This essay originally appeared in Reframed, the Art in America newsletter about art that surprises us and works that get us worked up. Sign up here to receive it every Thursday.

The French polymath Jean Cocteau (1889–1963) was never content to work in one mode—and was ostracized for it. His retrospective at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice is titled “The Juggler’s Revenge”: it makes a case for this versatility, showing a cohesive spirit across works in film, sculpture, collage, drawing, literature, and jewelry.

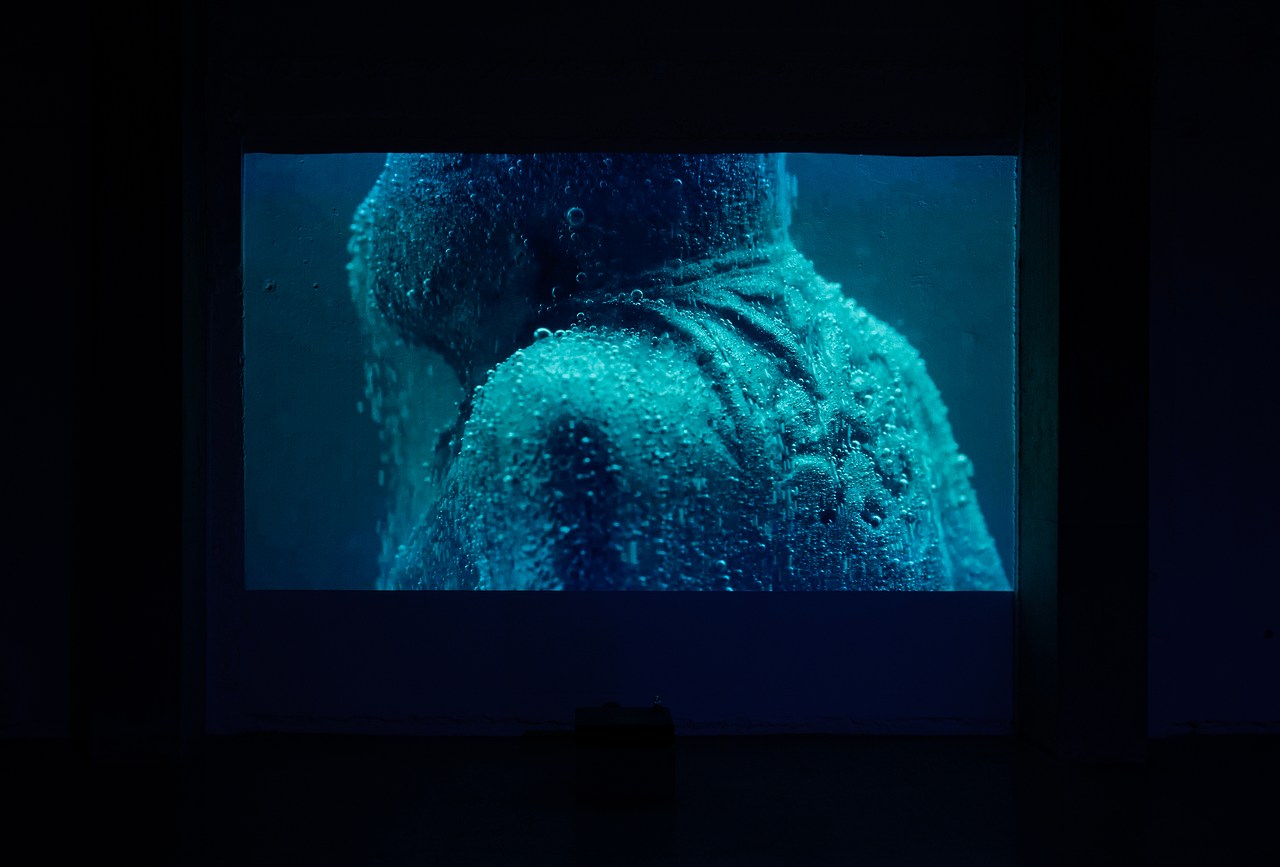

No bother, Cocteau was unperturbed, impressively juggling this range of media. He inflected even his most commercial films with avant-garde impulses. An excerpt from his 1930 Surrealist film Le Sang d’un poète (The Blood of a Poet) features a handsome shirtless man communing with an anthropomorphic armless Classical sculpture. At one point, the man finds a pair of animate lips on his palm, which he then transfers to the sculpture. The sculpture, now equipped with a mouth, instructs the man to go through the looking glass, so he positions himself along its frame and presses his body against it. Suddenly, he splashes through, as if into a swimming pool, and falls into the abyss.

By 1953, Cocteau served as the jury president for the Cannes Film Festival, a post he held two years in a row. But André Breton, Surrealism’s self-appointed gatekeeper, “despised Cocteau,” the catalog reveals—not on the quality of his work, but on the simple fact that Breton was a raging homophobe, describing himself as “completely disgusted” by male homosexuality.

