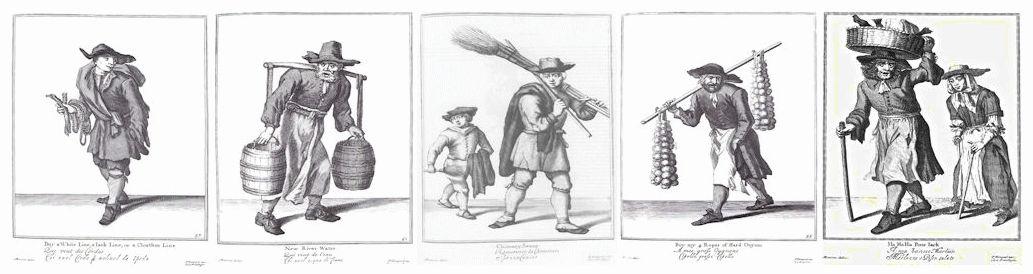

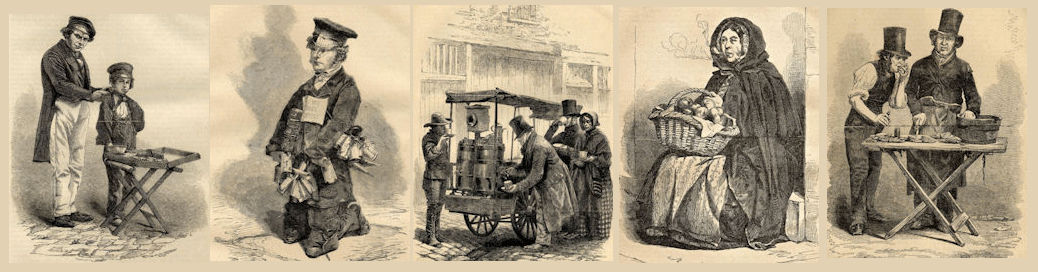

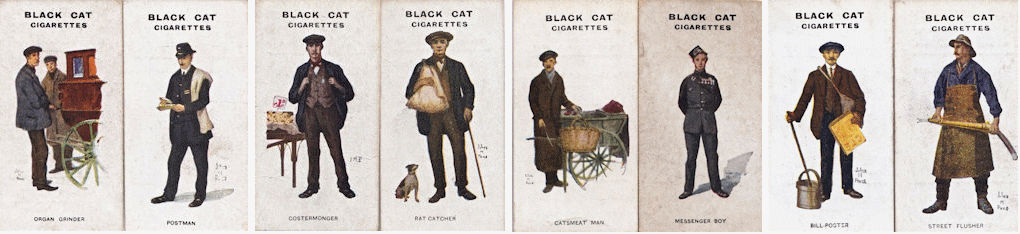

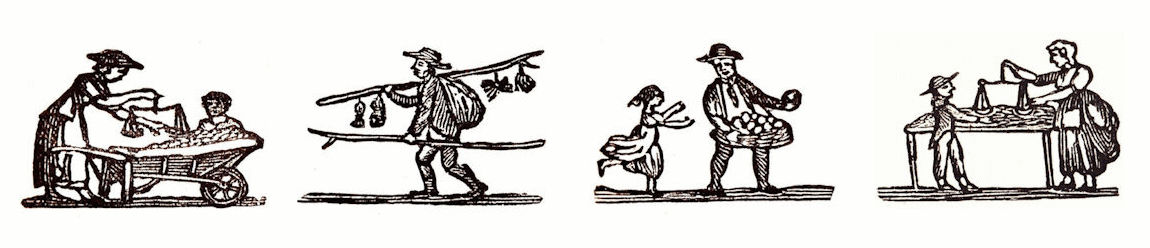

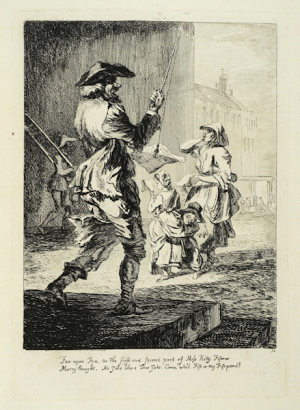

Street cries are the short, often lyrical calls of merchants/vendors hawking their products and services in city streets and open-air markets. The "Cries of London" was a re-occurring theme in English printmaking for over three centuries. These colourful prints form a visual record of London's "lower orders", the pedlars, charlatans, street hawkers, milkmaids, and grocers who made their living on the city streets. They give us a glimpse of a long forgotten London where tradesmen would advertise their wares with a musical shout or a melodic rhyme. Different versions of the "Cries" vary in tone from idealistic visions of happy street vendors to satirical caricatures. One of the most famous series of "London Cries" is the group of somewhat sentimental pictures executed by Francis Wheatley. Wheatley's series was immensely popular and enjoyed a long period of success in the English print shops. This popularity undoubtedly inspired Rowlandson to execute his satirical versions of the "Cries". In a set of eight prints, (number seven is missing and not recorded), Rowlandson created a group of witty images mimicking Wheatley's more earnest criers. Under his biting pen the "Cries" metamorphose into lascivious caricatures, Rowlandsonesque versions of London's street people.

