Sheila Heti and Kathryn Scanlan Recommend

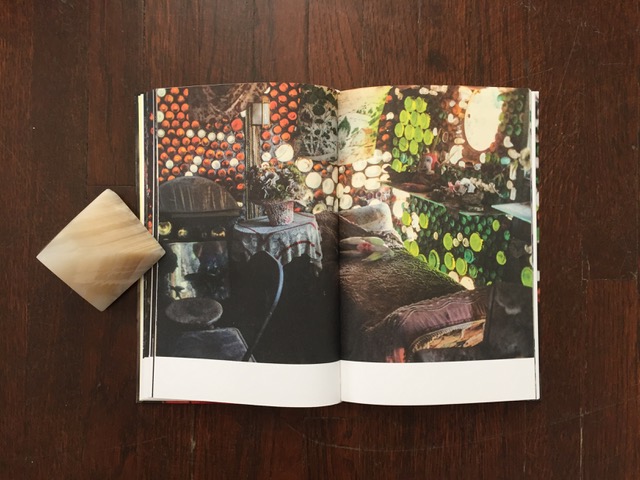

Kathi Hofer: “Grandma” Prisbrey’s Bottle Village, published last year by Leipzig’s Spector Books, is a nice-looking hardback about the vernacular art environment Tressa Prisbrey built in Santa Susana, California, a former railroad town now incorporated into Simi Valley. The volume was compiled, introduced, and translated into German by Hofer, an Austrian artist who first encountered Prisbrey’s pencil assemblages in an exhibition at the Los Angeles Public Library.

Prisbrey, the daughter of German immigrants, was married at fifteen to a man almost forty years her senior; they had seven children together before she left him and began an itinerant life with her kids in the late twenties. When she finally settled in Santa Susana in 1946, she met her second husband, and together they bought a plot of land, about a third of an acre in size, which they leveled and was where they parked their trailer after removing its wheels. Prisbrey began building the Bottle Village in 1956, at the age of sixty. Looking for a way to improve the property—to “make it pay”—she chose bottles as a building material because there were plenty of them around, and made daily trips to the local dump to collect other materials. She planted cacti everywhere—hundreds of varieties—because they are “independent, prickly, and ask nothing from anybody” and because, she said, “they remind me of myself.” Her sons handled roofing and doors, but otherwise, every structure in the Bottle Village—sixteen houses total—was built by Prisbrey. For years, she gave guided tours for a small admission fee, and children were often preoccupied by Prisbrey’s white cat and her kittens, who had their own Prisbrey house made from the nose of a plane and whom Prisbrey combed with food coloring: pink, green, and yellow animals roamed the place.

She left it, finally, in 1982, at the age of eighty-six, and died in 1988. But the site, though in disrepair, remains and is protected as a historical landmark. Hofer’s book—an elegant intervention and homage—includes texts, color photographs of the Bottle Village, and a facsimile edition of the essay Prisbrey wrote about her creation in 1960, which she published as a pamphlet and gave (or mailed) to anyone who asked. Reading Prisbrey’s charming, conversational descriptions of her village, you get a sense of what it might’ve been like to tour it with her, and how important that social aspect was to the project. “Oh, this is an interesting place to see,” she says, “and you hear such funny things, too.”

—Kathryn Scanlan, author of “Backsiders”

I hope Brett Lockspeiser and Joshua Foer google themselves, because I have wanted to thank them for creating Sefaria, an open-source site and app which collects texts from three thousand years of Jewish thought, as well as important rabbinical commentaries. It’s free, the presentation is so simple, and you can really feel the historical consciousness behind the whole project. Their “About” page reads: “We are the generation charged with shepherding our texts from print to digital in a way that can expand their reach and impact in new and unprecedented ways.” A simple thought, but that statement really moves me: seeing oneself as part of a generation among generations, each with its own task.

Then there is Marlen Haushofer’s The Wall, which I read last year and have thought about every day since. New Directions is reissuing it this summer. It was written in German in 1963 and follows a woman who finds herself suddenly separated from the rest of society by a transparent wall that appears one day, very tall and very long and dug into the ground; she cannot get around it and does not know how it came to be there. It is about our reasons for living, self-sufficiency, solitude, men, women, war, and love, and the problem of other minds. And the animals in this book—oh! I don’t understand why this book is not considered one of the most important books of the twentieth century. I have been anxiously pushing it on everyone I know, and now I push it on you.

—Sheila Heti

You can read Sheila Heti’s interview with Caren Beilin on the Daily here.

I’m prone to blaming “seasonal change” for my mood, saying things like, “I’m feeling weird, but maybe just because it’s March.” There might be something to this; there might not. It’s an imprecise kind of astrology that makes me feel porous to the world around me. Well, spring makes me sad. Something about the lengthening evening light, the cold but sunny days, the constant promise of rain—it reminds me of the school year ending, of things coming to a close. Then again, spring also makes me elated: all those flowering trees.

Nancy Lemann’s novels are meant to be read in times of seasonal change, when one is in a mood. They’re full of mood swings and other dualities: North/South, revelry/despair, flowers/decay. A woman might be talking about the hat she wore when she was fifteen, but really she is talking about her dead son. Parties go on for far too long and then start up again. Lemann is one of those writers whose work always seems to be circulating through recommendations—people asking each other online or over drinks whether they’ve read Lives of the Saints, her lush New Orleans novel. (Who started this? As with Cassandra at the Wedding, it’s hard to say—women with good taste?) Lives of the Saints is madcap and funny and sad and, for my money, contains some of the best pairs of sentences, one-two punches, and crazy transitions in fiction.

In November, which was a difficult month for me, and which is maybe always a difficult month for me, and which is likely a difficult month for a lot of people, because winter is starting and there’s nothing to be done about it, I got into bed and reread Lives of the Saints in a single day. It was one of the more luxurious experiences of my life. Then I ordered Lemann’s other novels, all of them, though not all were in print, so it required a bit of searching. I read The Fiery Pantheon, which is even more madcap and less plotted than Lives of the Saints, but full of the same odd brilliant lines and true eccentrics, the same fixation on the North and the South, doomed romance, and crumbling buildings. Then it was really winter, and I put the books aside. Now, though, it’s almost spring—no, it really is spring, we’ve already slipped past that near-invisible moment of transition—and I’ve started reading her book Sportsman’s Paradise. It’s about summer weekends away in Orient Point, but it’s all digressions, which is what long summer weekends are. Suddenly we are talking about baseball:

There is something dashing and brave about the huge cavernous stadium with its excessive quality, I mean its excess, too many people, claustrophobic, as the stadium is a swirling madhouse of chaos … What I like best is when the young men come straight from work, in their suits and ties and sunglasses, emanating a certain gentility or plain American history. They in pairs or threes. Brave of them to withstand the heat and the chaos, for the sake of their innocent sport, and dashing of them in their cavernous unlovely stadium, in the bad conditions, losing. The gallantry of their broken dreams and shining hopes in each situation, such as the double-header Friday night.

Once again: it’s the season!

—Sophie Haigney, web editor

Copyright

© The Paris Review