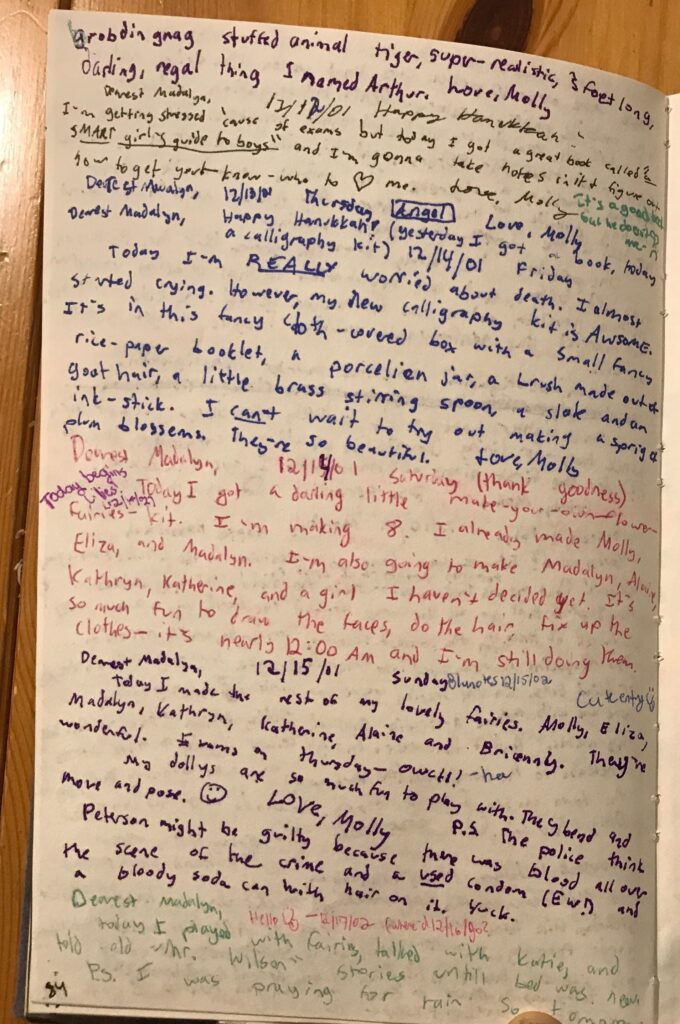

The poet Marilyn was the first Marilyn I encountered. Like her when she was young, I lived in a strict Pentecostal environment that forbade much of pop culture, but unlike her, I didn’t gorge myself on movies after escaping the prohibition. Although I had heard of “Marilyn Monroe,” I hadn’t yet happened to see any of her films when I came across Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters by Marilyn Monroe in a bookstore. I, like so many, fell for the allure—still, to me, a forbidden one—of her image: Marilyn on a sofa seemingly caught looking up and away from the black notebook in her lap. Her expression suggests she hasn’t yet decided whether the distraction is a source of apprehension or delight. Wearing coral lipstick and a black turtleneck, she is beautiful and bookish. The apparently candid photo is actually from a 1953 series for Life by the photojournalist Alfred Eisenstaedt. Then twenty-six, Marilyn was famous, and only becoming more so: she’d started dating the baseball star Joe DiMaggio. The revelation that years before she’d posed nude for a calendar (and wasn’t ashamed) had recently scandalized McCarthyite America. Life’s portraits of a sex symbol among books play to an audience’s wish to condescend to the object of their desire, to laugh at the “dumb blond” who thinks she can read. (Desire, after all, is an involuntary subjection often trailed by resentment.) As always, Marilyn insisted on approving the images; the contact sheets show her red pen. And in this photo, whatever anyone else intended, I also see her considered self-creation.

Marilyn’s poems are, as the book’s title indicates, mostly fragmentary. Rarely (if ever) did a first draft become a second, but themes and motifs recur as though being reworked. They were written in notebooks and on scrap paper alongside lines of dialogue from her films, song titles, lists, outpourings of anxiety, and accounts of both real events and dreams. Sometimes lines that read like poems actually aren’t, as with some of the notes made during her years spent in psychoanalysis and in classes with Lee Strasberg, a controversial proponent of the “Method,” a technique that demands actors dig deep into their emotions and memories in order to fully inhabit their roles. Some of Marilyn’s pages are tidily penned, starting precisely at the red vertical margin, but often the poems and notes range across or even around the page, with words crossed out and sentences connected by arrows. Because the lines often end where the paper does, it’s not always obvious where they break, or whether they should break at all. According to Norman Rosten, a poet who became better known for being a friend of hers, “She had the instinct and reflexes of the poet, but she lacked the control.”

Marilyn left high school when she married her first husband and, aside from a continuing-education course in literature at UCLA, never had further formal education. But she was a committed if haphazard autodidact, going to a now-defunct bookstore in Los Angeles to leaf through and buy whatever books interested her (Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, for instance). Although the playwright Arthur Miller, her third husband, claimed she never finished anything “with the possible exception of Colette’s Chéri and a few short stories,” others contradict this. She professed a love for The Brothers Karamazov and a wish to play its central female character, Grushenka. Her library contained more than four hundred books, including verse collections by D. H. Lawrence, Emily Dickinson, and Yuan Mei, and an anthology of African American poetry.