According to Andrew Tuer, the earliest mention of street cries in London is found in an old ballad entitled " London Lyckpenny," or Lack penny, by John Lydgate, a Benedictine monk of Bury St. Edmunds, who flourished about the middle of the fifteenth century.

"Then unto London I dyd me hye,

Of all the land it beareth the pryse :

Hot pescodes, one began to crye,

Strabery rype, and cherryes in the ryse ; *(On the bough)

One bad me come nere and by some spyce,

Peper and safforne they gan me bede,

But for lack of money I myght not spede.

Then to the Chepe I began me drawne,

Where mutch people I saw for to stande ;

One spred me velvet, sylke, and lawne,

Another he taketh me by the hande,

' Here is Parys thred, the fynest in the land ; '

I never was used to such thyngs indede,

And wantyng money I myght not spede.

Then went I forth by London stone,

Throughout all Canwyke *(Candlewick) Streete ;

Drapers mutch cloth me offred anone,

Then comes me one cryed hot shepes feete ;

One cryde makerell, ryster* (Rushes green) grene, an other gan greete ;

On bad me by a hood to cover my head,

But for want of mony I myght not be sped.

Then I hyed me into Est-Chepe ;

One cryes rybbs of befe, and many a pye ;"

Two free ebooks, digitized by Google, by Tuer on London Cries are listed Here.

- Endeavor

- Category: London Street Cries

- 4692

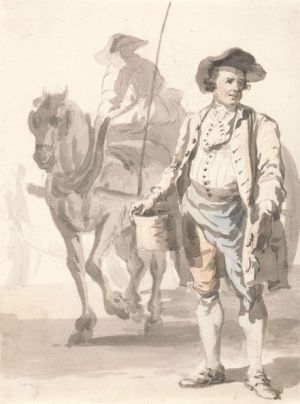

- Birth - Death: 1731 (Nottingham, England) - 7 November 1809 (London, England)

- Medium, style: English map-maker, etcher, landscape watercolorist

- Work: The Cries of London, "the father of modern landscape painting in watercolors", one of founders of the Royal Academy

- Wiki Link: Visit Website

Portrait of Paul Sandby - Francis Cotes - 1761 - Tate Britain, London, UK

This gallery presents a limited few of the one hundred or so drawings/sketches, and watercolors Sandby did of London's street traders, sellers, and hawkers in 1759. Many of these are taken from the Yale Center of British Art (Paul Mellon Collection). Links to the Yale Center, as well as additional links concerning Paul Sandby and his art, may be found in the main menu or, alternatively, HERE.

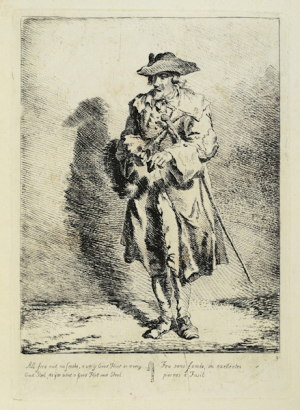

"Sandby's street drawings are the first in which the traders as portrayed as filthy and there is no doubt that the mackerel seller would have smelled foul too. Each of these sellers is a portrait of an individual, not just a social type as was the case in earlier series but, more than this, we have characters placed in a dramatic relationship to the world and, in many cases, stories that tell us of their circumstance.

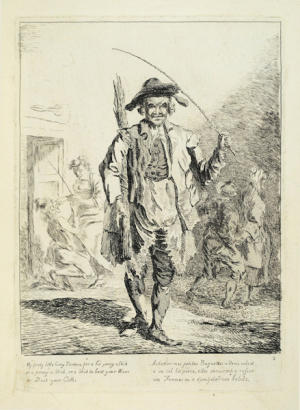

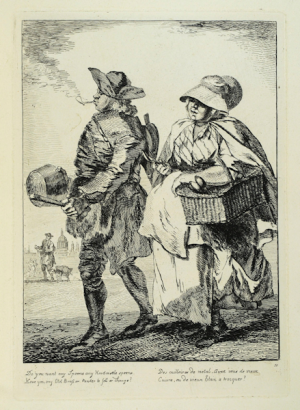

Far from merely picturesque, these hawkers confront us in ways that we might choose to avoid. The ballad seller proffering two parts of ‘Kitty Fisher’ was known to work with a pickpocket, while the seller of switches for the distribution of domestic punishment raises his arm as if he is about to lash out at us. The provocation offered by the low-bodiced woman offering nosegays and notebooks is overtly sexual, and her expectant posture turns the use of ‘Your honour’ into a challenge.

