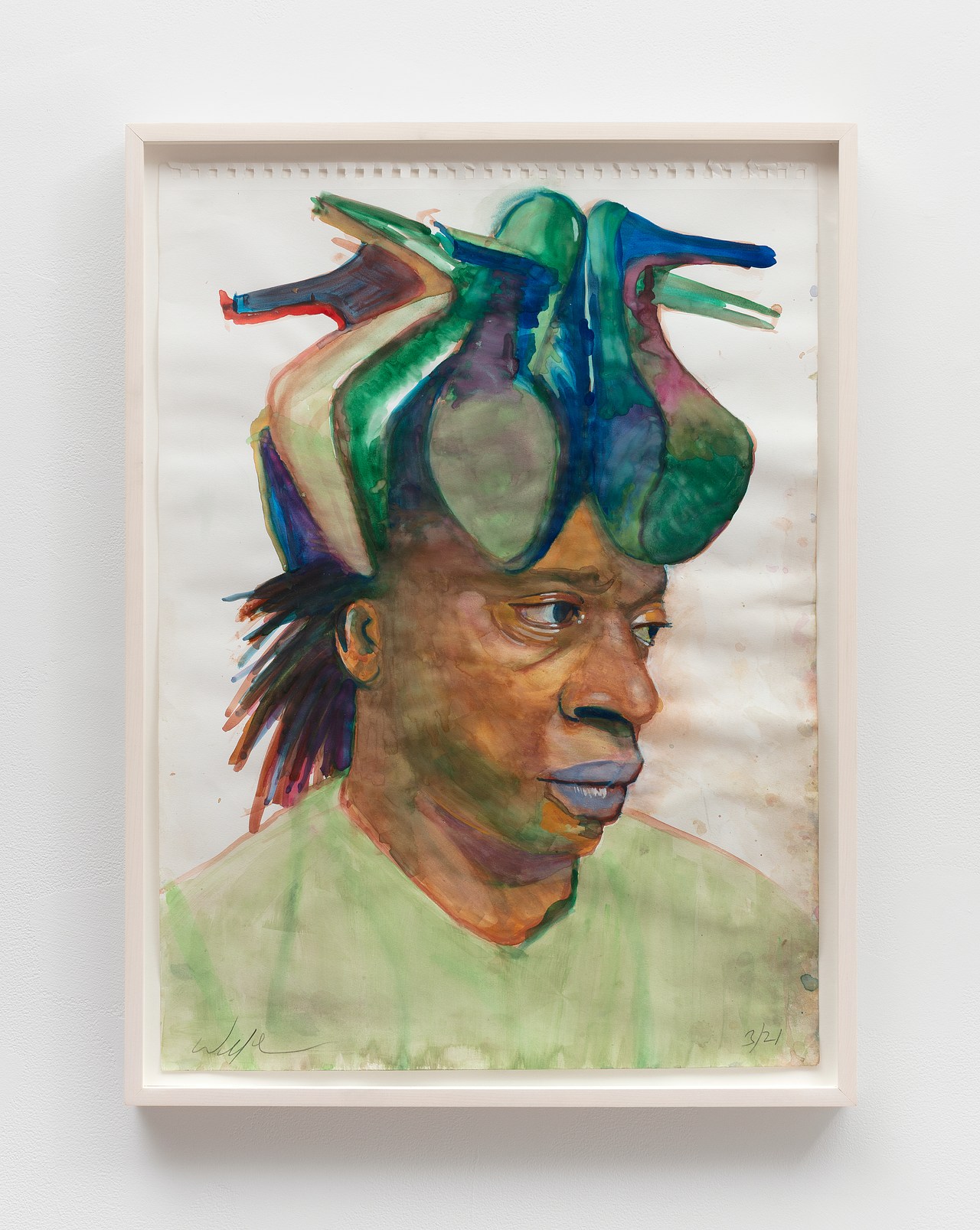

Lorenza Böttner gazes confidently and seductively over her left shoulder in a pastel self-portrait from 1989. Her hair is flowing; meanwhile, her naked and muscular body reflects the bands of rainbow light surrounding her. Though the environment lacks a horizon line, the rainbow fades into a deep, dark blue that helps ground the scene. Chalky, dirty footprints are scattered over the gradient, as if the paper had at one point itself been a ground—or more specifically, a dance floor. The portrait is a record of irreverent dancing in more ways than one: Böttner is grooving, and it’s contagious.

If you know anything about Böttner—a Chilean-German artist who was born in 1959, started presenting as female in art school, made many self-portraits, and died in her thirties of AIDS-related complications—you’ll recall that there is no arm at the end of that left shoulder she’s gazing over, nor at the end of her right one. Though it’s right there, in the middle of the five-foot sheet of paper, the nub on her shoulder is far from the first thing a viewer notices in this work. The other striking details include the deft, Degas-esque linework; the immaculate vibe; and Böttner’s skillful handling of color. The rainbow is both campy and delicate, gently refracted by the surfaces of her sculpted figure and windswept hair.

Lorenza Böttner, Untitled, 1985, pastel on paper, 51 by 63 inches.

All this the artist pulled off by drawing with her feet and her mouth. Yet rather than depict herself as a freak capable of feats, Böttner appears, in the 20 or so self-portraits on view in “Requiem for the Norm,” her retrospective at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York, engaged in various banal and tender acts: bottle-feeding a baby or reading a book as she turns the pages with her toes. The self-portraits don’t invite pity or applause, nor do they hide her disability. They are joyful and beautiful, and decidedly not about “overcoming.”

Spanning Böttner’s 16-year career, the show also highlights a few series of photo-based works as well as ephemera from performances, including footage, photographs, and posters. A video of her 1987 performance Venus de Milo, a landmark work of disability culture, shows Böttner covered in a fine layer of white plaster and standing on a platform with a cloth draped over her lower body. For more than 20 minutes, she holds a pose resembling that of the titular armless statue. Before descending the podium and exiting stage left, Böttner asks the audience, in German, “Well, what would you say if the artwork moves of its own accord?” This wry piece retools the politics of staring, calling attention to how impairment can seem downright romantic as a metaphor, or when depicted in art or suggested by ruins, while in daily life, visibly disabled people are often gawked at or shunned.