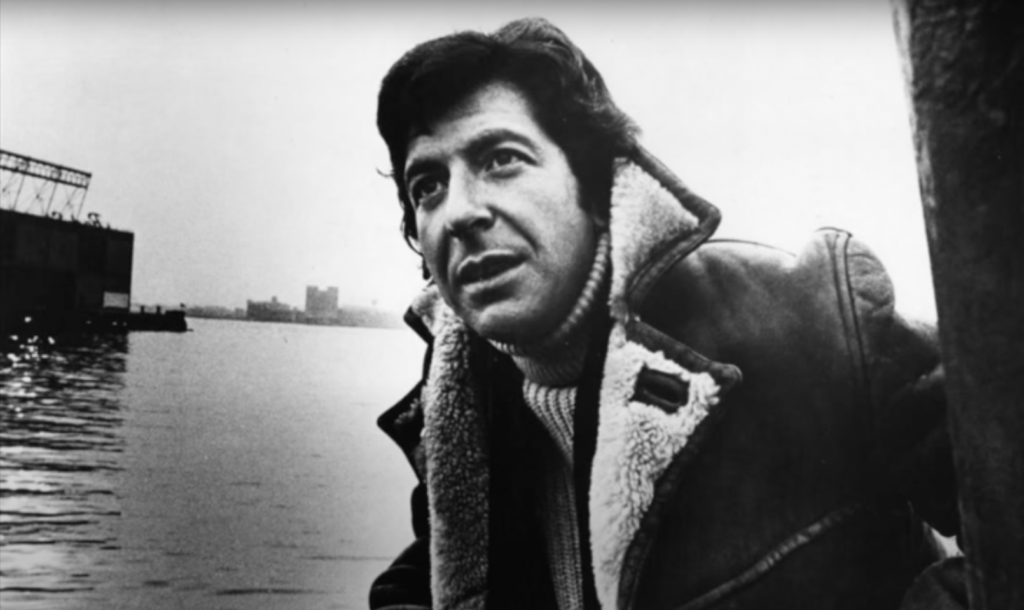

Beautiful Losers: On Leonard Cohen

To mark the appearance of Leonard Cohen’s “Begin Again” in our Summer issue, we’re publishing a series of short reflections on his life and work.

In December 1981, I visited my older brother at the University of Michigan. There three men taught me to play three songs on guitar: “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You,” “Genesis,” and “Suzanne.” The first left me cold. The second, its melodic charms notwithstanding, featured the line “They say I’m harder than … a marble shaft,” leading me to believe, until just now when I finally looked him up, that Jorma Kaukonen was born in Finland and never really learned English. The third rocketed me, on my return to William & Mary, straight to the town record store, where the cashier sold me Songs of Leonard Cohen with a money-back guarantee on the condition that I listen to it ten times before complaining.

There existed milieus where Cohen’s music was inescapable, such as kibbutzim and the GDR. Tidewater, Virginia, was not that milieu. A basic tenet of its all-pervasive racism was that white people couldn’t do music. Black people were denied decent jobs and homes, but there was no question that high school dances would be themed “Always and Forever” and culminate in “Brick House” and “Flashlight.” At college, surrounded by northern suburbanites’ awkward skanking to babyish punk rock, I realized that I had been inadvertently blessed. But it did take me at least ten listens to acclimate to Cohen’s chansonnier velocity and compound meters while his lyrics were sinking their claws into my soul.

I taught myself all the songs on the record and borrowed his novels from the library. An image of sainthood from Beautiful Losers haunted me for decades: to live like a runaway ski. I blame The Favorite Game for the image of a sentient vibrator that drives a couple from their home, as well as a description of getting trapped in a writhing mass of young people at a political rally but failing to orgasm. I suspect they’re also from Beautiful Losers. The Favorite Game is about getting laid a lot in swinging Montreal (autobiographical).

I preferred the songs, which restored the human dignity the novels attacked. I remember singing “Why are you so quiet now / Standing there in the doorway” while a housemate I had a crush on stood quietly in the doorway. For once we were in each other’s presence yet not acting like idiots, our dopiness suspended by the schematic innocence of a simple song—transfixed by poetry, lost in the timeless intimacy of two people listening to one of them perform the beauty of someone else.

Then time resumed, and soon afterward he plunked down on my bed unannounced, not to sing “You Know Who I Am,” but to plead his stunningly counterproductive case for sex with me, citing what he saw as my indiscriminate promiscuity. I think the last time I saw him he was either cooking shirtless or staring at me across a dance floor, dressed as a pumpkin. Life could be so lyrical, if it weren’t a novel.

Nell Zink has published six novels, including the recent Avalon.

Copyright

© The Paris Review