Yet the lack of sentiment does not ever reduce Paul’s subjects but, rather, grants them power and independent existence beyond his portrayal. No longer rendered as the amusing curiosities of earlier Cries, these hawkers are the first to demand our respect. While, in life, we might take detours or do almost anything to avoid them, these prints offer a more complex and troubling political relationship between sellers and buyers than had been described before".

The Gentle Author - Spitalsfield Life

In 1760, Paul Sandby moved to London from Winsor where he began to draw the underclass of street traders and hawkers with a new realism. In total, he made around a hundred drawings of the hawkers and vendors he encountered in the streets around his house in Carnaby Market. In that year, he had published Twelve London Cries Done from the life, Part 1st. These twelve were prints made from his etchings,engravings. These images are presented in this gallery. Although the title of this work suggests plans for additional prints he never published any more engravings from his watercolour sketches. He had already designed the title page for another series with the intention of turning all his sketches into prints, but the unsentimental quality of Sandby’s human observation rendered these Cries a disappointment in their time.

- Endeavor

- Category: London Street Cries

- 5224

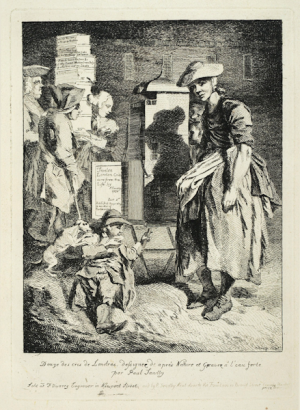

- Birth - Death: 1747 (Covent Garden, London, England) - 28 June 1801 (London, England)

- Medium, style: portrait and landscape painter

- Work: Portrait of a Sportsman with His Son, Soldier with Country Women Selling Ribbons, near a Military Camp

- Wiki Link: Visit Website

Oil Portrait thought to be Francis Wheatley - Unknown Artist (National Portrait Gallery, London, UK)

Oil Portrait thought to be Francis Wheatley - Unknown Artist (National Portrait Gallery, London, UK)

. . . In the midst of this turmoil, lacking aristocratic sitters, Wheatley created these images of street sellers which, although regarded in his lifetime as of little consequence besides his society portraits, are now the works upon which his reputation rests . . . However, these idealized images are far from social reportage . . . The languorous poise and artful drapery of Wheatley's figures suggest classical models, as if these hawkers were the urban equivalents of the swains and sheperdesses of the pastoral world. . . I like to surmise that these fine images celebrate the qualities of the people that Wheatley--like Laroon before him--experienced first-hand in the streets and markets, growing up in Covent Garden, and chose to witness in this affectionate and subtly-political set of pictures, existing in pertinent contrast to the portraits of rich patrons who shunned him when he was in need.

The Gentle Author's Cries! of London (p. 24)

Additional reference links about Wheatley and his art may be found in the main menu or HERE.

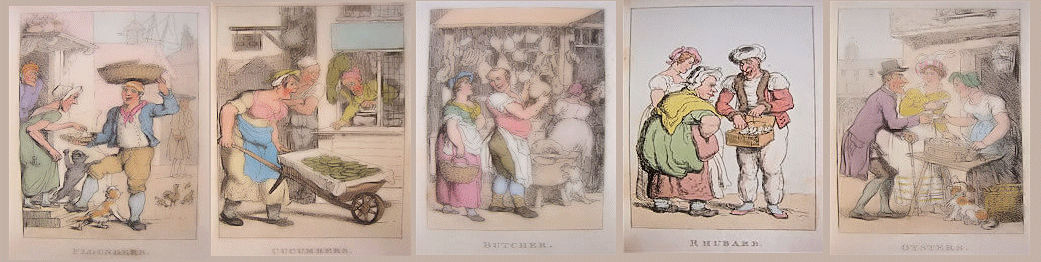

Francis Wheatley, 1747-1801, exhibited his series of oil paintings entitled the “Cries of London” at the Royal Academy (London) between 1792 and 1795. Wheatly was born in Covent Garden and grew up amongst the street hawkers and their cries. As such, he was well-suited to portray these street vendors.

Wheatley’s paintings of London street criers represent the century’s most successful depiction of London street criers, albeit also some of the most idealized. This may not be surprising given that they appeared at the Royal Academy from 1792 to 1795 when romantic and neoclassical aesthetics were at their zenith. A calm, clean, rosy-cheeked, business-like manner pervades.

In this regard, Wheatley's presentation my be contrasted with that of Marcellus Laroon’s “Cryes” (first published in 1687) and Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical Cries of London (which first appeared in 1799; later fifty-four plates in "Characteristic Sketches of the Lower Orders" in 1820).

In spite of the idealized presentation of Wheatley's paintings, it is important to note that Wheatley places working people at the center of the image and represents them with both an honest presence and an equal stature in labor. It is tempting to say that these are important human qualities that Wheatley found in the streets of London and did not find, after his election to the Royal Academy (at the expense of the King's nominee), among the British aristocracy.

Some additional information: