Re-Covered: I Leap Over the Wall by Monica Baldwin

In Re-Covered, Lucy Scholes exhumes the out-of-print and forgotten books that shouldn’t be.

Ten years after Monica Baldwin voluntarily entered an enclosed religious order of Augustinian nuns, she began to think she might have made a mistake. She had entered the order on October 26, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the World War I, when she was just twenty-one years old. At thirty-one, she hadn’t lost her faith, but she had begun to doubt her vocation; the sacrifices that cloistered life entailed did not come easily to her, and unlike many around her, she hadn’t experienced a “vital encounter” between her soul and God. Eighteen years later, she finally knew for sure: it was time to leave. Granted special dispensation from the Vatican to leave the order but remain a Roman Catholic, Baldwin—who was now forty-nine years old—quit the only adult life she’d known, that of the “strictest possible enclosure,” and emerged back into the world in 1941, into a world that had just plunged, once again, into war.

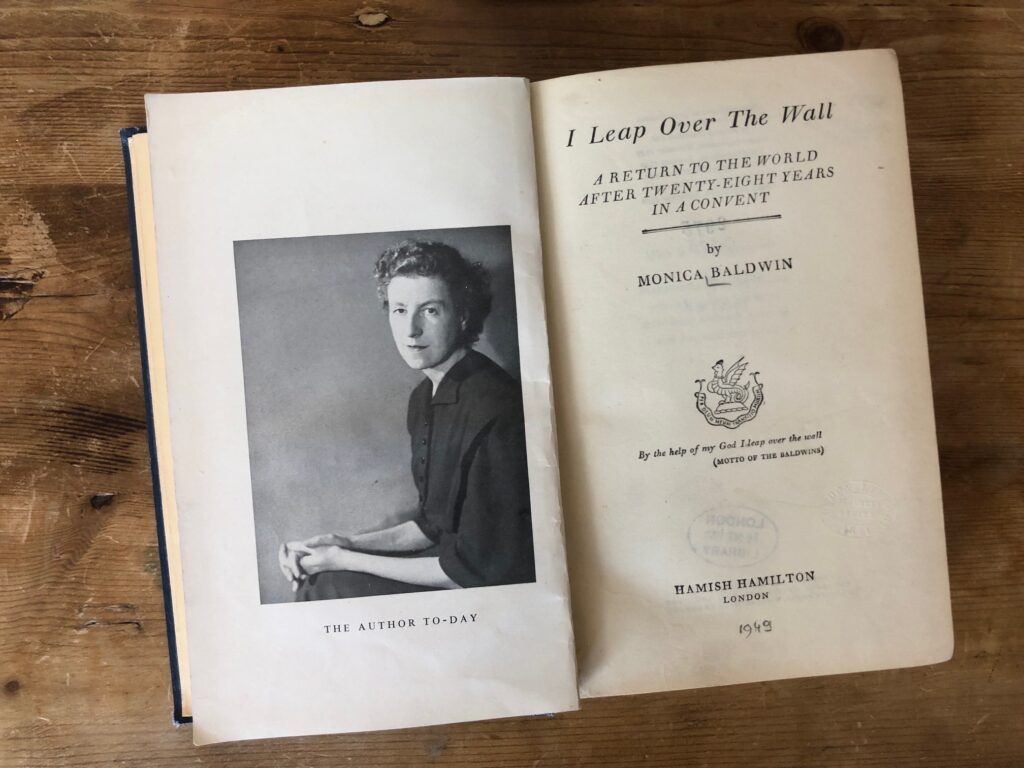

Baldwin relates the trials and tribulations that followed in her delightful memoir, I Leap Over the Wall: A Return to the World After Twenty-Eight Years in a Convent. A best seller on its initial release in 1949, it won its author plenty of fans—including the film star Vivian Leigh, who named Baldwin’s book as one of her four favorite titles published that year, in the Sunday Times. It has been reprinted on a number of occasions since. All the same, its popularity has waned over the years, and it’s not a book mentioned often today. I picked it up again as I began my own reentrance into the world, after two years of lockdowns, isolation, and quarantine.