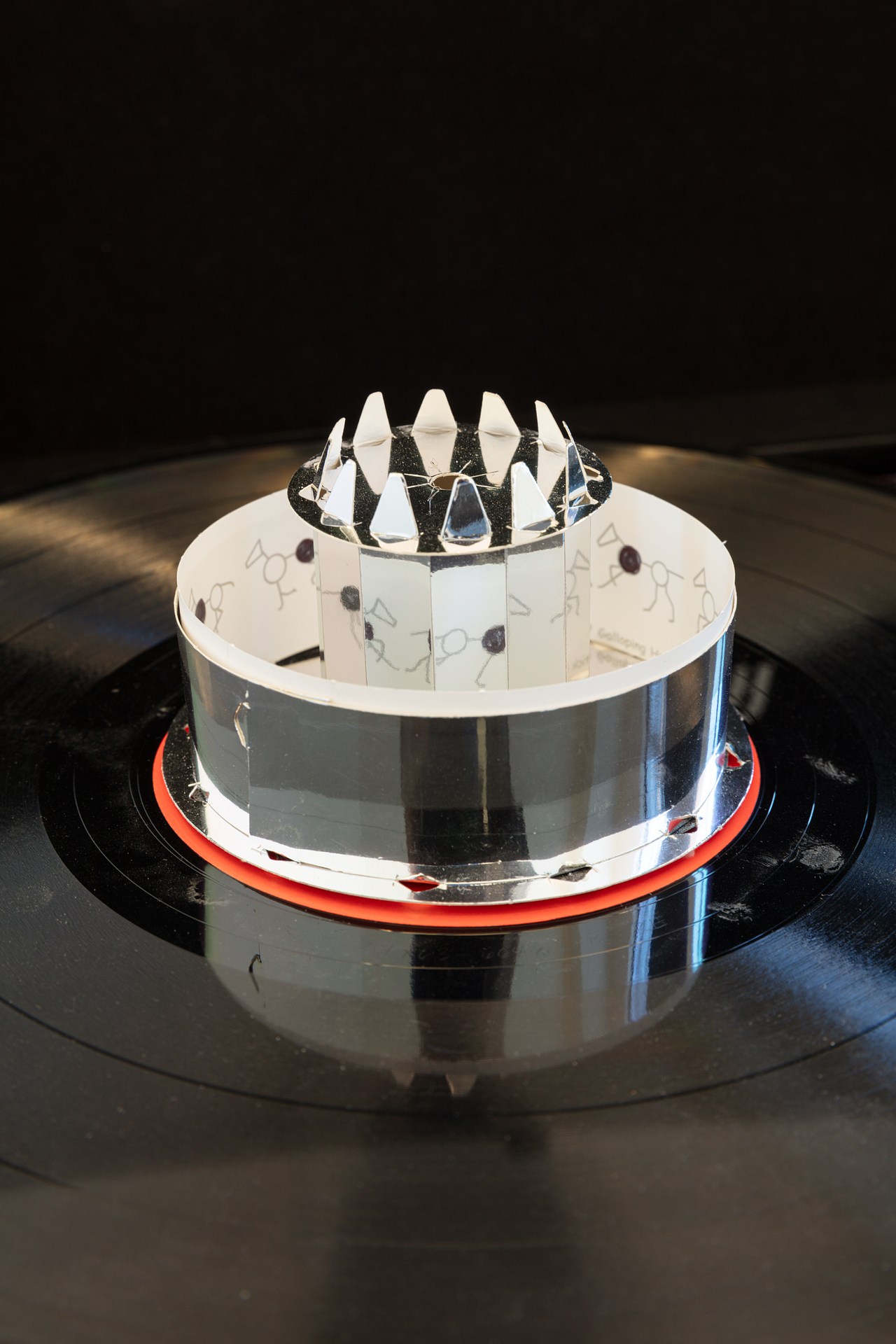

The show positions Cocteau as a brave forerunner for generations of queer artists who would follow. It opens with a piece not by Cocteau, but by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. The gesture, from curator and art historian Kenneth E. Silver, highlights Cocteau’s influence on younger generations (but only in this first room: the other works in this 150-plus-object show are by Cocteau or related ephemera). Made in 1991, the year that Ross Laycock, Gonzalez-Torres’s partner died, “Untitled” (Orpheus Twice) features two side-by-side full-length mirrors that recall the Orpheus myth—a long-standing motif in Cocteau’s work. While mourning and with his premature death looming, Gonzalez-Torres seemingly felt like Orpheus: separated from his lover, the twinned mirrors served as a kind of connection to Ross. Next to the mirrors, we see a clip from Cocteau’s 1950 film Orphée, which also uses that metaphor of the mirror as a portal—this time, one that takes the protagonist to Hades, where Orpheus seeks to save Eurydice.

Copyright

© Art News