It would be wrong to draw too many parallels between Baldwin’s experience and mine, though. Whereas the hiatus in our lives now has been a largely shared ordeal, the marvel of Baldwin’s situation is its singularity: she missed the entire world between the wars while life went on. Her portrait of Britain in wartime is therefore unique. She’s like an alien visiting Earth, taking nothing around her for granted; it’s all equally fascinating, from the rows of “hatless” young women sitting on trains and smoking cigarettes with their “padded shoulders and purple nails,” to the ravioli she nervously orders from a café lunch menu that seems to her written in gibberish. (When the meal arrives, she remains just as confused—it “might have been anything from cats’ meat to fried spam,” she attests, bemused.) We’re used to accounts of life on the home front that are steeped in the “keep calm and carry on” wartime mentality, so it can be hard to find those that convey the sheer incongruity, as Baldwin’s does, of the experience of a world turned uncanny. This is not to say that I Leap Over the Wall could quite be described as an eerie or a haunting book—if anything, Baldwin’s portrait of a country during one of its darkest hours is lit with an oddly wondrous naivete. Nevertheless, she captures a world turned upside down and inside out, one in which everyone feels displaced and unmoored, and which she observes with eyes wide open. She had spent twenty-eight years trying to disengage from life. “You can’t be completely wrapped up in God (and he is a jealous lover) unless you are unwrapped-up in what this world has to offer you,” she explains. “In convents, this process of unwrapping is effected by a system of remorseless separation from everything that is not God.” Thus her return to the world, which necessarily forces her to “sit up and take notice of what was going on,” nearly drives her crazy.

***

Baldwin begins her story by describing in detail the camiknickers, brassiere, and sheer silk stockings with which her sister presents her on the morning that she leaves the convent. These are responsible for the first of the “crescendo of shocks” following her release. Not only are these garments unimaginable to her by the standards of those in the convent, where she had worn the thick, scratchy full-body serge shift donned by nuns since the fourteenth century, heavy petticoats, and cumbersome stockings “the shape and consistency of a Wellington boot,” they also bear little resemblance to anything she remembers from her Edwardian youth. The surprises continue.

A twenty-eight-year absence from the world at any point in history would undoubtedly be destabilizing, but Baldwin’s coincided with a period of particularly astonishing social, political, and cultural transformation, especially in the UK. World War I occasioned significant turmoil in all areas of life; in its aftermath, the rigid class system that had previously defined British society disintegrated, women won the right to vote, huge scientific and medical advances were made, and even the borders of the wider European map were redrawn. Whole empires had crumbled. When, on Baldwin’s first night of freedom, someone switches on the radio after dinner at an aunt and uncle’s London home, it’s all she can do to not “fly from the room, shrieking ‘Witchcraft!’ ” She’s as discombobulated as the somnolent protagonist of H. G. Wells’s speculative novel When the Sleeper Awakes (1899), who finally stirs from his 203-year nap to find that he’s been transported from the nineteenth to the twenty-second century. Baldwin herself makes a different analogy, drawing from her childhood: she repeatedly likens herself to Rip Van Winkle.

That Baldwin’s cultural references are confined to that material deemed suitable for a well-born young lady in Edwardian England makes for some entertaining confusion. But, aware of her limitations, she sets about a brisk reeducation program. Novels, she confesses, are enlightening (once, that is, she’s managed to translate the modern slang), but newspapers have the unfortunate effect of making her feel “particularly idiotic.” She complains that even the book reviews are packed with “incomprehensible” clichés and allusions. Social historians of the interwar period could spend years combing newspapers, newsreels, and periodicals of the day, collating a list of the cultural touchstones of the era, but Baldwin does the same work for us in a matter of only two sentences:

I had never heard of the Unknown Soldier, Jazz, Isolationism, Lounge lizards, Lease-Lend, Cavalcade, Gin-and-It, Vimy Ridge or the Lambeth Walk; neither did the words Nosey Parker, Hollywood, Cocktail, Robot, Woolworth, Strip-tease, Bright Young Thing, convey anything to my mind. Unknown names, too, were always cropping up: Epstein, Schiaparelli, James Agate, Greta Garbo, Picasso, D. H. Lawrence and Dr. Marie Stopes …

Her first Disney film is quite the revelation. As is her first dry martini!

She documents her steep learning curve with both an eloquence and a pitch-perfect comic timing that’s unexpected from someone who’s spent the majority of her adult life in enclosed, sanctified, silent contemplation. And there’s amusement to be found in the revelation that this precise silence, prized above all else in the convent, now makes her something of a nuisance. While staying with another aunt and uncle, she learns that she has what others would describe as “an irritating habit of opening doors so quietly that nobody knew when I had entered a room.” After the household tires of her creeping soundlessly about the house, suddenly materializing behind them when they least expect it, Uncle Stan—as in Stanley Baldwin, who, during his niece’s absence, has been thrice prime minister of Britain—takes her aside for a quiet word. “Before a fortnight was ended,” Baldwin cheerfully reports, “I had taught myself to stamp up and down stairs, rattle door handles and bang doors in such wise as to make my presence felt by everybody in the vicinity.”

Baldwin may be struggling to get to grips with the modern world, but, as it turns out, the life that she’s left behind proves just as incomprehensible to those outside the convent. She tries to explain to friends that one of the most shocking things about the outside world is the stranglehold that food has over everyone’s life. To eat beyond what is absolutely necessary would, in the convent, be regarded as gluttony. And part of every nun’s noviceship is being taught to “mortify one’s palate”—whether by eating something one doesn’t like, refusing something one does, not drinking or eating when one is thirsty or hungry, or, in extreme cases, eating the scraps that would otherwise be deemed inedible and thrown away. Her interlocutors are in equal parts bewildered and revolted. “It was like trying to discuss radar with a goldfish,” she reports.

***

Though some warn her that the “crazy turmoil” of wartime is not the best moment to reemerge into everyday life, Baldwin recognizes that the confusion occasioned by international conflict also allows her to find common ground with others—and to observe the world around her, mostly unnoticed. “How easy it would be,” she writes optimistically, “to plunge into the seething waters of the war deluge and splash about unnoticed, listening, looking about, experimenting, learning about things, till the floods died down!”

The world she enters, of course, has already been made unfamiliar by war. Even the physical environment is uncanny: ripped-apart ruins of Blitz-bombed buildings have turned once recognizable streets into unknown terrain; the names on railway stations have been painted out; park railings have been removed, smelted down, and turned into weaponry.

Early on, she describes herself as “a being with no background,” a feeling that might have been shared by many—in Britain, Europe, and beyond—during these years, not only by those struggling on the home front, or by the soldiers who found themselves deployed across the globe in unknown territories, but most of all by those hundreds of thousands of displaced persons made refugees by either advancing troops, physical destruction, or hatred. “I have sometimes wondered whether there may not be some vague, physical sympathy between the rootless members of the human race; those who have been completely severed from their backgrounds by the guillotine of circumstance,” Baldwin perceptively and movingly writes later in the book, when describing a connection she forges with a soldier whom she meets while working as a skivvy in an army canteen. This soldier friend had recently lost everything when a land mine fell on his house: his home, his possessions, and every single member of his family—his parents, his sisters, his wife, and their three small children. It was a loss of such incomprehensible magnitude that Baldwin recognizes it has bestowed on him a “terrible loneliness.”

And indeed, a current of loneliness courses through this book, too, beneath its optimism and picaresque-style escapades. The descriptions of the days Baldwin spends trudging the streets of London in the pouring rain—often getting hopelessly lost, being rejected for one job after another (each application sunk due to her lack of qualifications or training), and hunting for lodgings cheap enough for her meager budget—bring to mind the most desolate moments of Jean Rhys’s novels about down-and-out women in London between the wars, or even those myriad homeless citizens forced to wander the streets during the Great Depression that Helen Zenna Smith depicts so candidly in Shadow Women (1932) and Luxury Ladies (1933), the sequels to her famous First World War novel, Not So Quiet … (1930). Baldwin’s age adds another dimension to the bleakness of her situation; in its darker moments, this memoir might be read as a portrait of the invisibility and isolation of that long put-upon and looked-down-upon figure: the middle-aged spinster. But, as every reader of the English classics knows, one underestimates such women at one’s own peril. Baldwin certainly wasn’t someone easily vanquished, as proven by the title of her second memoir—published in 1965, when she was in her early seventies—Goose in the Jungle: A Flight Round the World with Digressions.

Lucy Scholes is a critic who lives in London. She writes for the NYR Daily, the Financial Times, the New York Times Book Review, and Literary Hub, among other publications. Read earlier installments of Re-Covered.

Copyright

© The Paris Review